FIRST READING: Canada’s massive (and easily fixed) birth tourism problem

2023/06/03 Leave a comment

Second article in the National Post in a week. Hopper forgot to mention that the Conservative government did make a push to end birth tourism in 2012 (see my What the previous government learned about birth tourism):

Last week, Macleans’ published an interview with Simrit Brar, a Calgary OB-GYN who is one of Canada’s few medical researchers to actually look into the issue of birth tourism.

It’s something that’s long been an accepted fact within Canadian birthing hospitals: Hundreds of non-resident women each year are coming to Canada in the final weeks of pregnancy, having their baby in a Canadian hospital and then immediately returning home. The purpose of the excursion being to ensure that the child has Canadian citizenship by virtue of the country’s jus soli laws.

There are companies openly advertising their services as “birth hotels.” Online forums include questions as to the “cheapest” Canadian hospital for a non-resident to give birth. In the last full year before the COVID-19 pandemic, a single hospital in Richmond, B.C. had 502 non-resident births — nearly one quarter of total babies born.

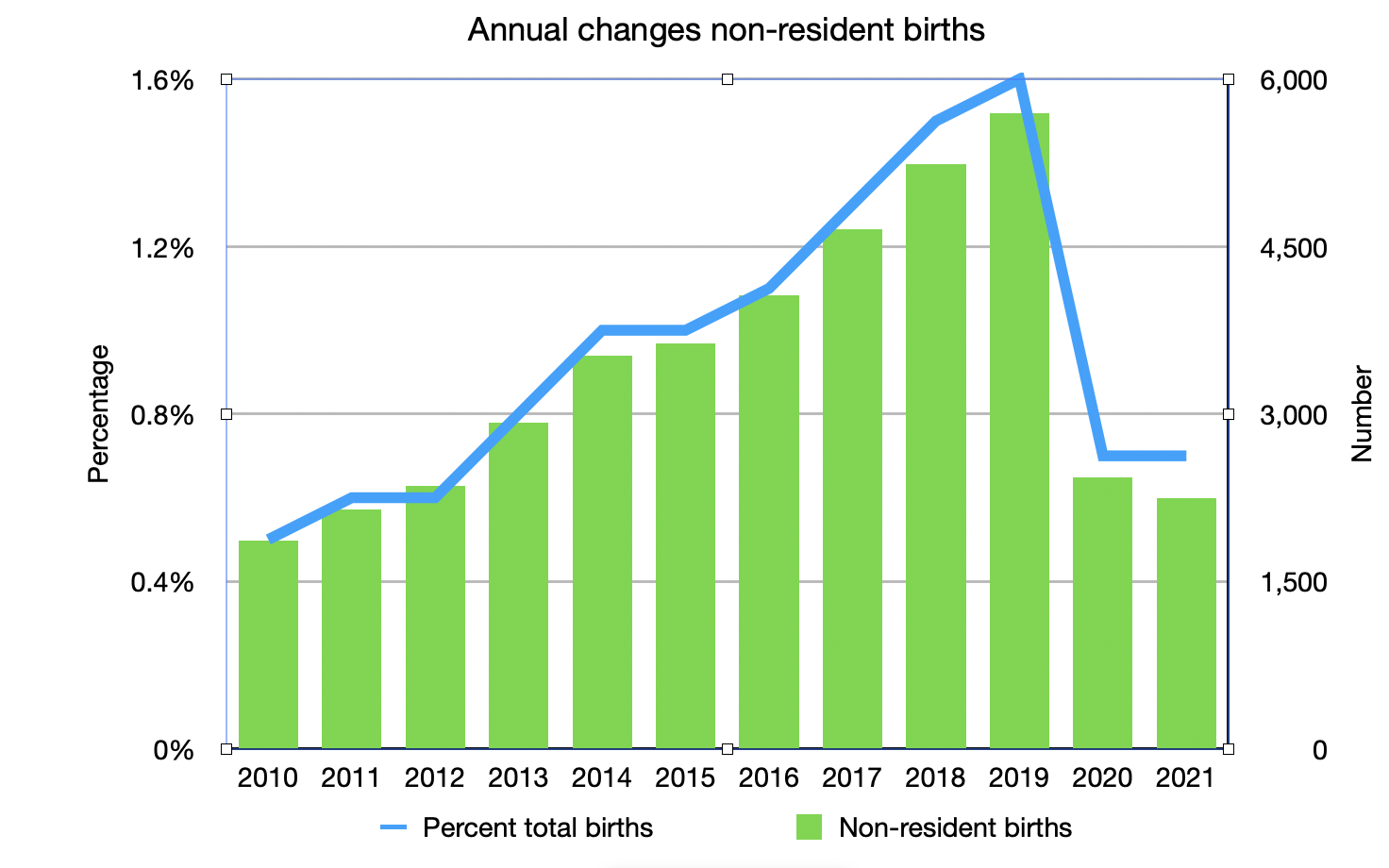

Figures from the Canadian Institute for Health Information show that Canada hosted a record 4,400 foreign births in 2019 — up from 1,354 just nine years prior.

Vancouver’s first baby of 2023, in fact, was born to a birth tourist: Mother Salma Gasser had only recently arrived from Cairo, Egypt, on her first-ever trip to Canada, and told local reporters she did it to secure a Canadian passport for her baby girl.

There’s nothing illegal about birth tourism and birth tourists are all paying handsomely for the service (it costs between $6,000 and $10,000 for an uninsured non-resident to give birth at a Canadian hospital). But for a Canadian health-care system that is constantly on the verge of crisis, the phenomenon is having an impact.

In a two-tier system like Australia, the U.K. or the U.S., an influx of non-residents seeking health-care beds could safely exist on the sidelines without affecting overall health-care access: The system could simply grow organically to accommodate the increased demand.

But Canada rations its supply of doctors and health-care workers, meaning that any extra patient is going to be adding to wait times.

“So even if a birth tourist does pay their bill, if we allow people who have the opportunity to pay to preferentially access beds … that displaces people here,” Brar told Maclean’s.

She added that birth tourism is a “social structure issue.” Ultimately, wealthy people from abroad are able to supplant scarce Canadian health-care resources, with negative results for “disadvantaged” Canadians.

“The system is too strained for us to ignore these questions,” she said.

Brar’s research examined 102 cases of birth tourists who had their babies in Calgary between July 2019 and November 2020. A plurality (24.5 per cent) were Nigerian and all told, the 102 paid $694,000 to Alberta Health Services in hospital fees.

Notably, most of Canada’s birth tourists are coming from countries that do not offer birthright citizenship. Almost all of North and South America grants automatic citizenship based on birthplace — a principle known as “jus soli,” or “right of the soil.”

In most of the rest of the world, citizenship is determined based on the nationality of one’s parents — known as “jus sanguinis,” or “right of the blood.” If a visiting tourist gave birth in Nigeria, for instance, that child would not be considered Nigerian unless they had a Nigerian parent or grandparent.

It would be remarkably easy for Canada to ban birth tourism, or at least make it less easy.

Provincial health-care systems could dramatically raise fees on “other country” birth services in order to discourage patients not insured under the Canadian system.

Some minor tweaks to the Citizenship Act could nullify instant citizenship if a baby is born to a parent temporarily visiting Canada on a tourist visa.

Refugees, asylum-seekers and other newcomers would still have guaranteed full, automatic citizenship for their Canadian-born children.

Or, Canada could simply begin denying visas to foreign nationals booking short trips to Canada at the tail end of a pregnancy. This is what the United States did in order to curb its own rising rates of birth tourism.

In early 2020, the U.S. Department of State issued an order to deny certain classes of recreational visas to foreign nationals if a consular official believed they were doing it just to give birth.

“The Department does not believe that visiting the United States for the primary purpose of obtaining U.S. citizenship for a child, by giving birth in the United States — an activity commonly referred to as “birth tourism” — is a legitimate activity for pleasure or of a recreational nature,” reads a statement from the time.

U.S. officials have also prosecuted California-based “birthing houses” for counselling foreign nationals to misrepresent their intentions on visa forms in order to enter the U.S. for the purpose of giving birth. Similar charges are feasibly possible in Canada, given that it is illegal under Canadian law to misrepresent one’s intentions for visiting.

Although birth tourism is not addressed or even acknowledged at the federal level, it’s long been deeply controversial in the immigrant-heavy Vancouver communities where it’s most visible.

Jas Johal, MLA for Richmond, has repeatedly denounced birth tourism for turning local hospitals into “passport mills.” Longtime Richmond city councillor Chak Au has often gone on record saying that his constituency — the most Chinese-Canadian in Canada — supports a legislated end to birth tourism.

In 2018, Richmond’s Liberal MP Joe Peschisolido tabled a petition in the House of Commons calling birth tourism an “abuse of Canada’s immigration and citizenship system.”

“The government should say birth tourism is bad. Let’s quantify it and let’s fix it,” he said at the time.

As recently as 2016, Vancouver-area Conservative MPs Alice Wong and Kenny Chiu even led a drive to overturn Canada’s system of birthright citizenship altogether in order to combat birth tourism — although both had reversed course by 2019, when the Conservatives prepared for that year’s election with a platform that mostly side-stepped immigration policy.

Source: FIRST READING: Canada’s massive (and easily fixed) birth tourism problem