Immigration is religion’s only hope – UnHerd

2023/09/21 Leave a comment

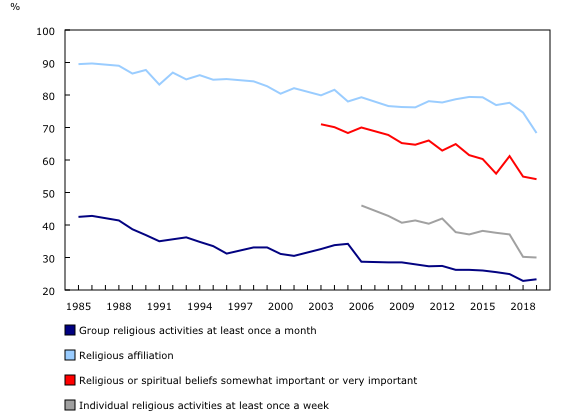

Of interest (similar trend in Canada):

When my father was going through the process of becoming an Elder in the United Methodist Church, he was required to take courses on Diversity, Equity and Inclusion. One course involved a presentation on how white people needed to make room for, and amplify the voices of, “people of colour”. My father is an immigrant from China. He, like other immigrant preachers, was confused about who the term “person of colour” referred to, and why a faith founded on the idea that there is “neither Jew nor Greek” is so obsessed with racial divisions.

Who can blame them? The progressive ideology that in recent years has swept through mainstream American Protestantism is often impenetrable to those from non-Western countries.

And yet, it is just such immigrants who are keeping Christianity alive in our secular world — everywhere from France’s Afro-Caribbean megachurches to London’s Black Majority Churches. In America, the number of citizens identifying as Christians has fallen from 90% to 64% in the last 50 years, while immigrants are becoming more influential: more than two thirds of them are Christians.American progressives are increasingly stoking fears of an incipient “white Christian nationalism” bringing about a Cromwellian theocracy. But white Americans have actually been secularising at a slightly faster rate than other ethnicities. While black Americans have also experienced secularisation, they are still more likely to go to church and pray than the average American. And African immigrants to the US are more religious than American-born black people. The rise of Latino evangelicals in America has also been receiving mainstream coverage.“Conservative Christians”, the bogeyman for white progressives, are therefore increasingly likely to be people of colour — the very people whose voices progressives apparently want to amplify. Christians of African origin are far more likely to hold conservative views on sexuality, while Latino evangelicals are quickly becoming a Republican bloc.

White conservatives, meanwhile, have a tendency to bemoan the secularisation of the West and the decline of traditional values, while supporting restrictive immigration processes — perhaps not realising that non-Western immigrants are more likely to be socially conservative than American-born citizens, or perhaps because their economic or tribal instincts trump their religious ones. Both progressives and conservatives are therefore mired in contradiction.

Despite the fact that liberals are secularising faster than conservatives, for the last decade, the leadership of the United Methodist Church has been adopting views on sexuality and gender identity that are in line with those of secular progressives, triggering a slow-motion denominational schism. Some years ago, I attended a UMC conference with my parents at which some attendees wore rainbow armbands in support of a movement to ordain gay clergy. Almost all of them were white. None of the representatives from immigrant congregations, and few from black congregations, wore the armbands. “Before I came to America, I thought this was a nation built on Christian values,” commented one attendee. “Why are these people going against God’s will?”

A progressive Christian might see this as a contradiction: if Jesus came from Heaven to help the marginalised, why do these marginalised Christians antagonise a fellow marginalised group? Liberal white people, who usually preach multicultural ideals, cannot answer this question honestly without making it sound like Western culture has the “correct” view on sexuality — the major irony being that progressives dismiss Western culture for what they see as regressive views.

While progressives blame “the Christian Right” for society’s ills, religious conservatives often complain about “woke Christianity”. They point to examplessuch as Allendale United Methodist Church, which had a “non-binary” drag queen deliver sermons and bills itself as “a church that is committed to anti-racism and radical solidarity with folx on the margins”. They argue that such acts are based on ideology stemming from the secular world rather than theology based on Biblical exegesis.

A similar dynamic can be observed in the UK. Earlier this year, the Church of England floated the idea of using gender-neutral pronouns for God, and allowed prayers of blessing for gay couples. The backlash was swift. Many bishops in Africa and Asia rejected the authority of the Archbishop of Canterbury — and criticised the Anglican church’s (largely white) leadership. But even within the UK, there was fierce opposition to progressive Christianity from ethnic minorities, who are keepingBritain’s Christian population from declining.

However, the religious conservatives probably have less to worry about than the progressives, in the long run. If progressive Christian churches align themselves more closely to the values of secular society than to religious ones, they will cease to exist. A similar phenomenon can be seen in American Judaism. Orthodox Jews, who take their faith seriously, and mostly vote Republican, are currently in the minority, but they are estimated to grow to become the dominant branch of American Judaism by 2050. This is partly due to birth rates, but also because non-Orthodox Jews, who mostly vote Democrat, are secularising quickly; they are far more likely to partner with non-Jews, stop observing Jewish traditions, or to cease to identify as Jewish altogether. Christianity, too, looks set to depend on the most orthodox sustaining the faith.

It is ironic that Christianity is now seen as “problematic” by progressives, because the roots of liberalism, which opened the door for progressivism, partially derive from Christianity — or Protestantism, to be specific. It was the Reformation that shifted religious practices away from a central authority to that of individuals. As Tom Holland has pointed out, almost every country that has legalised gay marriage has been shaped by centuries of both liberalism and Protestantism.

It is also ironic that white progressives support multiculturalism over assimilation, because it is the latter that would align the beliefs of immigrant communities with the values of the utopia dreamed of in Diversity, Equity and Inclusion trainings. In other words, though liberalism paved the way for immigration and multiculturalism, immigration and multiculturalism actually weaken liberalism; though Christianity paved the way for liberalism, Christianity could prove liberalism’s downfall.

The tension between a multicultural utopia pushed by secular progressives versus the socially conservative, religious-inflected attitudes many non-white groups hold has led to quite a few awkward skirmishes. While most black people vote for the same party as white liberals, 37% of black Democrats say their religious views influence how they think about transgender topics, compared to only 11% of white Democrats. While 66% of black Democrats say a person’s gender is their sex determined at birth, only 27% of white Democrats say the same.

Conservatives in America are also tying themselves in strange knots. A common refrain is that Islam is incompatible with Western civilisation. And yet, some conservative Christians find themselves allied with Muslims against what they both see as America’s decadent hyper-individualistic secular culture. In a number of American cities, Muslims have joined conservative Christiansto protest the inclusion of explicitly LGBT-themed books in elementary schools, leading to accusations that “some Muslim families” are “on the same side of an issue as White supremacists and outright bigots”. To progressives, a “bigot” is a stereotypical white Christian conservative; to see non-white Muslim families standing beside them in droves caught many off guard. An all-Muslim city council in Michigan was once held up by liberals as a symbol of diversity, until it voted earlier this year to ban Pride flags being flown on city property, to the delight of many social conservatives. Slate has gone so far as to call Muslim voters “the new Republicans” — an unexpected twist after two decades of Republican fear-mongering against Islam.

At the same time, presidential candidate Vivek Ramaswamy, a Hindu, has gone from a virtual unknown to third place in the Republican primary, by picking up the support of many conservative Christian voters. Ramaswamy does not shy away from his faith, but rather emphasises the similarities between certain schools of Hindu and Christian thought. Many conservative Christians, it seems, would rather ally with conservatives from other religions than Christians on the other side of the political divide.

It has taken a cosmic convergence of contradictions to get to this point. White progressives, with their absolute devotion to immigration, have inadvertently championed immigrants from cultures that outrightly reject progressivism. With their just-as-absolute devotion to multiculturalism, those same white progressives have created a trap for themselves where they are unable to criticise a non-white person’s culture, values or beliefs — even when they actively go against sacred progressive views on gender and sexuality. Meanwhile, white conservatives find themselves forging alliances with people they never thought they’d work with — people whose entry into the country they might have objected to. Old alliances are dissolving — and battle lines are drawn anew.