Interesting Harvard Business School alumni survey regarding perceived undermining of US competitiveness by Trump administration policies:

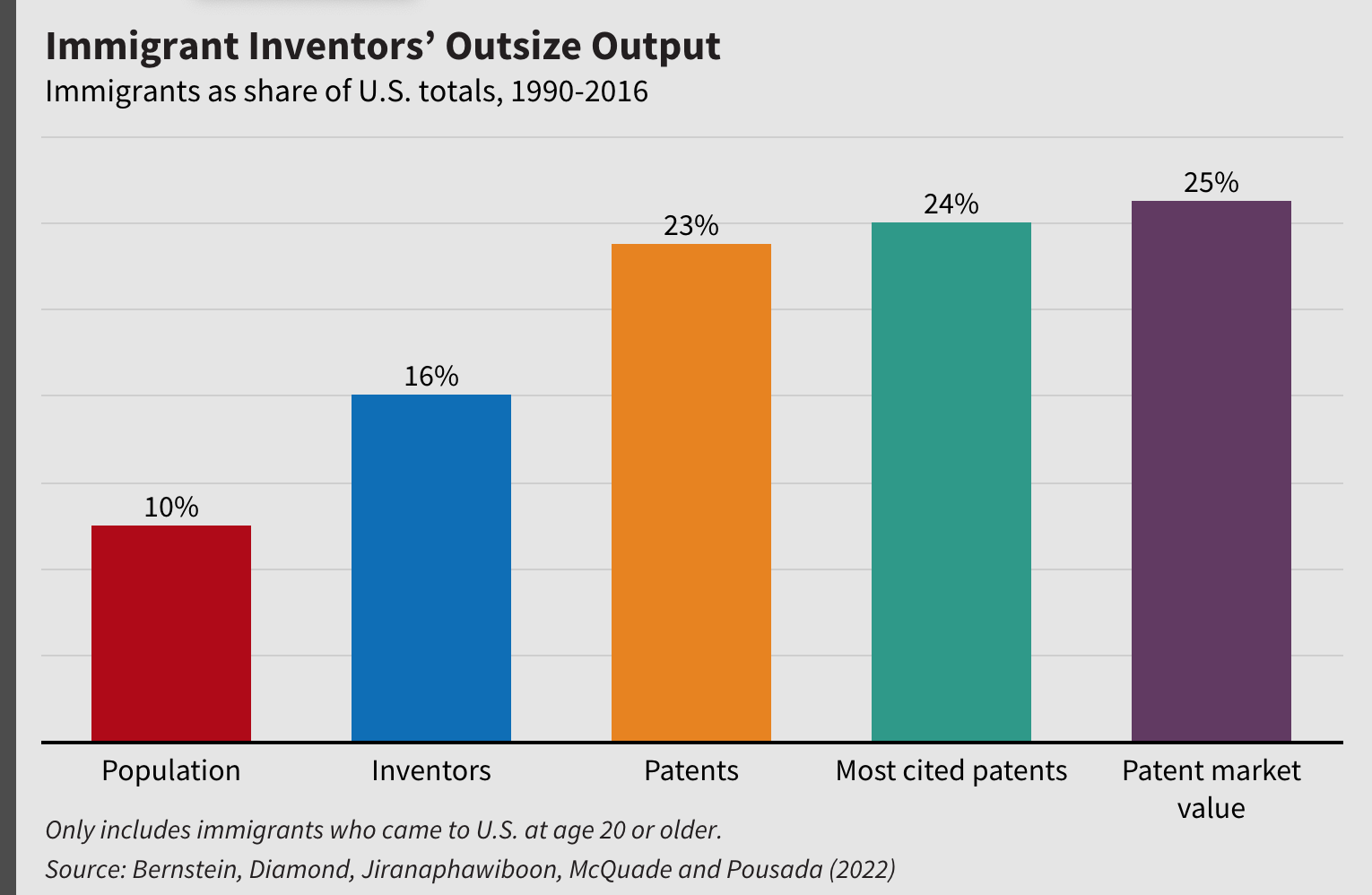

It is no secret that immigration has reshaped American innovation. Immigrants are the backbone of America’s most innovative industries, provide a quarter of our patent applications, and are numerous among our science and engineering superstars.

Taken from World Intellectual Property Organization data (Miguelez and Fink, 2013), Figure 1 shows that America received more than half of migrating inventors from 2000-2010.

Figure 1: Migration of inventors, 2000-2010

Immigrants can be found in times of success and times of crisis. Examples include:

- Among the American companies leading the race toward a vaccine to end the COVID-19 pandemic is Moderna, a Cambridge company with an immigrant co-founder and an immigrant CEO.

- Another firm already conducting vaccine trials is Inovio Pharmaceuticals of Plymouth Meeting, Pennsylvania, led by cofounder J. Joseph Kim. Kim, who came to the United States from South Korea at age 11 without speaking English, was among the pharmaceutical leaders who briefed President Trump on vaccine development in March.

The flow of global talent responsible for bringing these innovators to American shores has been a substantial driver of business creation. As I discuss in my book The Gift of Global Talent, skilled immigration is the world’s most precious resource.

Talent flows to where it’s needed

But talent is movable, and the United States must cherish and protect its prized position at the center of the global talent flow. At a time of crisis when fear is used to shift blame onto outsiders, America is at risk of signaling to global innovators and entrepreneurs, and the promising students who will one day become them, that they cannot have a future here.

Talent flows to where it is most productively utilized and welcome, and while the destination of choice has long been the United States, other countries are increasingly challenging America’s dominance.

“TALENT IS MOVABLE, AND THE UNITED STATES MUST CHERISH AND PROTECT ITS PRIZED POSITION AT THE CENTER OF THE GLOBAL TALENT FLOW.”

By some metrics, their efforts are succeeding. Between 1990 and 2010, America’s share of college-educated migrants within the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development nations fell from about 50 percent to 40 percent.

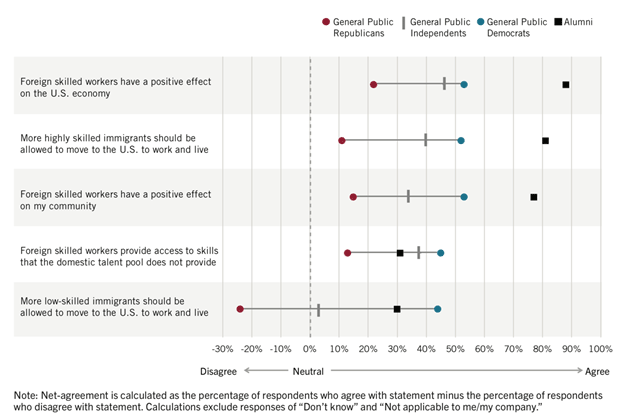

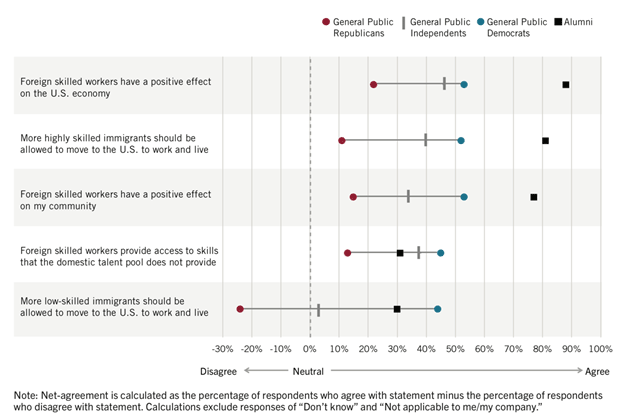

Our recent research captures business leaders’ rising anxiety about America’s complacency in competing for this talent and the negative impact on America’s competitiveness that could result. We surveyed(pdf) thousands of Harvard Business School alumni for their views on immigration.

Our alumni were overwhelmingly supportive of skilled immigration. Over 90 percent said that foreign skilled workers have a positive effect on the US economy, and 87 percent believe that the United States should allow more highly skilled immigrants to move here to work and live (see Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2: Net agreement for belief statements about immigration

Figure 3: Alumni views of immigration system and politics

Alumni also confirmed the importance of foreign skilled workers to their companies’ ability to compete. Nearly one in four said that at least 15 percent of their companies’ US-based skilled workforce was foreign born. Alumni expressed that immigrants were critical for developing better products and services, increasing the quality of innovation, and reaching international customers.

Our alumni warned us, however, that this important competitive advantage is at risk. A majority believe the current political rhetoric around immigration is harming their organization’s ability to attract foreign skilled workers. Nearly 60 percent blamed the US immigration system for causing project delays. And over two-thirds reported that their companies’ operations would be harmed if denied access to foreign skilled workers.

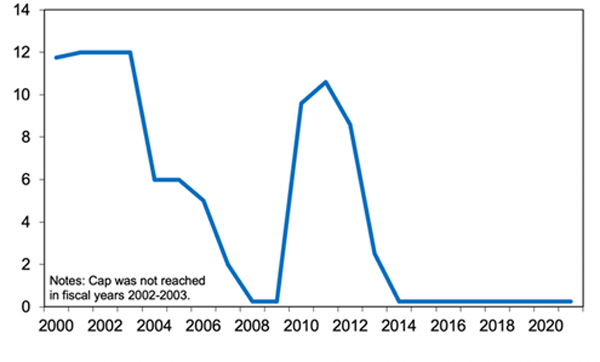

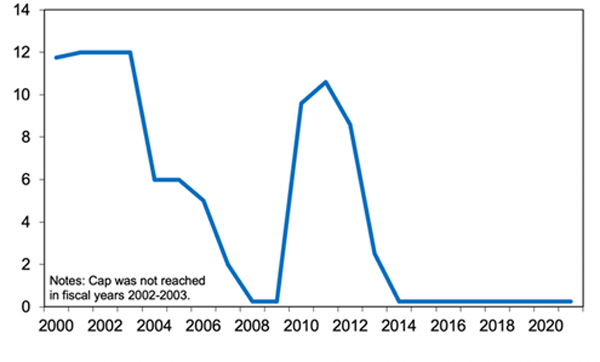

Because immigration is often a political third rail, there are many reasons to be skeptical that the United States will soon find a broad solution. In fact, when it comes to skilled immigration, our research shows more support for minor changes to the current system than for more fundamental reforms. Over two-thirds of alumni supported increasing the number of new H-1B visas issued each year by at least 50 percent. For much of the past decade, H-1B visas have run out within a single week (see Figure 4). Despite even the COVID-19 pandemic, the government received 275,000 applications in March of this year for the 85,000 slots in fiscal year 2021.

Figure 4: Months to reach H-1B visa cap by fiscal year

Structural changes, such as adopting wage ranking for awarding H-1B visas in place of today’s lottery system, did not achieve much support among our alumni. The gap between alumni believing the existing immigration system is harming their businesses and alumni only supporting incremental change is surprising to us. It is unclear whether this reveals a lack of knowledge or actual uneasiness about the policies themselves.

American competitiveness at risk

Either way, the stakes get higher in times of crisis: the recent H-1B visa lottery would have given the same chances to a critical researcher being recruited by Moderna and Inovio (or J&J and GlaxoSmithKline) as it would have to a software code tester working at an outsourcing company.

“WHILE WE MAY TEMPORARILY CLOSE BORDERS AS WE FIGHT COVID-19, BUSINESS MUST ARTICULATE JUST HOW DISASTROUS CLOSING OUR BORDERS LONG-TERM WOULD BE.”

One striking finding was that our alumni were in broad agreement over increasing the allocation of employment-based immigrants within the overall US immigration pool. When asked what share of total immigration to the United States should be employment-based, alumni on average proposed to quadruple today’s 12 percent share. When we surveyed a representative sample of the general public on this same question, we found a similar result—they proposed to triple the share of employment-based immigrants. That result held across all political affiliations, with both Democrats and Republicans proposing to increase the employment-based allotment.

Implementing such a shift could be quite politically controversial depending upon technique, especially if policies shifted visas from family-based channels and diversity programs rather than creating new employment-based visas. But we believe there is a path forward. We can build momentum by getting started with simpler actions like wage ranking H-1B applicants and creating immigrant entrepreneur visas. These quick wins can be stepping-stones towards further reform by proving that we can change our system for the better, despite decades of intransigence.

Most importantly, business leaders should get involved and share the burden with policymakers and academics to educate voters and build support for these policies that ultimately benefit America’s business community.

While we may temporarily close borders as we fight COVID-19, business must articulate just how disastrous closing our borders long-term would be. Some of the recent political rhetoric to halt all immigration, even if later scaled back in practice, endangers the image of America as a welcoming beacon to the next generation of scientists and entrepreneurs. Other countries are creating innovative new programs to attract talent and threaten our competitive advantage, while our government issues executive orders and espouses rhetoric that undermine our promise to the world’s brightest.

Our position at the center of global talent flows is now at risk. Business has both the pressing need, and the capacity, to accept this responsibility. It should.

About the Author

William R. Kerr William Kerr is the D’Arbeloff Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School.

Source: Immigration Policies Threaten American Competitiveness

The immigrant innovation gap

The immigrant innovation gap