Hundreds of appointed positions vacant after 8 years of Trudeau’s government

2023/08/22 Leave a comment

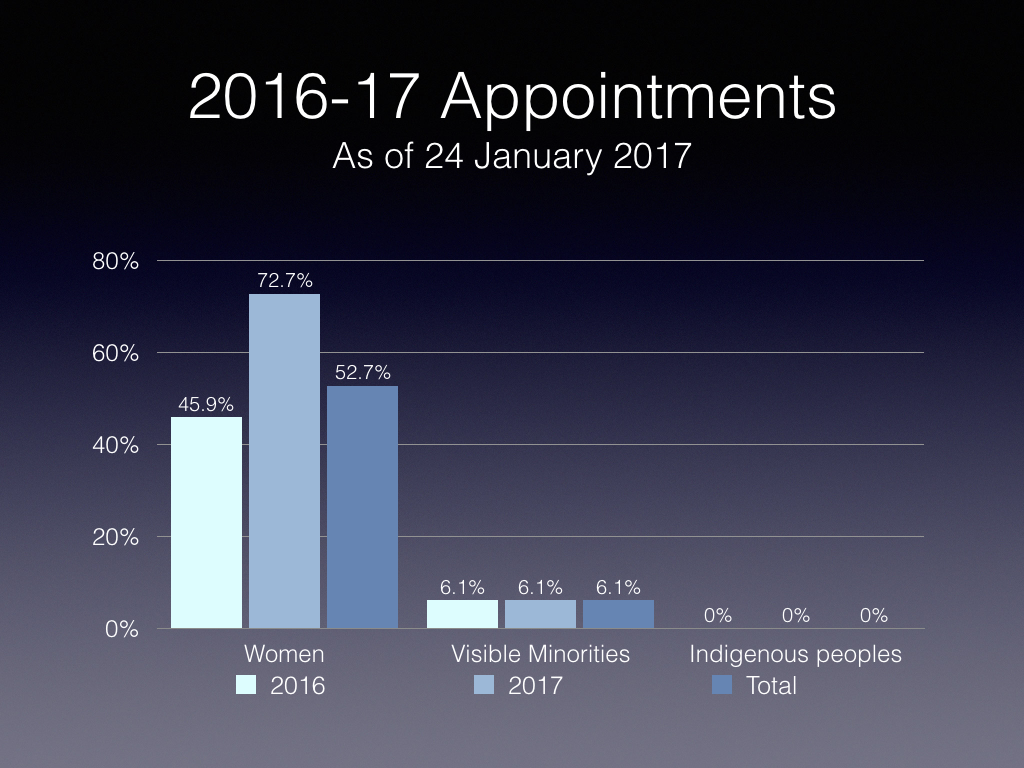

Seems like another example of failure to deliver. But surprising that article makes no mention of the increased diversity of GiC appointments which is one of the successes of the current government (also seen in ambassadorial, senate and judicial appointments).

I am, however, less charitable than UoO professor Gilles Levasseur regarding excusing the government given that they have been in power for 8 years and the system should operate more smoothly:

Almost eight years after Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s government came to power, hundreds of government-appointed positions — from boards of port authorities and advisory councils to tribunals that hear refugee claims or parole cases — are vacant or are being occupied by someone whose appointment is past its end-date.

A CBC news analysis of governor in council (GIC) appointments to 206 government bodies or institutions found that 418 of the 1,731 positions — 24.1 per cent — are either vacant or are being occupied by someone whose appointment has continued past its end date.

Of that number, 280 positions — 16.2 per cent ot the total — were vacant. Another 138 appointees — 7.9 per cent — were past their end-dates and were awaiting either replacement or renewal of their appointments.

Those figures do not include a number of positions currently occupied by someone who is in an acting or interim capacity. Some of those positions have been held by interim or acting appointments for years.

While some GIC appointments come with lucrative six-figure salaries, others provide only per diems of a few hundred dollars plus expenses when board members attend meetings.

Former Conservative prime minister Stephen Harper’s government went on an appointment spree in the weeks before it left office in 2015, leaving very few vacancies and making 49 “future appointments” of individuals whose terms weren’t due to be renewed until well after the election that brought Trudeau to power.

Some experts say leaving hundreds of positions vacant can affect wait times for services or decisions, while leaving boards staffed by people who are past their end-dates can affect an organization’s ability to make decisions.

Other experts, however, argue that the backlog is understandable given the Trudeau government’s decision in its first mandate to overhaul the appointments process to make it less political and boost diversity.

The problem isn’t confined to GIC appointments.

In the Senate, 14 of 105 seats are empty, with vacancies in nine out of 10 provinces. The Senate’s clerk, who manages the day-to-day operations of Canada’s upper house, has been acting in an interim capacity since December 2020.

There are 86 vacancies for federally-appointed judges across Canada, including one seat on the Supreme Court of Canada. All of the seats on seven of the Judicial Advisory Committees set up to assess judicial candidates — including all three committees in Ontario — are vacant.

In June, Supreme Court Chief Justice Richard Wagner warned of an “alarming” shortage of federally appointed justices.

“There are candidates in every province,” Wagner told reporters. “There’s no reason why those cannot be filled.”

Government officials say they are working on filling positions. Stéphane Shank, spokesperson for the Privy Council Office (PCO), defended the government’s appointment process.

“Governor in Council (GIC) appointments are made through an open, merit-based process on a rolling basis throughout the calendar year,” Shank said in an e-mail.

“The process takes into account current and forecasted vacancies, as well as [incumbents remaining in place], to maintain operational integrity of these institutions. Legislative provisions for appointees to continue in office can provide organizational continuity until such time as a new appointment is made.”

No timelines

Shank said the government made 780 GIC appointments in 2022 and will continue filling openings. He said he could not predict when positions such as the commissioner for conflict of interest and ethics — which has been vacant since mid-April — will be filled.

“A new Conflict of Interest and Ethics Commissioner will be appointed by the Governor in Council in due course,” Shank wrote.

Shank pointed to a website with 49 GIC “appointment opportunities” posted. But most of those appointments began the application review process months ago. Ten of the postings list dates in 2022 for application reviews to begin — one dates back as far as March 2022.

The problem isn’t spread evenly throughout the government.

An analysis by ministerial office found the highest percentage of vacant or past-due appointments at Transport Canada: 47.8 per cent of its 230 GIC positions. The boards of several port authorities across Canada consist entirely of vacant positions or board members who are past their appointment dates.

The second highest percentage was at Global Affairs — 42.1 percent of its 19 GIC positions — followed by Housing, Infrastructure and Communities, with 40.9 per cent of its 44 positions.

Nadine Ramadan, press secretary for Transport Minister Pablo Rodriguez, pointed out that the department has more GIC positions to fill than most other ministries.

“Lots of factors go into appointing the best candidates for the roles,” she said. “Due to the complexity of the files across Transport Canada, these roles are often very technical and finding the perfect candidate with the necessary technical requirements for the position takes time.”

But other ministers with large numbers of GIC appointments to make had better track records.

In his former role as minister of heritage, Rodriguez left only 13.3 per cent of 150 appointments vacant or past their appointment dates. He also made several future appointments to renew or replace positions that were near their end dates.

There are two notable exceptions to that track record, however. The board of directors for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) is 58.3 percent vacant or composed of individuals past their appointment dates, while three of eight positions on the National Arts Centre board are vacant.

Former employment minister Carla Qualtrough had more than 100 appointments to manage — including members of the Social Security Tribunal, which hears appeals of decisions involving things like employment insurance and pension benefits. She left that portfolio with a vacancy rate of only 5.5 per cent.

The Prime Minister’s Office plays an overall role in GIC appointments but is also directly responsible for 22 appointments. After two vacancies on the National Security and Intelligence Review Agency were filled Friday, just two PMO appointments remain vacant: the conflict of interest commissioner and the law clerk of the House of Commons

Sen. Percy Downe, who served as director of appointments to former prime minister Jean Chrétien, said it’s important to keep GIC positions filled and a normal vacancy rate should be “three to four per cent at the most.”

These appointments “affect Canadians in many ways,” he said. “They affect their security … they affect the economy.”

Downe said positions that are occupied by people past their appointment dates make it difficult for government departments and agencies to make plans.

“For the boards and agencies, it’s important to know the status as you undertake projects and works that may be required,” he said. “Will this person actually be here in three months or six months? Should we involve them? Should we make them a head of a subcommittee?”

Gilles Levasseur, a professor in law and management at the University of Ottawa, said a higher level of vacancies isn’t surprising given the changes the Trudeau government made to the appointments process and the need to reflect Canada’s diversity.

“People can criticize but we’ve also got to make sure that we understand the system itself and the challenge we’re facing because of these new elements that we didn’t have 10, 15 years ago,” he said. “And because we want to be more open to the society, it takes more time to fill these positions.”

Levasseur said it is not a problem if people are past their appointment dates if they’re doing the job and their presence doesn’t interfere with decision-making. He added the government could do more to let Canadians know about openings.

“A lot of people don’t even know that these positions are available,” he said.

Michael Barrett, Conservative critic for ethics and accountable government, said the level of vacancies is symptomatic of a bigger problem with the current government.

“After eight years of Trudeau, this incompetent Liberal government can’t deliver basic government services like passports and there are backlogs, delays and chaos in everything they touch,” he said in a media statement.

“It has been nearly half a year without an Ethics Commissioner and widespread judicial vacancies are allowing repeat violent criminals to walk free because there are not enough judges to hear cases.”

The New Democratic Party has not yet responded to a request for comment.

Source: Hundreds of appointed positions vacant after 8 years of Trudeau’s government