The Mystery Of India’s Plummeting COVID-19 Cases

2021/02/03 Leave a comment

Of interest as had been wondering whether this reflected data issues. Appears not:

Last September, India was confirming nearly 100,000 new coronavirus cases a day. It was on track to overtake the United States to become the country with the highest reported COVID-19 caseload in the world. Hospitals were full. The Indian economy nosedived into an unprecedented recession.

But four months later, India’s coronavirus numbers have plummeted. Late last month, on Jan. 26, the country’s Health Ministry confirmed a record low of about 9,100 new daily cases — in a country of nearly 1.4 billion people. It was India’s lowest daily tally in eight months. On Monday, India confirmed about 11,000 cases.

“It’s not that India is testing less or things are going underreported,” says Jishnu Das, a health economist at Georgetown University. “It’s been rising, rising — and now suddenly, it’s vanished! I mean, hospital ICU utilization has gone down. Every indicator says the numbers are down.”

Scientists say it’s a mystery. They’re probing why India’s coronavirus numbers have declined so dramatically — and so suddenly, in September and October, months before any vaccinations began.

They’re trying to figure out what Indians may be doing right and how to mimic that in other countries that are still suffering.

“It’s the million-dollar question. Obviously, the classic public health measures are working: Testing has increased, people are going to hospitals earlier and deaths have dropped,” says Genevie Fernandes, a public health researcher with the Global Health Governance Programme at the University of Edinburgh. “But it’s really still a mystery. It’s very easy to get complacent, especially because many parts of the world are going through second and third waves. We need to be on our guard.”

Scholars are examining India’s mask mandates and public compliance, as well as its climate, its demographics and patterns of diseases that typically circulate in the country.

Mask and mandates

India is one of several countries — mostly in Asia, Africa and South America — that have mandated masks in public spaces. Prime Minister Narendra Modi appeared on TV wearing a mask very early in the coronavirus pandemic. The messaging was clear.

In many Indian municipalities, including the megacity Mumbai, police hand out tickets — fines of 200 rupees ($2.75) — to violators. Mumbai’s mask mandate even applies outdoors, to joggers on the beach and passengers in open-air rickshaws.

“Every time they fine a person 200 rupees, they also give them a mask to wear,” explains Fernandes, a Mumbai native. “Very stereotypically, we [Indians] are known to break rules! You see traffic rules being broken all the time,” she says, laughing.

But in the pandemic, when it comes to masks, “the police, the monitoring, enforcement — all that was ramped up,” she says.

Authorities reportedly collected the equivalent of $37,000 in mask fines in Mumbai on New Year’s Eve alone.

But the fines and mandates appear to have worked: In a survey published in July, 95% of respondents said they wore a mask the last time they went out. The survey was conducted by phone in June by the National Council of Applied Economic Research, India’s biggest independent economic policy group.

Awareness is widespread. Whenever you make a phone call in India — on landlines and mobiles — instead of a ring tone, you hear government-sponsored messages warning you to wash your hands and wear a mask. One message was recorded by Bollywood legend Amitabh Bachchan, 78, who battled and recovered from COVID-19 last summer.

The mask and hand-washing messages have now been replaced with new ones urging people to get vaccinated; India began vaccinations on Jan. 16.

Heat and humidity

Aside from mask compliance, there’s also India’s climate: Most of the country is hot and humid. That too has deepened the mystery. There’s some evidence that India’s climate may help reduce the spread of respiratory viruses. But there’s also some evidence to the contrary.

A review of hundreds of scientific articles, published in September in the journal PLOS One, found that warm and wet climates seem to reduce the spread of COVID-19. Heat and humidity combine to render coronaviruses less active — though the certainty of that conclusion, the review says, is low. Previous research has also found that droplets of the virus may stay afloat longer in air that’s cold and dry.

“When the air is humid and warm, [the droplets] fall to the ground more quickly, and it makes transmission harder,” Elizabeth McGraw, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Dynamics at Pennsylvania State University, told NPR last year. (However, the science of transmission is still evolving.)

In a survey of COVID-19 cases in India’s Punjab state, Das, the health economist at Georgetown, found that 76% of patients there did not infect a single other person — though it’s unclear why. He and his colleagues examined data collected from contact tracing and found that most patients who did infect others infected only a few other people, while a few patients infected many. Overall, 10% of cases accounted for 80% of infections. One implication, which Das says he’s investigating further, is the possibility of making contact tracing more efficient by first testing a patient’s immediate family members. If no one at all is infected, the process can end there.

“The temperature, of course, is in our favor. We do not have too cold of a climate,” says Dr. Daksha Shah, an epidemiologist and deputy executive health officer for the city of Mumbai. “So many viruses are known to multiply more in colder regions.”

But there’s also some scientific evidence to the contrary, that India might actually be more conducive to the coronavirus: Research published in December in the journal GeoHealth says that urban India’s severe air pollution might exacerbate COVID-19. Not only does pollution weaken the body’s immune system, but when air is thick with pollutants, those particles may help buoy the virus, allowing it to stay airborne longer.

A paper published in July in The Lancet says extreme heat may also force people indoors, into air-conditioned spaces — and thus might contribute to the virus’s spread. The Natural Resources Defense Council has warnedthat extreme heat can lead to a spike in other illnesses — dehydration, diarrhea — that might lead to overcrowding in hospitals and clinics already struggling to treat victims of COVID-19.

Prevalence of other diseases

Another point to consider about India is how many other diseases are already rampant: malaria, dengue fever, typhoid, hepatitis, cholera. Millions of Indians also lack access to clean drinking water, sanitation and hygienic food. Some experts speculate that people with robust immune systems may be more likely to survive in India in the first place.

“All of us have pretty good immunity! Look at the average Indian: He or she has probably had malaria at some point in his life or typhoid or dengue,” says Sayli Udas-Mankikar, an urban policy expert at the Observer Research Foundation in Mumbai. “You end up with basic immunity toward grave diseases.”

Two new scientific papers support that thesis, though they have yet to be peer-reviewed: One study by Indian scientists from Chennai and Pune, published in October, found that low- and lower-middle-income countries with less access to health care facilities, hygiene and sanitation actually have lower numbers of COVID-19 deaths per capita. Another study by scientists at India’s Dr. Rajendra Prasad Government Medical College, published in August, found that COVID-19 deaths per capita are lower in countries where people are exposed to a diverse range of microbes and bacteria.

But experts warn that these two studies are preliminary and should serve only as a springboard for more investigation.

“They’re not based on any biological data. So they’re good for generating a hypothesis, but now we really need to do the studies that will result in explanations,” says Dr. Gagandeep Kang, an infectious diseases researcher at the Christian Medical College in Vellore. “I hope scientists work more on this soon. We need deeper dives into India’s immune responses.”

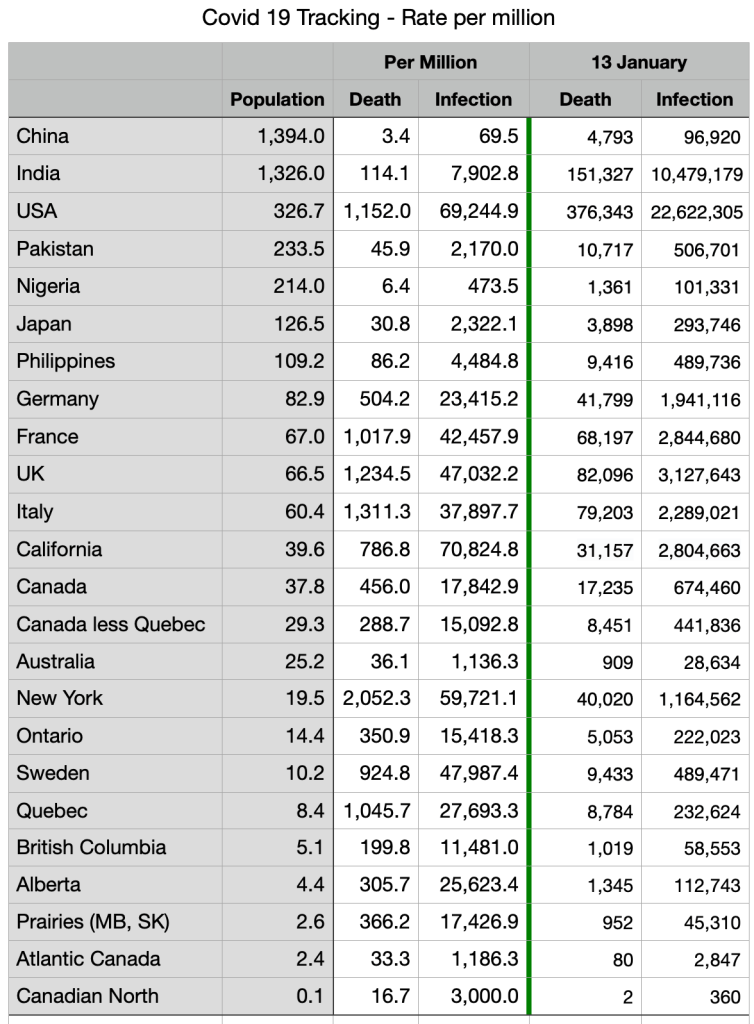

According to Health Ministry figures, the coronavirus has killed 154,392 people in India as of Feb. 1. That’s a mortality rate of 1.44% — much lower than that of the United States or many European countries. (But Brazil’s death rate is higher than India’s, and Brazil and India are both lower-middle-income countries.)

Demographics

India is a very young country as well. Only 6% of Indians are older than 65. More than half the population is under 25. Those who are young are less likely to die of COVID-19 and are more likely to show no symptoms if infected.

A study of nearly 85,000 coronavirus cases in India, published in November in the journal Science, found that the COVID-19 mortality rate actually decreases there after age 65 — possibly because Indians who live past that age are such outliers. There are so few of them.

“Those Indians who do live that long tend to be more healthy than average or more wealthy — or both,” says health economist Das.

Serological surveys — random testing for antibodies — show that a majority of people in certain areas of India may have already been exposed to the coronavirus, without developing symptoms. Last week, preliminary findings from a fifth serological study of 28,000 people in India’s capital showed that 56% of residents already have antibodies, though a final report has not yet been published. The figures were higher in more crowded areas. Last summer, another survey by Mumbai’s health department and a government think tank found that 57% of Mumbai slum-dwellers and 16% of people living in other areas had antibodies suggesting prior exposure to the coronavirus.

But many experts caution that herd immunity — a controversial term, they say — would only begin to be achieved if at least 60% to 80% of the population had antibodies. It’s also unclear whether antibodies convey lasting immunity and, if so, for how long. More serological surveys are needed, they say.

Timing

India’s climate and demographics have not changed during the pandemic. And the drop in India’s COVID-19 caseload has been recent. It hit a peak in September and has declined inexplicably since then.

In fact, India’s numbers went down exactly when experts predicted they would spike: in October, when millions of people gathered for the Hindu festivals of Diwali and Durga Puja. It’s when air pollution is also worst, and experts feared that would exacerbate the pandemic too.

Cases have also declined despite what many thought would be a superspreader event: tens of thousands of Indian farmers camping out on the capital’s outskirts for months.

Shah, the epidemiologist, wonders if, just like more infectious variants of the coronavirus have been discovered in the U.K. and elsewhere, perhaps a milder variant may have started mutating in India.

“Some processes must have happened. This is an evolution of the virus itself. In some places there are mutations happening,” she says. “We need some more deeper evidence and deeper studies.”

The truth is, scientists just don’t know.

“Three options: One is that it’s gone because of the way people behaved, so we need to continue that behavior. Or it’s gone because it’s gone and it’s never going to come back — great!” says Das, from Georgetown. “Or it’s gone, but we don’t know why it’s gone — and it may come back.”

That last option is what keeps scientists and public health experts up at night.

So for now, Indians are kind of holding their breath — just doing what they’re doing — until they get vaccinated.