CDC: COVID-19 Was 3rd Leading Cause Of Death In 2020, People Of Color Hit Hardest

2021/04/02 Leave a comment

More confirmation of COVID-19 racial disparities:

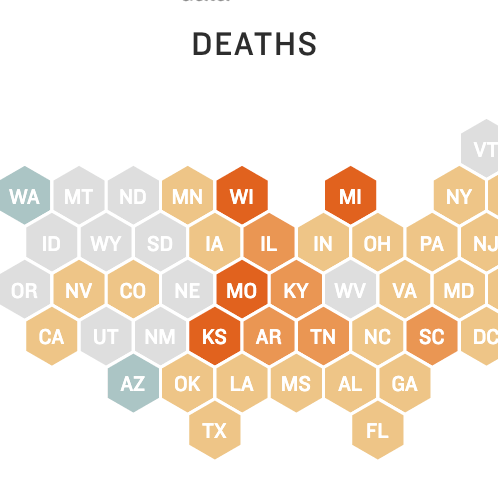

COVID-19 was the third-underlying cause of death in 2020 after heart disease and cancer, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed on Wednesday.

A pair of reports published in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality WeeklyReport sheds new light on the approximately 375,000 U.S. deaths attributed to COVID-19 last year, and highlights the pandemic’s disproportionate impact on communities of color — a point CDC Director Rochelle Walensky emphasized at a White House COVID-19 Response Team briefing on Wednesday.

She said deaths related to COVID-19 were higher among American Indian and Alaskan Native persons, Hispanics, Blacks and Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander persons than whites. She added that “among nearly all of these ethnic and racial minority groups, the COVID-19 related deaths were more than double the death rate of non-Hispanic white persons.”

“The data should serve again as a catalyst for each of us [to] continue to do our part to drive down cases and reduce the spread of COVID-19, and get people vaccinated as soon as possible,” she said.

The reports examine data from U.S. death certificates and the National Vital Statistics System to draw conclusions about the accuracy of the country’s mortality surveillance and shifts in mortality trends.

One found that the age-adjusted death rate rose by 15.9% in 2020, its first increase in three years.

Overall death rates were highest among Black and American Indian/Alaska Native people, and higher for elderly people than younger people, according to the report. Age-adjusted death rates were higher among males than females.

COVID-19 was reported as either the underlying cause of death or a contributing cause of death for some 11.3% of U.S. fatalities, and replaced suicide as one of the top 10 leading causes of death.

Similarly, COVID-19 death rates were highest among individuals ages 85 and older, with the age-adjusted death rate higher among males than females. The COVID-19 death rate was highest among Hispanic and American Indian/ Alaska Native people.

Researchers emphasized that these death estimates are provisional, as the final annual mortality data for a given year are typically released 11 months after the year ends. Still, they said early estimates can give researchers and policymakers an early indication of changing trends and other “actionable information.”

“These data can guide public health policies and interventions aimed at reducing numbers of deaths that are directly or indirectly associated with the COVID-19 pandemic and among persons most affected, including those who are older, male, or from disproportionately affected racial/ethnic minority groups,” they added.

The other study examined 378,048 death certificates from 2020 that listed COVID-19 as a cause of death. Researchers said their findings “support the accuracy of COVID-19 mortality surveillance” using official death certificates, noting the importance of high-quality documentation and countering concerns about deaths being improperly attributed to the pandemic.

Among the death certificates reviewed, just 5.5% listed COVID-19 and no other conditions. Among those that included at least one other condition, 97% had either a co-occurring diagnosis of a “plausible chain-of-event” condition such as pneumonia or respiratory failure, a “significant contributing” condition such as hypertension or diabetes, or both.

“Continued messaging and training for professionals who complete death certificates remains important as the pandemic progresses,” researchers said. “Accurate mortality surveillance is critical for understanding the impact of variants of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, and of COVID-19 vaccination and for guiding public health action.”

Officials at the Wednesday briefing continued to call on Americans to practice mitigation measures and do their part to keep themselves and others safe, noting that COVID-19 cases continue to rise even as the country’s vaccine rollout accelerates.

The 7-day average of new cases is just under 62,000 cases per day, Walensky said, marking a nearly 12% increase from the previous 7-day period. Hospitalizations are also up at about 4,900 admissions per day, she added, with the 7-day average of deaths remaining slightly above 900 per day.

Dr. Celine Gounder, an infectious disease specialist at New York University who served as a COVID-19 adviser on the Biden transition team, told NPR’s Morning Edition on Wednesday that she remains concerned about the rate of new infections, even as the country has made considerable progress with its vaccination rollout.

She compared vaccines to a raincoat and an umbrella, noting they provide protection during a rainstorm but not in a hurricane

“And we’re really still in a COVID hurricane,” Gounder said. “Transmission rates are extremely high. And so even if you’ve been vaccinated, you really do need to continue to be careful, avoid crowds and wear masks in public.”

Source: CDC: COVID-19 Was 3rd Leading Cause Of Death In 2020, People Of Color Hit Hardest