Are there still NDP voters in a province that just passed a religious symbols law? Singh looks to find out

2019/07/20 Leave a comment

Hard to see him squaring the circle on this one.

Will see during the campaign how much time he spends in Quebec compared to other provinces as possible barometer of prospects:

Quebec’s new law on religious symbols makes minorities feel like they don’t belong in the province, says Jagmeet Singh, and he wants to be the one to lead opposition to the legislation in Ottawa.

The leader of the federal New Democrats says this as he is standing in the food court of a mall in Drummondville, Que., surrounded by locals who support the law and think it’s about time immigrants adapted to Quebec’s culture.

If Singh is to hold on to his party’s 15 seats in Quebec, it will mean connecting with voters in places like Drummondville. That won’t be easy.

“Why do you wear that?” one elderly woman asks, pointing to Singh’s yellow turban. She asks him if he’s been in Canada for a long time.

Another man, Réal Lamott, admits it bothered him to see a politician wearing such a visible religious symbol.

“No, I definitely won’t vote for him,” says Lamott, who backed the Liberals in 2015.

Of the NDP’s 15 seats in Quebec, only three are in Montreal. The bulk of them are in the province’s manufacturing heartland, which stretches between Montreal and Quebec City. Drummondville is right in the middle.

The NDP swept the heartland during the Orange Wave of 2011, when the party won 58 of Quebec’s 75 ridings, but since then political affiliations have drifted toward the right, at least at the provincial level.

This region, its economy driven by mid-sized businesses, was critical to the Coalition Avenir Québec’s sweeping victory in October.

The CAQ’s so-called secularism law, which bars public schoolteachers and other authority figures from wearing religious symbols while at work, hasn’t dented its popularity here. Quite the opposite: According to some polls, the party’s popularity has grown since October’s provincial election.

Striding into these headwinds, Singh campaigned this week, visiting ridings in and around Sherbrooke, Trois-Rivières and Drummondville.

He’s tried to tailor the party’s message to local concerns on this tour.

The NDP’s immigration policy, Singh said, will help businesses deal with the labour shortage, which is particularly acute in Drummondville. Its mass transit plan will bring upgrades to the local train service.

And its proposals for the environment will help smaller municipalities prepare for the more variable weather brought on by climate change.

“That’s what people are talking about,” said Drummondville MP François Choquette, who hung onto his seat for the NDP after he was first elected in 2011.

The religious symbols law is a provincial issue, said Choquette: “I’m concentrating on federal issues.”

Critics of the law, known as Bill 21, have been hoping for more vocal opposition from the federal parties.

The NDP, like the Liberals and the Conservatives, has avoided making any commitments to directly back legal challenges of the law.

Singh, though, went one step further this week, pitching himself as the spokesperson for those Quebecers angered by Bill 21.

“There are a lot of people in Quebec who don’t feel this is the right way to go, and I can be their champion,” he said.

The law, he says, is telling young people from religious minorities that the province where they grew up “is now rejecting you.”

Talk of turban ‘an opportunity’

Political observers are skeptical of Singh’s ability to reconcile that aspiration to lead the anti-Bill 21 vote while holding onto seats in the heartland.

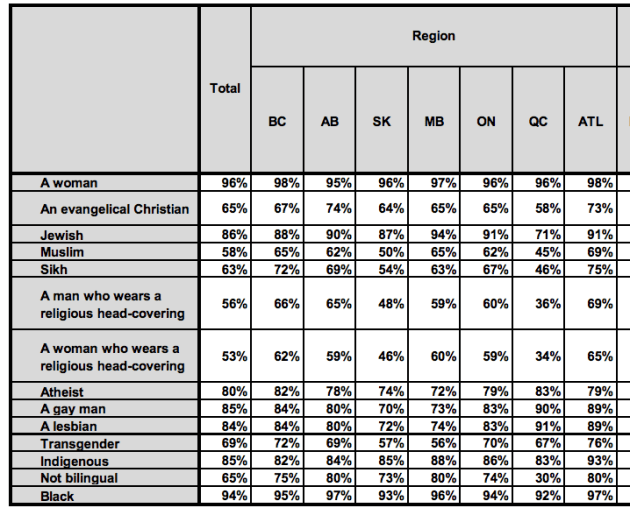

The conventional wisdom among pollsters is that the federal leaders have little to gain in Quebec by being vocal about the issue.

But it would be nigh impossible for Singh to avoid addressing the law head on. Aside from his boldly coloured turban, his kirpan — the small dagger that religious Sikhs carry at all times — was visible as he shook hands in the Drummondville mall.

“Instead of a challenge, I find it’s an opportunity,” he said. “I find it’s the opening of a conversation.”

He offers the woman who was wondering about his turban a quick overview of Sikh history, focusing on the turban’s egalitarian symbolism.

“Well, I think you look quite nice,” she said.

Singh responded by giving her a high-five.