Quebec stops publishing daily COVID-19 data despite leading country in number of cases UPDATED: Quebec reversal

2020/06/27 Leave a comment

Update: Quebec announced that it will continue publishing the data on a daily basis following an outcry (Québec recule: les données sur l’évolution de la pandémie seront publiées sur une base quotidienne). Still curious about the rational behind the original decision.

——-

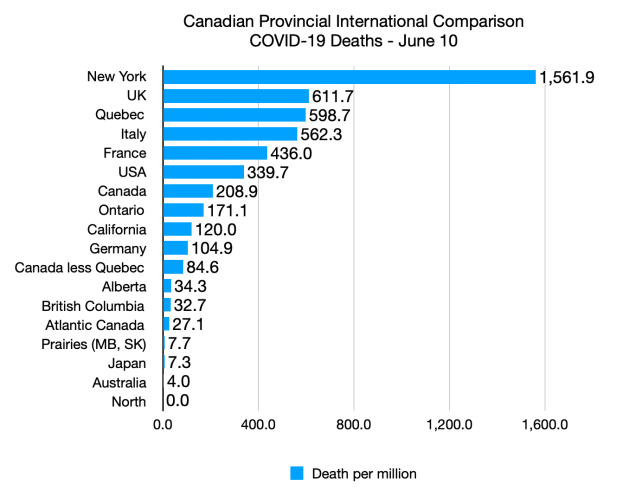

Not sure this strategy will address the “communications” issue as weekly reporting will likely continue to highlight Quebec’s relatively poor performance both domestically and internationally.

Not a great example of transparency and accountability.

Will change my weekly update to accommodate their Thursday release schedule:

Quebec’s Health Ministry says it will only provide weekly reports about COVID-19, rather than providing a daily rundown of the situation.

The province’s public health institute, INSPQ, had also been publishing daily updates, including the number of cases and hospitalizations in Quebec, the number of tests conducted and how many people have died.

The data was also broken down by age and region and showed how many long-term care homes have outbreaks.

The move from daily to weekly updates appears to mean Quebec is providing data less frequently than any other Canadian province, despite leading the country in number of cases. Ontario, which has the second-highest number of cases, continues to provide daily numbers.

As of Thursday, Yukon’s Emergency Measures Organization is providing a public update once per week — but the territory has only 11 confirmed cases.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau addressed the change in his daily news conference on COVID-19 Thursday, saying it’s up to each province to decide how transparent it needs to be.

He also said that Quebec still has a “significant number of cases” and deaths every day.

“I certainly hope that Premier [François] Legault would continue to be transparent and open with Quebecers and indeed with all Canadians as he has been from the very beginning,” Trudeau said.

The Health Ministry and INSPQ will only publish the data on their respective websites every Thursday, the first of them beginning July 2. The ministry will also be sending out a news release with the figures on that day every week.

The decision was first announced in a news release on Fête nationale, the province’s annual holiday.Dr. Horacio Arruda, the province’s public health director, said Thursday that the decision was made in order to provide the public with “more stable numbers,” as fewer confirmed cases each day will make any day-to-day increase appear more significant than it is.

He said this would also allow the province to provide a more accurate portrait of how the virus is spreading, as reporting delays have often prompted a revision of the daily numbers.

“As soon as there is some important data to share with the population, we will do that.” Arruda said, suggesting that the daily updates could return in the event of a second wave of infections.

The government announcement appeared to take the INSPQ by surprise. A notice on its website Tuesday said it would begin limiting its updates to weekdays only, rather than seven days a week.

But on Thursday, following the Health Ministry’s announcement, it said it too would only provide a weekly update. A spokesperson referred any questions to the Health Ministry.

The number of daily cases and deaths in Quebec has declined in recent weeks.As of Thursday, 55,079 people in Quebec have tested positive for the coronavirus that causes COVID-19. That’s an increase of 142 new cases since Wednesday.

There are 487 people in hospital and 5,448 have died. A total of 520,227 tests have come back negative.

The Quebec government has allowed most businesses to reopen, including restaurants, bars, gyms and shopping malls, with physical-distancing restrictions in place.

Source: Quebec stops publishing daily COVID-19 data despite leading country in number of cases