Singapore Was A Shining Star In COVID-19 Control — Until It Wasn’t

2020/05/05 Leave a comment

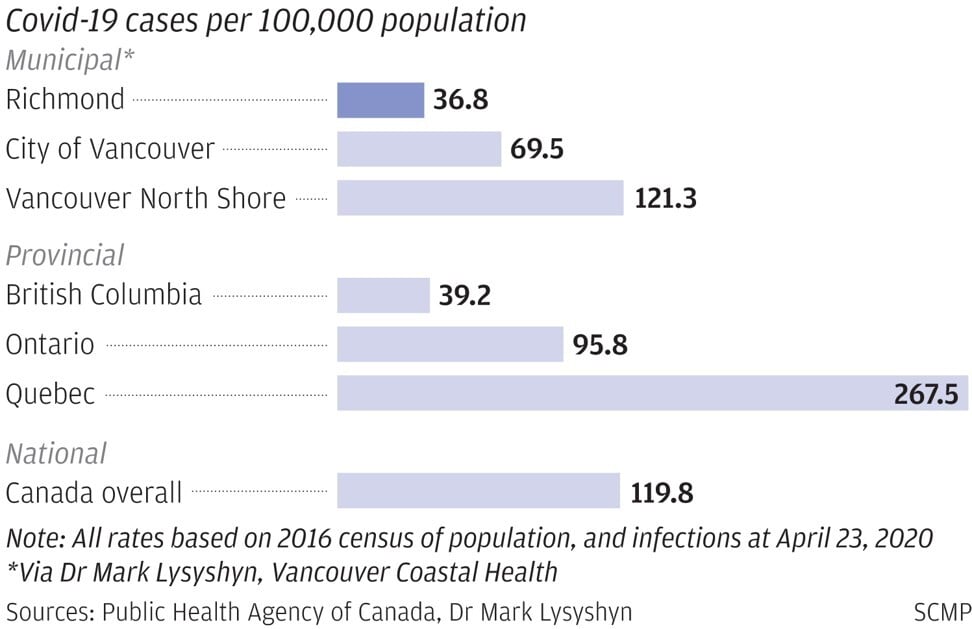

Another example how socioeconomic and immigrant status affects COVID-19 infection rates:

Early on in the coronavirus pandemic, Singapore was praised as a shining example of how to handle the new virus. The World Health Organization pointed out that Singapore’s aggressive contact tracing allowed the city-state to quickly identify and isolate any new cases. It quickly shut down clusters of cases and kept most of its economy — and its schools — open. Through the beginning of April, Singapore had recorded fewer than 600 cases.

By the end of April, however, the case count exceeded 17,000. And not only is all of Singapore now under a strict lockdown, but it has the most coronavirus cases in Southeast Asia.

The vast majority of these cases are in the overcrowded dormitories that house more than 300,000 of Singapore’s roughly 1 million foreign workers — and the number of cases is expected to continue to rise in the coming weeks.

“We have started our testing with the dormitories where there were a high number of cases detected,” Singapore’s health minister, Gan Kim Yong, said in a virtual press briefing this week.

Singapore ordered a lockdown on April 7 in response to an uptick in cases in the general population — and then began to find a significant number of cases in the dorms.

Gan says Singapore is now testing more than 3,000 migrant workers a day but hopes to expand that number. The virus is spreading so rapidly in the dormitories, however, that the Health Ministry hasn’t been able to test all of the suspected cases.

“For dormitories where the assessed risk of infection is extremely high, our efforts are focused on isolating those who are symptomatic even without a confirmed COVID-19 test,” Gan says. “This allows us to quickly provide medical care to these patients.”

Singapore is a small city-state with a population of just under 6 million inhabitants. On a per capita basis, it’s the second-richest country in Asia.

But its economy relies heavily on young men from Bangladesh, India and other countries who work jobs in construction and manufacturing. Singapore has no minimum wage for foreign or domestic employees. The foreign workers’ salaries can be as low as US$250 per month, but a typical salary is $500 to $600 a month.

Speaking to the media, Gan credited extensive screening in the dorms with finding many workers who are infected with SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, but who didn’t appear sick.

“So far, the majority of the cases here have had relatively mild disease or no symptoms. And they do not require extensive medical intervention,” Gan said. “About 30% require closer medical observation due to the underlying health conditions or because of old age.”

As of this week, only a handful of the migrant workers — fewer than two dozen — were in intensive care units.

The city-state is setting up thousands of what it calls “community care beds” in convention centers and other public buildings to isolate and treat coronavirus patients. The hope is that most of the cases can be managed by medical staff in these temporary wards, rather than in hospitals. So far the city has 10,000 community care beds and plans to expand to 20,000 by mid-June.

It’s no surprise that the migrant workers are now being infected, says Mohan Dutta, a professor at Massey University in New Zealand who has done research on these migrant laborers. He says conditions in the dorms put the workers at significant risk of catching a respiratory disease like COVID-19. There are 12 to 20 bunk beds per room.

And even though some of the workers are deemed “essential,” most are no longer allowed to leave the dormitories. “There is little room to move around. They have little room to store their things, which really contributes to this sense of the rooms being unhygienic,” says Dutta.

Dutta, who founded CARE, the Center for Culture-Centered Approach to Research and Evaluation, at the National University of Singapore in 2012, with a focus on marginalized communities, has just published a paper on migrant workers in Singapore during this pandemic.

He says many of them told him they are concerned about whether they’ll get paid during the lockdown (Singapore’s Ministry of Manpower insists they will) and about the overcrowding and lack of sanitation facilities in the dormitories.

Dutta says that in many dormitories, 100 workers share a block of five toilets and five shower stalls.

“There is this sense of panic and fear, and part of that is related to this sense of not being able to move outside of the room,” he says. “Everyone is pretty much stuck in the room at such close proximity.”

Singapore’s Health Ministry has moved aggressively to try to address the coronavirus outbreaks in the housing blocks. The government is trying to find alternative accommodations for people in the hardest-hit dorms, but Dutta says it’s impossible to come up with safe, short-term lodging for more than 300,000 workers.

But he does believe there could be long-term changes that would help the workers. And Dutta hopes this outbreak will force Singapore to examine how it treats this often overlooked population, bringing major changes in how foreign workers are housed and treated.

Meanwhile, the explosion of cases in Singapore over the last three weeks has remained primarily among foreign workers. For example, on May 1 there were 11 new cases reported among Singapore’s permanent residents and 905 new infections among the workers residing in the dorms.

Michael Merson, the head of the SingHealth Duke-NUS Global Health Institute in Singapore, says it’s unlikely the outbreaks in the dormitories will spill over to the rest of the city.

“There’s very little mixing between the foreign workers and the rest of the population,” Merson says. He’s confident that Singapore’s health officials will be able to isolate the infected workers and give them, in his words, “the best medical care possible.”

Nonetheless, the Singaporean government has extended the lockdown for the entire city-state until at least June 1.