Diversity in the Bundestag

2022/01/14 Leave a comment

Dramatic change:

When it comes to diversity in the Bundestag, last year’s federal elections in Germany produced the most diverse parliament in the country’s history. The 2021-2025 Bundestag contains a record number (83) of parliamentarians from migrant communities – legislators who are not, or have at least one parent who is not, a German citizen. Moreover, over a third (35%) of legislators are now women, including the legislature’s two first openly transgender lawmakers.

Meanwhile, and for only the third time in its history, the presidency of the Bundestag is also filled by a woman – the Social Democratic Party of Germany’s (SPD) Bärbel Bas, assisted by four female Vice-Presidents from across the political spectrum. Newly inducted Chancellor Olaf Scholz will also preside over Germany’s first gender-balanced cabinet.

This increase in diversity is largely due to a jump in votes for the SPD and the Greens, two of Germany’s most diverse parliamentary parties. Both have gender quotas for candidate selection, with over half of the Greens’ parliamentary party, and over 40% of SPD legislators, being women. The SPD (9.8%) and the Greens (14.9%) also have a greater proportion of candidates from migrant backgrounds than the CDU/CSU (2.9%).

Following the successful coalition talks between the SPD, the Greens and the Liberals, it appears that a more diverse set of legislators will wield power than ever before.

Intuitively, the Bundestag’s greater diversity is to be welcomed. A parliament which better reflects the society it purports to represent fulfils the criteria of descriptive representation: the country’s population is more accurately reflected in the makeup of its legislature.

This symbolic representation can not only engender legitimacy but can also reduce feelings of alienation amongst otherwise marginalised groups.

Given increased rates of misogynist violence, crimes against LGBTQ+ people, and ethnic discrimination in Germany, the greater visibility of minorities in mainstream politics may provide reassurance to those communities that feel vulnerable.

But what about the implications of greater descriptive representation for parliament’s substantive work? Symbolic representation certainly does have its benefits but alone is insufficient.

To be well represented, marginalized and vulnerable groups need parliamentarians to advocate for their interests, transform political agendas, and influence political debate.

There is clear evidence that minority legislators feel a sense of responsibility to do so, be that by asking parliamentary questions, scrutinising legislation, or proposing bills. In Germany, there is certainly legislation which could better reflect the needs and lived experience of minority groups.

Angela Merkel’s National Action Plan, designed to facilitate the integration of refugees and asylum seekers into German society after 2015, focused heavily on language classes and employment as a means of assimilation, and has beencriticised for its failure to combat negative perceptions of, and attitudes towards, immigrant communities.

Similarly, calls for reform to the German law on Self-ID, which currently subjects individuals to large fees and invasive psychological assessment, have to date failed to catch legislators’ attention. The election of two trans representatives may, at a minimum, raise awareness of the issue, and even inform the thinking of governing parties.

Indeed, preliminary evidence seems promising. The Government’s newly minted coalition agreement proposes fundamental change to self-ID laws, and compensation for trans people forced to undergo sterilization in order to legally change their gender identity. Sven Lehmann, a Green MdB, has also been appointed as a government commissioner on gender and sexual diversity, working on LGBTQ+ issues across government departments.

The Government has also committed to introducing a comprehensive strategy (and additional funding) to combat violence against women, and to reforming the asylum process to be more simple, fair, and protective of vulnerable populations.

However, though coalition ministers are supportive, there may still be some limits to the extent to which legislators are able to amend legislation, and actively represent minority groups.

For one thing, although the diversity of the Bundestag increased in 2021, the bar was relatively low to begin with. The share of female legislators is up by just three percent from 2017, and the number of representatives who are female, LGBTQ+, or belong to migrant communities is still low in comparison to the wider population.

For example, only 11.3% of legislators hail from migrant communities, with the largest – Germany’s Turkish community – still vastly underrepresented.

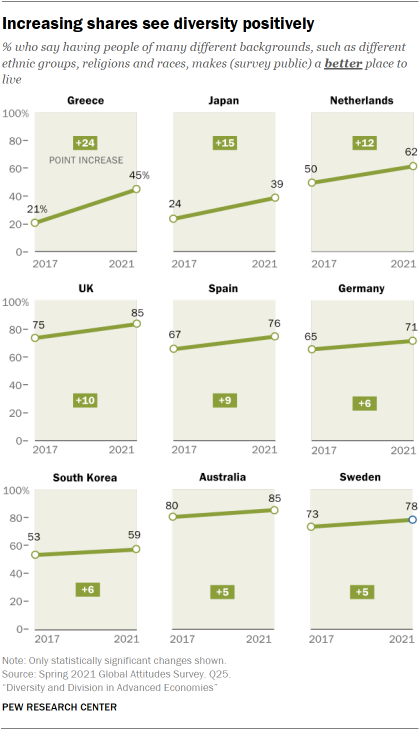

Second, wider societal attitudes are not necessarily conducive to change. As in many other European countries, whilst German attitudes towards LGBTQ+ communities and gender equality are relatively liberal, debate around issues such as gender identity, race, multiculturalism and discrimination is increasingly polarised.

This had led to an increasingly hostile political environment for minority candidates, which is unlikely to encourage political engagement.

Tareq Alaows, a Syrian refugee, campaigned for the Greens in September’s elections on a platform of immigration reform in the hope of becoming the first Syrian immigrant in the Bundestag. However, he was forced to step down after facing a torrent of racial abuse.

A recent study has also found that the 2021 German election campaign was rife with disinformation and conspiracy campaigns which specifically targeted female candidates. Nine in ten female MPs have received correspondence containing misogynistic hate speech and threats.

Third is the question of party politics. Not only are the public increasingly at odds on social issues, but parties are too.

Germany’s three coalition parties may be in step on social issues, but polling ahead of the 2021 election showed a large partisan divide between CDU/CSU candidates and their colleagues from other parties on issues such as migration, or the need to take explicit action to tackle racism and discrimination.

Consequently, although the CDU’s dominance may have faltered in this election, there will still be a substantial bloc of legislators ready to block substantive action on diversity from Government or fellow legislators. In the absence of support from conservatives, parliamentarians’ ability to bring about real legislative change, or shift the attitudes of the wider electorate, may be constrained.

The 2021 session of the Bundestag will be one of its most inclusive. A change in the makeup of parliament, and a more diverse, supportive governing coalition, could mean substantive action on issues such as immigration, self-ID, and misogyny. Such action, however, may be limited.

Illiberal public attitudes, inter-party disputes, and the continued relative lack of lawmakers from minority backgrounds pose formidable hurdles to establishing a distinctive legislative agenda.

There’s a real danger, therefore, that the impact of the Bundestag’s increased diversity may end up being largely symbolic, rather than inspiring tangible change.

Source: Diversity in the Bundestag