Good long read on the university and college cash cow and a program that has increasingly deviated from an education to a labour program, with some interesting insights from Australia.

While bit over the top, this money quote has an inconvenient truth:

“The whole objective of international education is just to make money and to grow the economy. It has really little to do with education,” says Kahlon. “If we’re honest about what the international education strategy is, it is just to raise Canada’s GDP.”

—

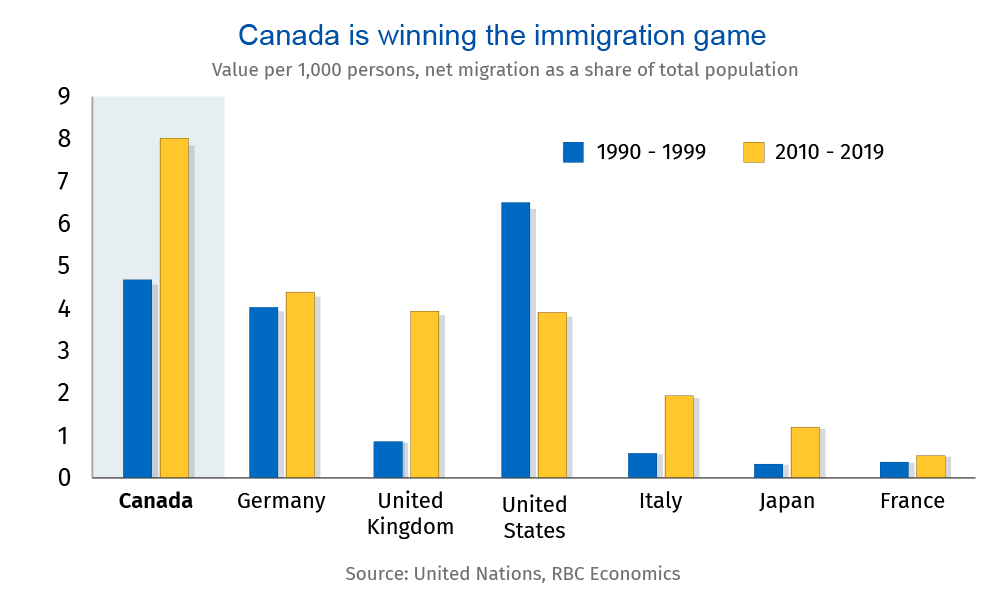

Canada’s international education strategy has been an undisputable success — the envy of other nations — attracting foreign students to come and study with the promise of work opportunities and the prospect of permanent residency and citizenship.

Over the years, the campaign has injected billions into the economy, created a pipeline of immigrants and fuelled a post-secondary education sector that struggled with declining public funding and falling domestic enrolment.

But that successful formula and unfettered growth seems to have reached a tipping point.

Students who are falling through the cracks are starting to question whether their investment of time and money, by way of hefty tuition fees, is paying off.

And Canada doesn’t need a crystal ball to see what lies ahead.

“A CASH cow is all very well, and a fine thing when it is happily chomping in the field. But what happens when it grows horns, turns nasty and demands that you feed it more and look after it better?”

That was a question raised in an article published in The Age, one of Australia’s oldest and most reputable newspapers, back in 2008. At the time, Australia was seeing an exponential growth in international enrolment that made the then-$12.5 billion international education sector its third-largest export after coal and iron.

“There is pressure on the industry from without and within. Increasing competition from foreign universities in the global race for market share, Australian universities at capacity, and a growing perception that Australia’s international students have been exploited on one hand, and neglected on the other, are biting hard,” the story continued.

There were other reports about international students in Australia being “underpaid and exploited” as a labour underclass, of students struggling with social isolation, feeling unhappy with the immigration prospects and facing “severe overcrowding” in rooming houses, including one extreme case where 48 students were living in a six-bedroom property.

Canada has been following a similar trajectory, some say.

The pandemic has further exposed international students’ precariousness and our country’s disjointed education and immigration systems, which leave students disillusioned amid a patchwork of support that relies on the goodwill of the schools, employers and local communities.

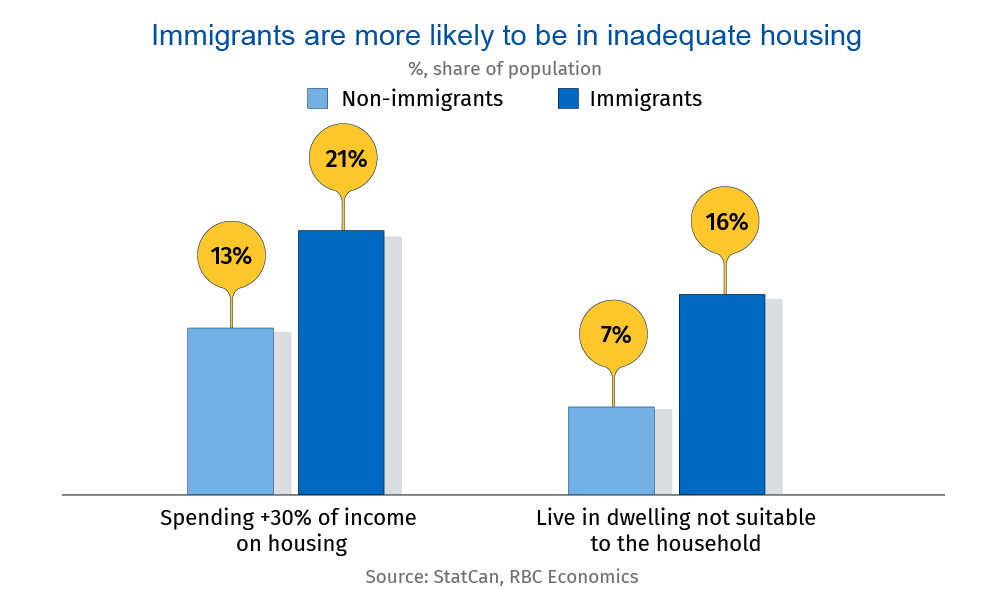

More and more international students in Canada are publicly complaining about exploitation and wage thefts by bad employers and landlords, the financial and emotional hardship of the journey, and the unfulfilled immigration dream sold to them by unscrupulous education recruiters.

Increasingly, there’s a recognition that what they have been promised is not exactly what they’re getting. while studying in Canada is not a guaranteed pathway for permanent residence that many expect.

It’s led to a growing chorus of voices calling on the Canadian government to refresh its strategy to ensure its international enrolment growth is sustainable and its appeal as a destination of choice will last.

But what would a reset, recalibrated international student program look like in Canada?

There is some no shortage of possibilities.

Resetting Canada’s international education strategy

The Canadian government launched an aggressive campaign in 2014 to boost its annual number of international students to more than 450,000 by 2022.

The country has long surpassed that goal.

Last year, there were 845,930 valid study permit holders in Canada, which rose to 917,445 as of Sept. 30 of this year.

International students, through their spending and tuition, contribute $22 billion to the Canadian economy and support 170,000 jobs in the country.

Those international students, who typically pay up to four times more in tuition than their domestic counterparts, are a godsend to many Canadian colleges and universities to help fill classroom seats and keep courses open for domestic students who otherwise would’ve had fewer options from which to choose. They are also embraced by employers desperate for temporary help at gas stations, restaurants and factories to keep businesses running.

Yet there have been increasing public calls for the federal government to better align academic goals, Canada’s economic needs and the interests of students.

The RBC has recently recommended Ottawa to be more strategic in leveraging and expanding its international student pool in the global race for skilled workers post-pandemic; the Conference Board of Canada in a separate report urged better co-ordination to ensure the number of international students admitted are in line with thelevel of permanent residents admitted each year to avoid further “friction.”

Australia moved to reset its own system.

International enrolment there had blossomed from 256,553 in 2002 to 583,483 in 2009 as migrants were drawn by the opportunities to work and stay in the country permanently before Canberra decided to rein in an unruly sector by “desegregating education and immigration.”

Australian officials began asking education institutions to register international education agents who worked for them and to review their performances based on student enrolment outcomes.

The bar for permanent residence was raised and limited to those who completed degree-level programs, postgraduate programs and regulated professions such as nursing, engineering and social work.

All applicants must submit a statement detailing their personal circumstances and why they pursue a particular program in Australia. Each is assessed based on the study plan, as well as factors such as the economic situation, military service commitments and even political and civil unrest in the person’s home country to make sure they are “genuine temporary entrants.”

Today, international education is still worth about $34 billion (Canadian) to Australia’s economy, with 418,168 in higher education out of 882,482 students in international enrolment in 2020. The rest were mainly in language training and vocational schools.

International students, meanwhile, go where the opportunities are. Experts say students traditionally turn to other jurisdictions with fewer perceived barriers when countries such as Australia restrict the pipeline.

Students “are using commercial agents to find the cheapest, most affordable routes there are,” says Chris Ziguras, a professor at RMIT University in Melbourne, who studies the globalization of education.

“At the moment, I think there’s a lot of students clearly voting with their feet and choosing that pathway into Canada over other pathways which are more expensive, more difficult and more restrictive. And that’s why we’re seeing the bulge there.”

A patchwork of settlement supports for foreign students

Noor Azrieh didn’t know anyone in Canada when she came to Carleton University in 2018 for a four-year journalism and human rights program. The 22-year-old Lebanese says she has had issues finding housing and skilled jobs because of her temporary status.

Landlords would often ask for six-to-eight-month rent deposits and demand a Canadian guarantor, while employers lost interest in hiring her once they found out she was here on a time-limited post-graduate work permit.

“It feels like you are doing this entirely alone. And maybe that’s just how it is,” says Azrieh, who works full time as an associate producer at CANADALAND. “Maybe I wasn’t ready to move across the country, across the globe, to a country that I didn’t know. But it felt like I was doing everything alone.”

.Colleges and universities are educational institutions, and some don’t have the capacity to properly support international students, who lack access to the kind of settlement services designed exclusively for permanent residents.

In light of the service gaps, immigrant agencies in B.C. now provide support for international students and temporary foreign workers through one-on-one information and referral, workshops and support groups.

Nova Scotia also launched a pilot program recently that offers international students in their final year help with career development opportunities and community connections to successfully transition to permanent residence.

However, these supports are piecemeal and it’s unclear who is responsible for the costs and the students’ well-being, says Lisa Brunner, a University of British Columbia doctoral student, whose research focuses on immigration, higher education and internationalization.

“If you’re coming from an institution’s perspective, my goal is to support students in their education and their experience in Canada, versus the government saying, ‘OK, we want to support this person because they’re a future immigrant and we want to retain them,’ ” she says.

“Those are two different types of services.

“The way it’s structured now works well for the government, because essentially the students themselves are responsible for the settlement process. Either they acquire the capital that’s necessary to succeed in the labour market to qualify for permanent residence or they don’t. In this way, the government doesn’t have to fund the services.”

“We all acknowledge giving access to students to those (settlement and support) services from the beginning of their journeys would be a tremendous return on investment for Canada,” says Larissa Bezo, president and CEO of the Canadian Bureau for International Education, a not-for-profit organization that aims to promote and advance Canadian international education.

“There’s a shared responsibility that we have … And in a federation like ours, that’s complex. I’m under no illusion. But we need to do a better job of connecting these dots.”

Coming out of the pandemic, Bezo says, Canada’s global brand has remained strong as Canadian governments and the sector pivoted in supporting international students through the crisis as other countries such as Australia asked their students to go home.

Clear messaging to international students

Balraj Kahlon, who co-founded One Voice Canada in British Columbia in 2019 to support and advocate for international students, says Canada’s international education strategy has been “ruthlessly” successful.

“The whole objective of international education is just to make money and to grow the economy. It has really little to do with education,” says Kahlon. “If we’re honest about what the international education strategy is, it is just to raise Canada’s GDP.”

He says the country’s international enrolment has increasingly been coming from the working poor in developing countries, lured by Canada’s relatively low tuition fees, the chance to work and make money to pay off family loans for the studies, and sometimes misinformation by unscrupulous education agents about the direct pathway for permanent residence.

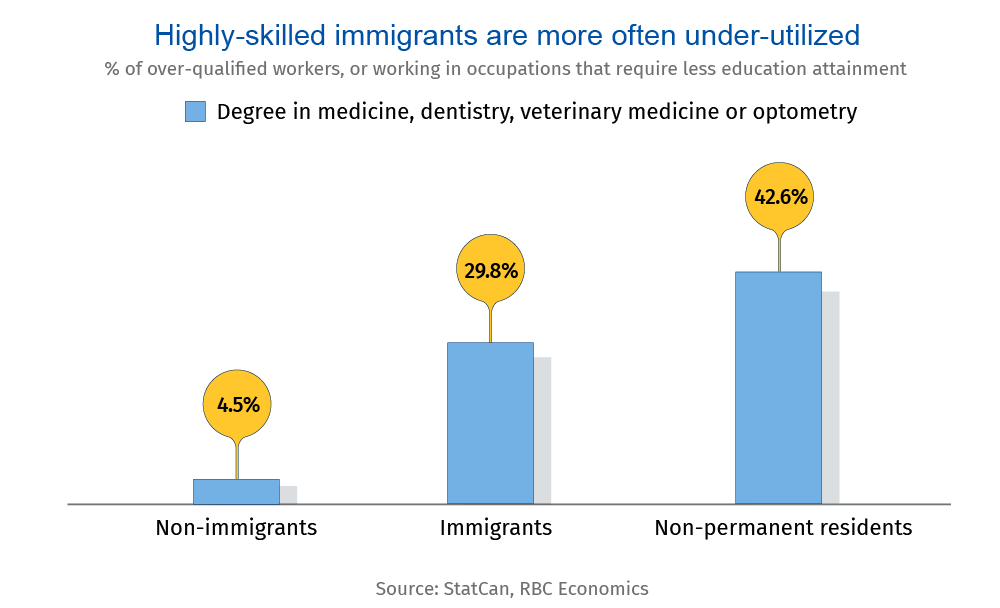

He says many international students these days are pursuing the cheaper and shorter programs at colleges with the sole intent of immigration, even if they know they can’t afford the tuition fees and their courses won’t get them beyond a warehouse, factory or retail job.

Yet, he says many can’t resist the allure of the opportunity for permanent residence and a life toiling in low-wage, low-skilled jobs in Canada that still pay more than what they would earn back home.

If the international education strategy really aims to attract the best and the brightest, he says, permanent residency should be limited to the students who are at the top in their fields by lowering their tuition and making schooling affordable to them.

“Until you get rid of the profit motive, problems are going to keep coming, because the incentive is always just more numbers,” says Kahlon.

Sixty per cent of international students do plan to apply for permanent residence in Canada, but only three in 10 international students who entered the country in 2000 or later ended up obtaining permanent residence within 10 years.

While some fail to complete their education or secure employment for immigration, others find opportunities elsewhere and leave.

“Higher-education admission policies and procedures have a very different goal than the admission criteria for economic immigrants,” says Grunner, the UBC researcher. “That difference is not always clear to students before they come to Canada.

“The message they get is that Canada wants international students. That’s the policy message that gets communicated. International students are desired by Canada for their labour. We got that message very clear because it says that international students can now work for the next year with unlimited hours. And international students are desired as potential immigrants.”

Diversifying where and what students choose to study

Paul Davidson, president of Universities Canada, says there is capacity to absorb more international students, though that capacity isn’t evenly distributed across the country.

Governments, education institutions, immigrant settlement agencies, local communities and employers all have a stake in ensuring international students’ experience and well-being, he says.

“It’s really important that international students get credible information and are supported in every step of their training,” says Davidson, whose organization is the voice for 93 Canadian universities. “There are people making false claims about what their experience in Canada will be and we need to call that out.”

Denise Amyot, his counterpart at Colleges and Institutes Canada, says the federal government not only needs to diversify the source of international students here (currently 35 per cent from India; 17 per cent from China; and four per cent from France), but also where and what they choose to study.

Her organization released a report last year, calling for new permanent residency streams and supports for colleges to improve their labour market outcomes.

“I would be in favour of accelerating permanent residency for students that are in the areas of skills that we need,” says Amyot, who also would like to see international students be eligible for government-funded co-op and job programs.

“It’s important that students do their homework (and ask), ‘How I will be integrated into the community,’ where they look at the best possible scenario for what they want to do and what’s their intentions moving forward.”

Global Affairs Canada says the government has aimed to diversify the countries of origin of its international students, promote study opportunities, especially outside of major urban centres, and showcase sectors to highlight areas of labour shortages and encourage study in those fields through digital marketing initiatives.

Several targeted international ad campaigns will be carried out to promote programs in STEM, artificial intelligence and quantum technologies, the department says. Consultations are underway to renew the country’s international education strategy.

Striking a balance

Sana Banu, an international student from India, can’t say enough about the amazing experience she’s had at Kitchener, Ont.-based Conestoga College, despite all the challenges her peers face and a pathway to permanent residence that’s full of pitfalls.

It has given her experience that has pushed her out of her comfort zone, says the 29-year-old, who came here in 2018 to study marketing and communication with an undergrad degree and eight years of work experience in advertising back home.

International students are a diverse group, each with their expectations and intentions, and it’s impossible to generalize everyone’s experience.

To Banu, the issues come down to equity — whether it’s about the hefty and uncapped international tuition fees or job opportunities that usually favour permanent residents and citizens.

“The relationship shouldn’t be predatory,” says Banu, president and CEO of Conestoga’s student association, who was recently invited to apply for permanent residence. “It’s a mutually beneficial relationship that international students provide to Canada and Canada provides to international students.

“It’s important that everybody sees the human side of an international student rather than just as a resource to fill your economic gaps and contribute to your economy exclusively. They are humans, who are coming here with expectations, dreams and hopes. And you could do a lot more in treating them with more dignity, equity and compassion.”

Source: How Canada can fix its ‘predatory’ relationship with international students

Canada’s international education strategy has been an undisputable success — the envy of other nations — attracting foreign students to come and study with the promise of work opportunities and the prospect of permanent residency and citizenship.

Over the years, the campaign has injected billions into the economy, created a pipeline of immigrants and fuelled a post-secondary education sector that struggled with declining public funding and falling domestic enrolment.

But that successful formula and unfettered growth seems to have reached a tipping point.

Students who are falling through the cracks are starting to question whether their investment of time and money, by way of hefty tuition fees, is paying off.

And Canada doesn’t need a crystal ball to see what lies ahead.

“A CASH cow is all very well, and a fine thing when it is happily chomping in the field. But what happens when it grows horns, turns nasty and demands that you feed it more and look after it better?”

That was a question raised in an article published in The Age, one of Australia’s oldest and most reputable newspapers, back in 2008. At the time, Australia was seeing an exponential growth in international enrolment that made the then-$12.5 billion international education sector its third-largest export after coal and iron.

“There is pressure on the industry from without and within. Increasing competition from foreign universities in the global race for market share, Australian universities at capacity, and a growing perception that Australia’s international students have been exploited on one hand, and neglected on the other, are biting hard,” the story continued.

There were other reports about international students in Australia being “underpaid and exploited” as a labour underclass, of students struggling with social isolation, feeling unhappy with the immigration prospects and facing “severe overcrowding” in rooming houses, including one extreme case where 48 students were living in a six-bedroom property.

Canada has been following a similar trajectory, some say.

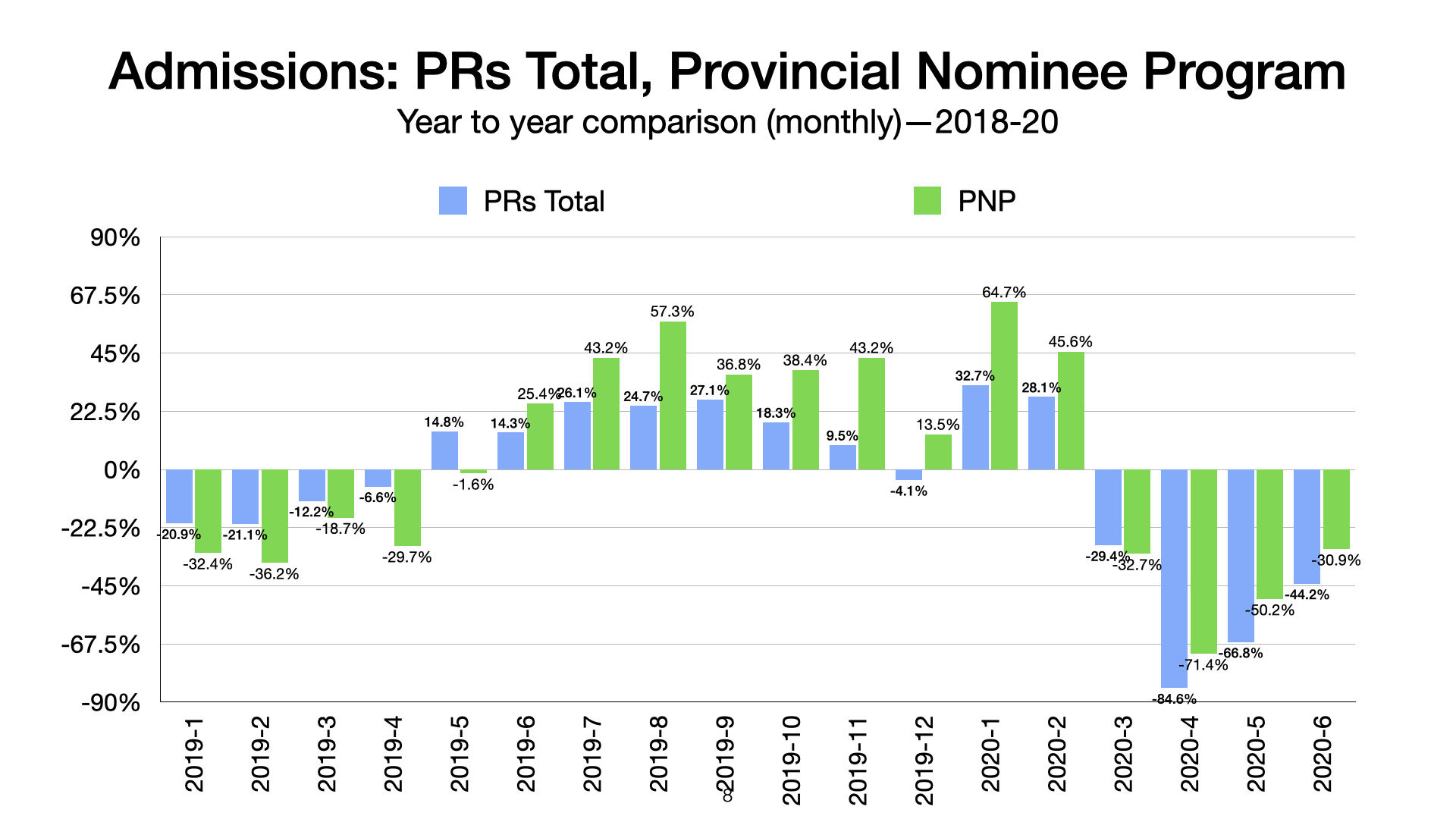

The pandemic has further exposed international students’ precariousness and our country’s disjointed education and immigration systems, which leave students disillusioned amid a patchwork of support that relies on the goodwill of the schools, employers and local communities.

More and more international students in Canada are publicly complaining about exploitation and wage thefts by bad employers and landlords, the financial and emotional hardship of the journey, and the unfulfilled immigration dream sold to them by unscrupulous education recruiters.

Increasingly, there’s a recognition that what they have been promised is not exactly what they’re getting. while studying in Canada is not a guaranteed pathway for permanent residence that many expect.

It’s led to a growing chorus of voices calling on the Canadian government to refresh its strategy to ensure its international enrolment growth is sustainable and its appeal as a destination of choice will last.

But what would a reset, recalibrated international student program look like in Canada?

There is some no shortage of possibilities.

Resetting Canada’s international education strategy

The Canadian government launched an aggressive campaign in 2014 to boost its annual number of international students to more than 450,000 by 2022.

The country has long surpassed that goal.

Last year, there were 845,930 valid study permit holders in Canada, which rose to 917,445 as of Sept. 30 of this year.

International students, through their spending and tuition, contribute $22 billion to the Canadian economy and support 170,000 jobs in the country.

Those international students, who typically pay up to four times more in tuition than their domestic counterparts, are a godsend to many Canadian colleges and universities to help fill classroom seats and keep courses open for domestic students who otherwise would’ve had fewer options from which to choose. They are also embraced by employers desperate for temporary help at gas stations, restaurants and factories to keep businesses running.

Yet there have been increasing public calls for the federal government to better align academic goals, Canada’s economic needs and the interests of students.

The RBC has recently recommended Ottawa to be more strategic in leveraging and expanding its international student pool in the global race for skilled workers post-pandemic; the Conference Board of Canada in a separate report urged better co-ordination to ensure the number of international students admitted are in line with thelevel of permanent residents admitted each year to avoid further “friction.”

Australia moved to reset its own system.

International enrolment there had blossomed from 256,553 in 2002 to 583,483 in 2009 as migrants were drawn by the opportunities to work and stay in the country permanently before Canberra decided to rein in an unruly sector by “desegregating education and immigration.”

Australian officials began asking education institutions to register international education agents who worked for them and to review their performances based on student enrolment outcomes.

The bar for permanent residence was raised and limited to those who completed degree-level programs, postgraduate programs and regulated professions such as nursing, engineering and social work.

All applicants must submit a statement detailing their personal circumstances and why they pursue a particular program in Australia. Each is assessed based on the study plan, as well as factors such as the economic situation, military service commitments and even political and civil unrest in the person’s home country to make sure they are “genuine temporary entrants.”

Today, international education is still worth about $34 billion (Canadian) to Australia’s economy, with 418,168 in higher education out of 882,482 students in international enrolment in 2020. The rest were mainly in language training and vocational schools.

International students, meanwhile, go where the opportunities are. Experts say students traditionally turn to other jurisdictions with fewer perceived barriers when countries such as Australia restrict the pipeline.

Students “are using commercial agents to find the cheapest, most affordable routes there are,” says Chris Ziguras, a professor at RMIT University in Melbourne, who studies the globalization of education.

“At the moment, I think there’s a lot of students clearly voting with their feet and choosing that pathway into Canada over other pathways which are more expensive, more difficult and more restrictive. And that’s why we’re seeing the bulge there.”

A patchwork of settlement supports for foreign students

Noor Azrieh didn’t know anyone in Canada when she came to Carleton University in 2018 for a four-year journalism and human rights program. The 22-year-old Lebanese says she has had issues finding housing and skilled jobs because of her temporary status.

Landlords would often ask for six-to-eight-month rent deposits and demand a Canadian guarantor, while employers lost interest in hiring her once they found out she was here on a time-limited post-graduate work permit.

“It feels like you are doing this entirely alone. And maybe that’s just how it is,” says Azrieh, who works full time as an associate producer at CANADALAND. “Maybe I wasn’t ready to move across the country, across the globe, to a country that I didn’t know. But it felt like I was doing everything alone.”

.Colleges and universities are educational institutions, and some don’t have the capacity to properly support international students, who lack access to the kind of settlement services designed exclusively for permanent residents.

In light of the service gaps, immigrant agencies in B.C. now provide support for international students and temporary foreign workers through one-on-one information and referral, workshops and support groups.

Nova Scotia also launched a pilot program recently that offers international students in their final year help with career development opportunities and community connections to successfully transition to permanent residence.

However, these supports are piecemeal and it’s unclear who is responsible for the costs and the students’ well-being, says Lisa Brunner, a University of British Columbia doctoral student, whose research focuses on immigration, higher education and internationalization.

“If you’re coming from an institution’s perspective, my goal is to support students in their education and their experience in Canada, versus the government saying, ‘OK, we want to support this person because they’re a future immigrant and we want to retain them,’ ” she says.

“Those are two different types of services.

“The way it’s structured now works well for the government, because essentially the students themselves are responsible for the settlement process. Either they acquire the capital that’s necessary to succeed in the labour market to qualify for permanent residence or they don’t. In this way, the government doesn’t have to fund the services.”

“We all acknowledge giving access to students to those (settlement and support) services from the beginning of their journeys would be a tremendous return on investment for Canada,” says Larissa Bezo, president and CEO of the Canadian Bureau for International Education, a not-for-profit organization that aims to promote and advance Canadian international education.

“There’s a shared responsibility that we have … And in a federation like ours, that’s complex. I’m under no illusion. But we need to do a better job of connecting these dots.”

Coming out of the pandemic, Bezo says, Canada’s global brand has remained strong as Canadian governments and the sector pivoted in supporting international students through the crisis as other countries such as Australia asked their students to go home.

Clear messaging to international students

Balraj Kahlon, who co-founded One Voice Canada in British Columbia in 2019 to support and advocate for international students, says Canada’s international education strategy has been “ruthlessly” successful.

“The whole objective of international education is just to make money and to grow the economy. It has really little to do with education,” says Kahlon. “If we’re honest about what the international education strategy is, it is just to raise Canada’s GDP.”

He says the country’s international enrolment has increasingly been coming from the working poor in developing countries, lured by Canada’s relatively low tuition fees, the chance to work and make money to pay off family loans for the studies, and sometimes misinformation by unscrupulous education agents about the direct pathway for permanent residence.

He says many international students these days are pursuing the cheaper and shorter programs at colleges with the sole intent of immigration, even if they know they can’t afford the tuition fees and their courses won’t get them beyond a warehouse, factory or retail job.

Yet, he says many can’t resist the allure of the opportunity for permanent residence and a life toiling in low-wage, low-skilled jobs in Canada that still pay more than what they would earn back home.

If the international education strategy really aims to attract the best and the brightest, he says, permanent residency should be limited to the students who are at the top in their fields by lowering their tuition and making schooling affordable to them.

“Until you get rid of the profit motive, problems are going to keep coming, because the incentive is always just more numbers,” says Kahlon.

Sixty per cent of international students do plan to apply for permanent residence in Canada, but only three in 10 international students who entered the country in 2000 or later ended up obtaining permanent residence within 10 years.

While some fail to complete their education or secure employment for immigration, others find opportunities elsewhere and leave.

“Higher-education admission policies and procedures have a very different goal than the admission criteria for economic immigrants,” says Grunner, the UBC researcher. “That difference is not always clear to students before they come to Canada.

“The message they get is that Canada wants international students. That’s the policy message that gets communicated. International students are desired by Canada for their labour. We got that message very clear because it says that international students can now work for the next year with unlimited hours. And international students are desired as potential immigrants.”

Diversifying where and what students choose to study

Paul Davidson, president of Universities Canada, says there is capacity to absorb more international students, though that capacity isn’t evenly distributed across the country.

Governments, education institutions, immigrant settlement agencies, local communities and employers all have a stake in ensuring international students’ experience and well-being, he says.

“It’s really important that international students get credible information and are supported in every step of their training,” says Davidson, whose organization is the voice for 93 Canadian universities. “There are people making false claims about what their experience in Canada will be and we need to call that out.”

Denise Amyot, his counterpart at Colleges and Institutes Canada, says the federal government not only needs to diversify the source of international students here (currently 35 per cent from India; 17 per cent from China; and four per cent from France), but also where and what they choose to study.

Her organization released a report last year, calling for new permanent residency streams and supports for colleges to improve their labour market outcomes.

“I would be in favour of accelerating permanent residency for students that are in the areas of skills that we need,” says Amyot, who also would like to see international students be eligible for government-funded co-op and job programs.

“It’s important that students do their homework (and ask), ‘How I will be integrated into the community,’ where they look at the best possible scenario for what they want to do and what’s their intentions moving forward.”

Global Affairs Canada says the government has aimed to diversify the countries of origin of its international students, promote study opportunities, especially outside of major urban centres, and showcase sectors to highlight areas of labour shortages and encourage study in those fields through digital marketing initiatives.

Several targeted international ad campaigns will be carried out to promote programs in STEM, artificial intelligence and quantum technologies, the department says. Consultations are underway to renew the country’s international education strategy.

Striking a balance

Sana Banu, an international student from India, can’t say enough about the amazing experience she’s had at Kitchener, Ont.-based Conestoga College, despite all the challenges her peers face and a pathway to permanent residence that’s full of pitfalls.

It has given her experience that has pushed her out of her comfort zone, says the 29-year-old, who came here in 2018 to study marketing and communication with an undergrad degree and eight years of work experience in advertising back home.

International students are a diverse group, each with their expectations and intentions, and it’s impossible to generalize everyone’s experience.

To Banu, the issues come down to equity — whether it’s about the hefty and uncapped international tuition fees or job opportunities that usually favour permanent residents and citizens.

“The relationship shouldn’t be predatory,” says Banu, president and CEO of Conestoga’s student association, who was recently invited to apply for permanent residence. “It’s a mutually beneficial relationship that international students provide to Canada and Canada provides to international students.

“It’s important that everybody sees the human side of an international student rather than just as a resource to fill your economic gaps and contribute to your economy exclusively. They are humans, who are coming here with expectations, dreams and hopes. And you could do a lot more in treating them with more dignity, equity and compassion.”

Source: How Canada can fix its ‘predatory’ relationship with international students