While an Australian strict travel restrictions much harder to do in Canada given our long land border with the USA and the high level of economic integration, it is striking that Canadian governments have been unable and late in responding to COVID-19, with the results we are familiar with:

This temporary Saskatchewan expat is loving Melbourne this summer, for the reason many of the locals aren’t. It’s cool – not cool as in hip, but low-20s temperature cool. Great for running and biking and walking. Not so great for the beach or dining on restaurant patios and decks.

Those patios and decks are nonetheless open and full (maximum density of one person per two square metres), spilling out onto busy streets full of shoppers. The Australian economy is now projected to grow by 3.2 per cent in 2021, a major turnaround from last July’s estimate of minus 4.1 per cent for this year. Whence this miracle?

Maybe pandemic control has something to do with it. Here, “pandemic control” is not an oxymoron. Australia isn’t an orderly, fastidious society like Japan or hospitable to healthy doses of authoritarian rule like Singapore. It is a raucous democracy with its politics evenly divided between conservative and progressive camps. Last November saw a big anti-lockdown demonstration in Melbourne convened to protest the measures that drove the case count down to zero.

You cannot attribute Australia’s success to logistical genius or Delphic foresight. There were some legendary missteps. The Ruby Princess cruise ship debacle that disgorged a boatload of infected passengers onto the streets of Sydney a year ago. The slapstick hotel quarantine theatre in Melbourne that created the second wave of cases last June. The multi-million-dollar inquiry never did get to the bottom of exactly how, and by whom, quarantine security was contracted out to a company with no experience and ill-trained staff. The State of Victoria cabinet secretary, a cabinet minister, and a secretary (deputy minister) lost their jobs, while others were shunted aside.

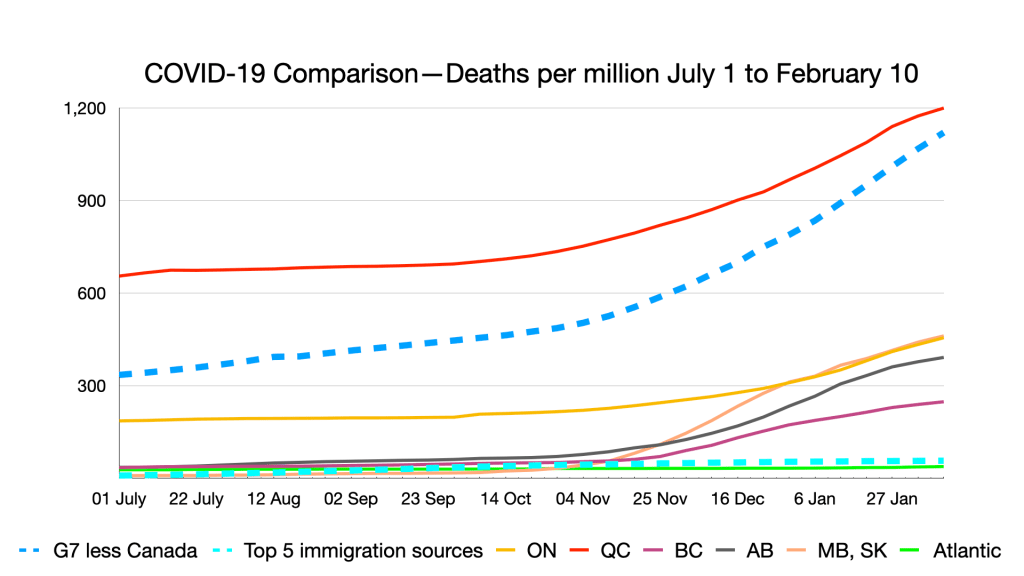

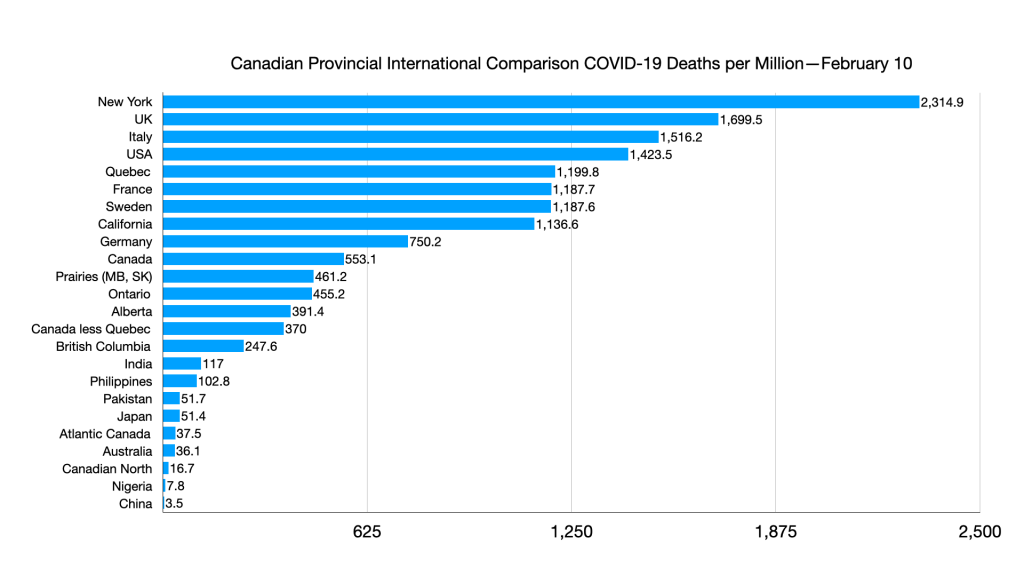

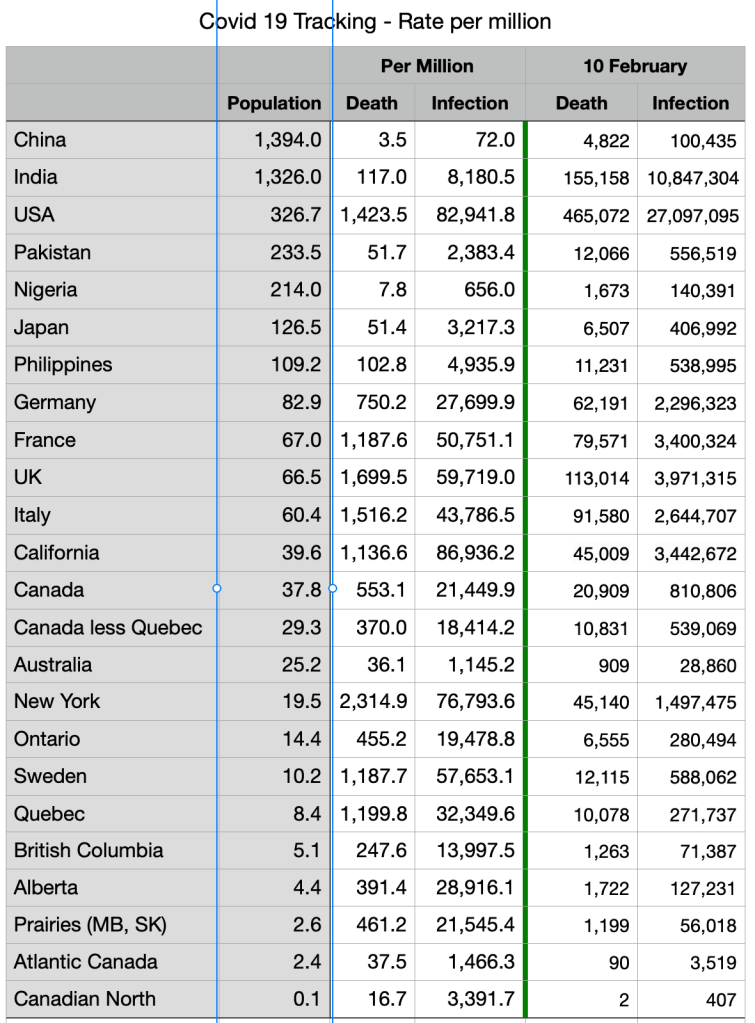

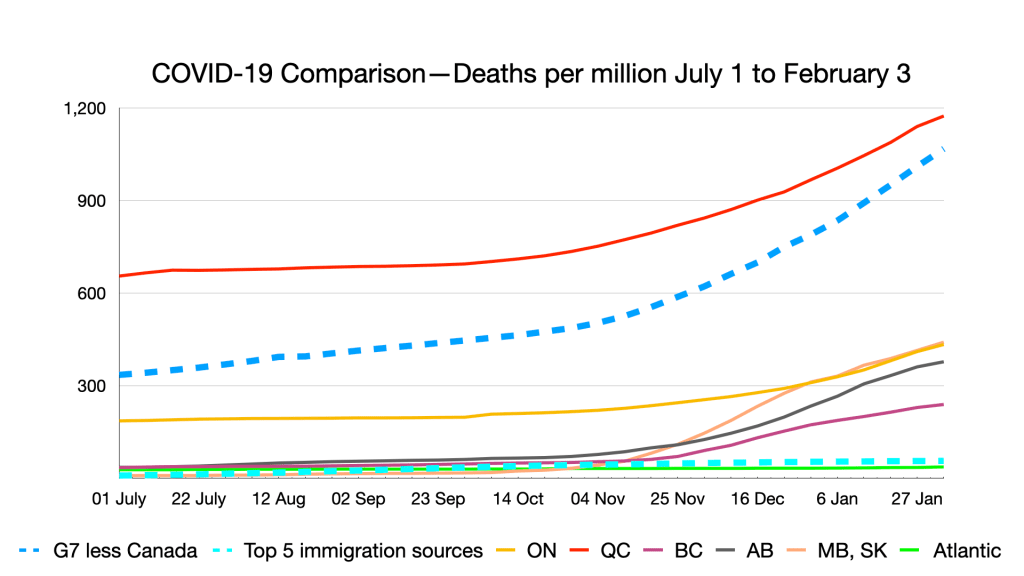

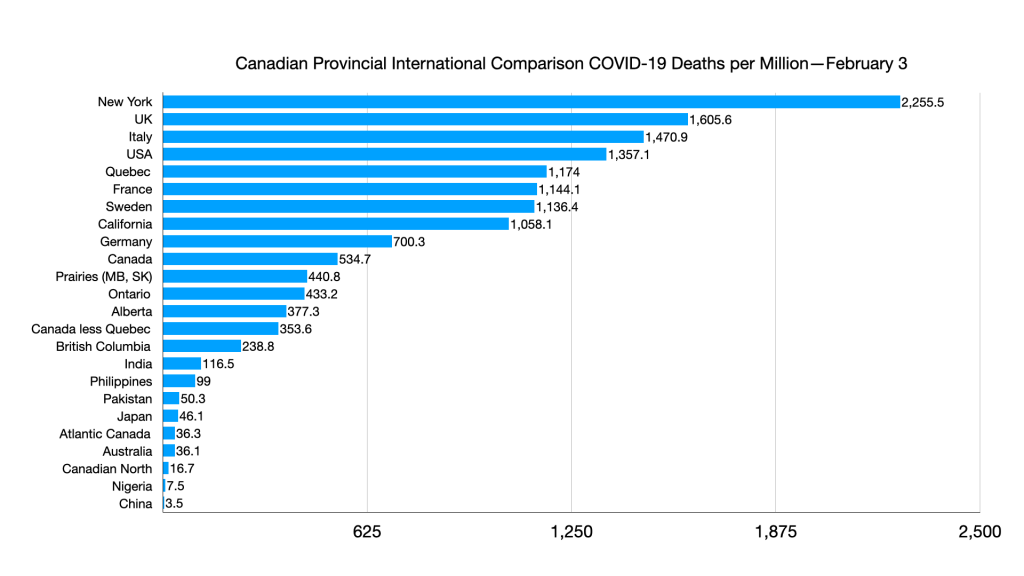

But as of Feb. 5, Australia has had 35 COVID deaths-per-million since the beginning of the pandemic. By comparison, Canada has had 543.

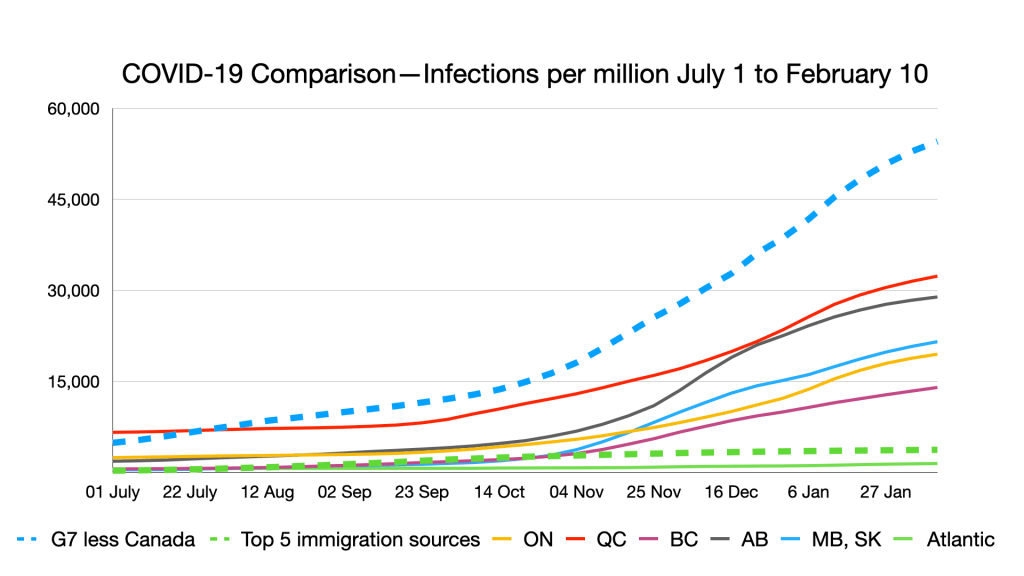

So, what accounts for the difference? Some is luck and circumstance. Australia is an island off the world’s heavily beaten paths. But at the beginning, its numbers were similar to Canada’s. As of March 31, 2020, Australia had 4,763 cumulative cases and Canada had 8,612 (about 20 per cent more per capita). By early February 2021, Canada had 19 times as many cumulative cases per capita.

Early in the pandemic, no one knew with certainty how contagious or lethal it was and which measures were essential to containing it. Different jurisdictions tried different policies and practices. The results of the global experiment are in. What can we learn from Australia?

First, testing is important but is powerless without good policy. Over the past year, there were periods where Australia’s testing rate was about double Canada’s, but since last summer overall rates have converged and at times Canada’s rate has exceeded Australia’s. Testing tells you what you’re dealing with. It doesn’t tell you how to deal with it.

Second, both external and internal travel restrictions are effective. Australian states – over the objections of the national government – are quick to close their borders to each other as well as the outside world. Since last September, the highest daily count of new cases nationally has been 44. Yet even after five months of stable, low numbers, people still had to quarantine for 14 days to go to Western Australia (rescinded as of Feb. 5, 2021).

On Jan. 31, a single case popped up in Perth, in Western Australia: a guard working in the hotel quarantine program. His flatmates tested negative, as have others of his reported contacts. Yet Victoria has closed its border to most populated areas of Western Australia and will fine people up to the equivalent of $4,900 if they enter without a permit.

Third, people are more likely to follow rules if you enforce them. Victoria levied the equivalent of about $29.5 million in fines last year. People were upset. Many resulted from minor infractions and/or confusion about what was permitted. Most weren’t paid and all but the most brazen violators can get the fine rescinded if they go to court and promise to behave. But the government took the heat to make a point. Pandemic control measures carry the force of law. Four hundred people were arrested at the November anti-lockdown rally.

Fourth, decisions are swift and decisive. Australia doesn’t wait for a prolonged spike in numbers. As soon as there is a small outbreak – a single case in Perth, a few cases in the Northern Beaches area of Sydney – the system springs into action. The hot zones are mapped. Activities are suspended. Contact tracing and testing intensify. Perth and the surrounding region are locked down for an initial five-day period – the vaunted circuit-breaker approach that gives the testing-and-tracing system time to nip the contagion in the bud before the numbers get out of hand.

But the most important lesson is that Australia learned and applied the lessons. It gave up on selective restrictions when the modelling and the epidemiology suggested they couldn’t keep numbers stable and low.

The world knew from the beginning that travel was a major risk factor. Australia took that knowledge to heart. Leaders took a whole-of-pandemic perspective, reasoning that in the case of Victoria, which had most of the country’s cases for months, a severe 112-day lockdown would be less damaging to health and the economy than attempts to finesse the risks with more selective policies. The state premiers became pandemic hawks, determined to do whatever it took to avoid greater and more prolonged misery.

I don’t know how closely Australian officials have observed Canada’s pandemic performance. I suspect they would use it as an object lesson in what not to do. There is, of course, no pan-Canadian strategy – that is part of the problem – but too many provinces have catered to special-interest group pleading, played to their political bases, left bars open, made mask-wearing optional, did little enforcement and responded belatedly to emerging threats. They gave the virus a huge headstart before they chased it in earnest.

Policy and practice have to be grounded in an understanding of the citizenry. Fascinating new research reported in The Lancet shows that countries with “loose” cultures of adherence to social norms (like Canada, the U.S., most of Europe) have had infection rates five times higher, and death rates nine times higher, than those with “tight” cultures (such as Singapore, China and South Korea). Australia and New Zealand are in the loose culture camp, but they have succeeded nonetheless. They did not bank on voluntary, universal adherence to sensible guidelines. They did not make suggestions or request adherence. They raised the stakes, communicated unambiguously, came down hard and showed force where force was needed.

For once, the resolve appears to have achieved consensus among governments of different political stripes. New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern is a social democrat, as are three Australian premiers. The other three state premiers are conservatives, as is Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison. Despite their political differences, they’ve all sung largely from the same pandemic-control hymn book.

Now that more virulent mutations are on the scene. Canada needs to steepen its learning curve. The material is not difficult to master. The lessons are clear. The learning from failure has gone on too long. If Canada wants to succeed, emulate success.

Australia’s strategy is worth a close look not because the country is a paragon of hyper-efficiency and extraordinary governance, but because it is not. You don’t have to be perfect to do well. You simply have to say what you mean; mean what you say; pay attention to the science; and accept that while you may be vilified in some quarters for overreach, you invite catastrophe if you underestimate the strength and agility of the virus.