What changes a Conservative government might make to Canada’s immigration policies

2023/11/22 Leave a comment

My latest. Speculative but reasoned (IMO):

With the Conservatives leading the polls, it is worth speculating what changes a Conservative government might bring to immigration, citizenship, multiculturalism, and employment equity policies, and the degree to which Tories would be constrained in their policy and program ambitions. Despite talking about change and “common sense,” they will still be constrained by provincial responsibilities and interests, the needs and lobbying of the business community, and an overall limitation of not wanting to appear to be anti-immigration.

Constraints

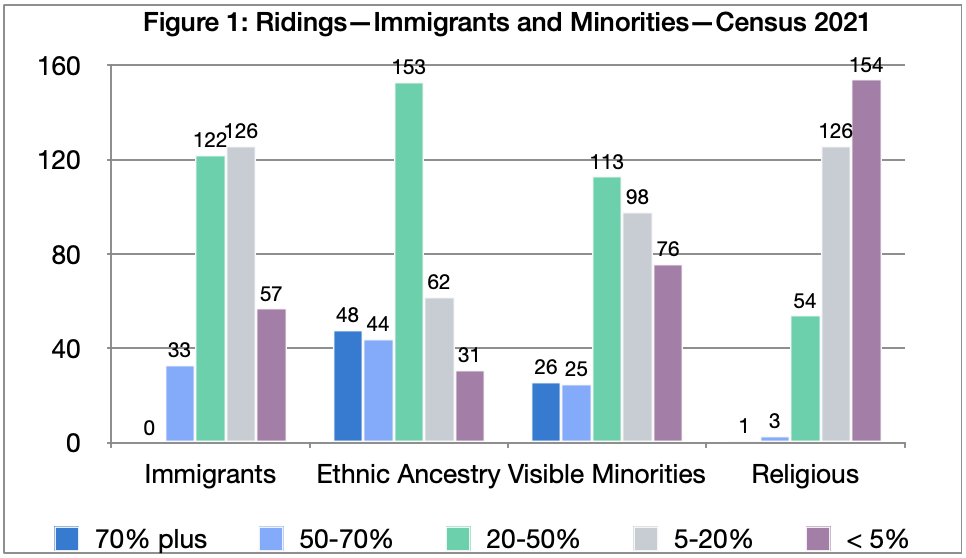

One fundamental political constraint is that elections are won and lost in ridings with large numbers of visible minorities and immigrants, like in the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area, British Columbia’s Lower Mainland, and other urban areas as shown in Figure 1. Arguably, the Conservatives learned this lesson in the 2015 election, where citizenship revocation provisions and the Barbaric Cultural Practices Act signalled to many new Canadians they were not welcome.

Given that immigration is a shared jurisdiction with the provinces, any move to restrict the numbers of permanent residents, temporary workers, and foreign students will likely be met with provincial opposition. All provinces—save Quebec—largely buy into the “more is merrier” demographic arguments. Provincial governments and education institutions rely on large numbers of international students to fund higher education, and thus have already signalled concerns with the current government’s trial balloon about capping students from abroad.

Stakeholder pressures are a further constraint. Business groups, large and small, want a larger population to address labour market needs, and that includes international students for low-value-added service jobs. A larger population also means more consumers. Immigration lawyers and consultants, both in Canada and abroad, benefit from more clients. Settlement and refugee groups can continue to press for increased resources even if evaluations question their effectiveness with respect to economic immigrants. Most academics focus on barriers to immigrants and visible minorities rather than questioning their assumptions. Lobby groups like the Century Initiative and others continue to push the narrative that a larger population is needed to address an aging population, a narrative that is supported by all these stakeholders, and federal and provincial governments (except for Quebec).

Few of these stakeholders seriously address the impact of immigration on housing availability and affordability, health care, and infrastructure, despite all the recent attention to the links between housing and immigration. Most stakeholders are either in denial, claim that ramping up housing can be done quickly as many recent op-eds indicate, or argue that raising these issues is inherently xenophobic if not racist.

Global trends that also could shape a possible Conservative government include increased refugee and economic migrant flows, greater global competition for the same highly skilled talent pool and, over time, expanded use of AI and automation as a growing component of the labour market.

Immigration

Given these constraints and the fear of being labelled xenophobic, Conservatives have focused more on service delivery failures than questioning immigration levels, whether it’s permanent resident targets or the rapid increase in uncapped temporary workers and international students. Poilievre has stated that the Conservative focus will be on the “needs of private-sector employers, the degree to which charities plan to support refugees, and the desire for family reunification,” suggesting greater priority on economic and family immigration categories, as was largely the case for the Harper government. The Conservatives’ recent policy convention was largely silent on immigration. They are engaging in considerable outreach to visible minority and immigrant communities, adopting the approach of former Conservative minister Jason Kenney, “the minister for curry in a hurry.”

That being said, it is likely that a Conservative government would likely freeze or decrease slightly the number of permanent residents rather than continuing with the planned increases (the Liberal government recently indicated that it is not “ruling out changes to its ambitious immigration targets.)”

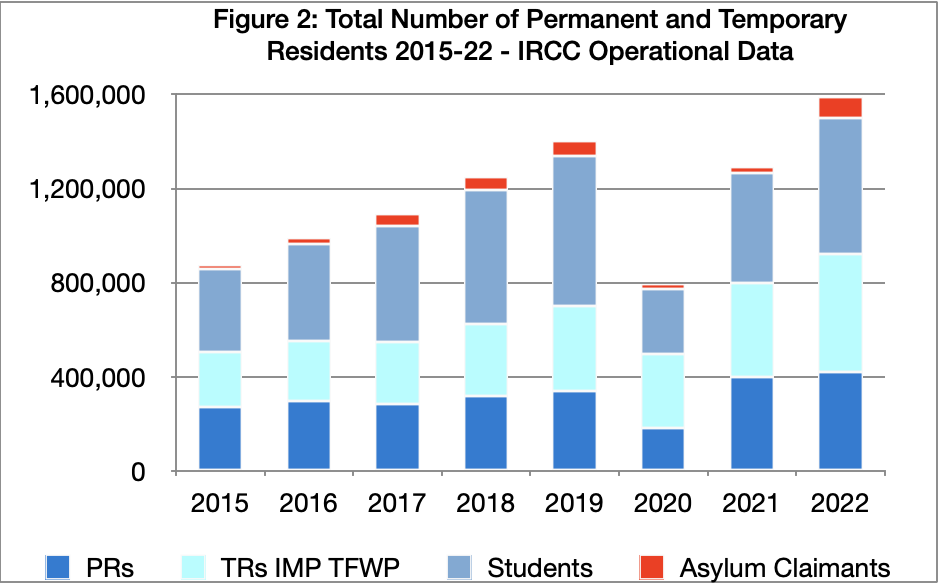

It is less clear whether a Conservative government would have the courage to impose caps on temporary workers given pressure from employers, including small businesses. However, the previous Conservative government did have the political courage to impose restrictions following considerable abuse of the temporary work program, ironically exposed by the Liberals and NDP. Similarly, imposing caps on international students would run into strong resistance from provincial governments given their dependence on students from abroad to support higher education. Even placing caps on public colleges that subcontract to private colleges—which are more for low-skilled employment than education—would be challenging given employer interest in lower-wage employees. They may, however, reverse the Liberal government’s elimination of working-hour caps for foreign students.

The emphasis on charity support for refugees suggests a renewed focus on privately sponsored refugees compared to government-assisted ones. Expect the usual dynamics at play in terms of which groups have preferential treatment (e.g. Ukraine, Hong Kong) that influence all parties, and greater sensitivity to religious persecution, particularly Christians. They are likely to remember how their callous approach to Syrian refugees and the death of Alan Kurdi contributed to their 2015 defeat, and thus be more cautious in their approach to high-profile refugee flows and cases. Whether they would remove health-care coverage for refugee claimants as the Harper government did in 2012 is unclear, but as that was ruled by the Federal Court as incompatible with the Charter, they may demur.

Whether a Conservative government would go beyond the usual federal-provincial-territorial process and provide financial support for foreign credential recognition, or be more ambitious and transfer immigrant selection of public sector regulated professions (e.g., health care) to the provinces is unclear. However, given that regulatory bodies are provincial and, for health care, provinces set the budgets, they may explore this option.

While the simplification and streamlining of over 100 immigration pathways is long overdue, given the complexity for applicants to navigate the system, and for governments to manage and automate it, such longer-term “fixing the plumbing” initiatives are less politically rewarding than addressing various stakeholder pressures.

Given the increased number of asylum claimants, a Conservative government would be likely to restore requirements for claimants to have sufficient funds and an intent to leave, and may consider reimposing a visa requirement on Mexican nationals.

The over $1.3-billion funding for settlement agencies would likely decrease given expected overall fiscal restraint.

Citizenship

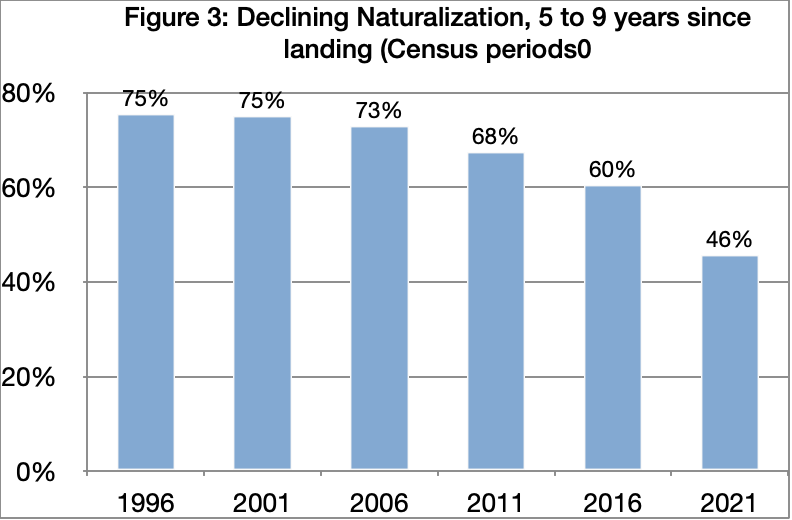

Citizenship is arguably the end point of the immigration journey as it represents full integration into society with all the political rights and responsibilities that entails. This assumption is being challenged by a combination of Canadian economic opportunities being relatively less attractive for source countries such as China and India, along with greater mobility of highly educated and skilled immigrants. As a result, the naturalization rate is declining as shown in figure three.

The previous Conservative government was more active on citizenship than other recent governments. In 2009, it released a new citizenship study guide, Discover Canada, with a greater focus on history, values and the military. It also required a higher passing score on the citizenship test—up to 75 per cent compared to 60 per cent—and different versions were circulated to reduce cheating. Language requirements were administered more strongly, and adult fees were increased from $100 to $530. A first generation cut-off for transmission of citizenship was implemented as part of addressing “lost Canadians” due to earlier Citizenship Act gaps. C-24 amended the Citizenship Act to increase residency requirements from three to four years, increased testing and language assessment to 18-64 years from 18-54 years, and a revocation provision for citizens convicted of treason or terror.

The Liberal government reversed the changes to residency requirements, the age changes for testing and language assessment, and the revocation provision, and promised to issue a revised citizenship study guide and to eliminate citizenship fees. Subsequently, the Liberals amended the citizenship oath to include reference to Indigenous treaty rights in response to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

It is unclear the degree to which the Conservatives will consider citizenship a priority in relation to other immigration-related issues. From an administrative perspective, changing residency requirements again would simply complicate program management, make it harder to reduce processing times, and would not provide any substantive benefit. Re-opening citizenship revocation would simply draw attention to the risks that countries would offload their responsibilities, as the example of former U.K. citizen and Canadian citizen by descent Jack Letts illustrates.

Given that the Liberal government to date has not issued a revised citizenship guide, the Conservatives would likely stick with Discover Canada, issued in 2009. Similar, the existing citizenship test and pass rates, and proof of meeting language requirements would not need to be changed. As the Liberal government never implemented 2019 and 2021 campaign commitments to eliminate citizenship fees, one should not expect any change from the fee increase of 2014.

On the other hand, the pandemic-driven shift to virtual citizenship ceremonies in 99 per cent of all such events would likely to be reversed given strong Conservative opposition in recent discussions at the Standing Committee on Citizenship and Immigration, along with the proposed self-affirmation of the citizenship oath (“citizenship on a click”). It is also likely that a Conservative government may wish to revert to paper citizenship certificates, and away from the option of e-certificates.

The Liberals and the NDP have been trying to weaken the first generation cut-off for transmission of citizenship for those with a “substantial connection” to Canada. Despite the Conservatives opposing this change, largely on process grounds as this was tacked on to a Senate private member’s bill, it is unclear whether they would reverse this change if implemented. However, if some particularly egregious public examples emerge, just as the Lebanese evacuation of 2006 prompted the government to legislate the cut-off given the large numbers of “Canadians of convenience,” they may well decide to act.

The Conservatives may wish to revisit the issue of birth tourism. In 2012, they pushed hard, but ultimately the small numbers known at the time and provincial opposition to operational and cost considerations made them drop their proposal. Since then, however, health-care data indicated pre-pandemic numbers of birth tourists to be around 2,000, although these dropped dramatically during the pandemic given visa and travel restrictions.

The Conservatives are unlikely to revisit the issue of Canadian expatriate voting limitations given the Supreme Court’s ruling that expatriates have the right to vote no matter how long they have lived outside Canada.

Part II

In contrast to immigration and citizenship, a Conservative government would face fewer constraints with respect to multiculturalism and employment equity. Their public criticism of wokeism, their policy resolutions stressing merit over “personal immutable characteristics“, their criticism of diversity, equity and inclusion training, and their criticism of Liberal government judicial, Governor in Council, and Senate appointments all point to a likely shift in substance and tone.

Multiculturalism and Inclusion

The Conservative government moved multiculturalism from Canadian Heritage to Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) given its refocused the program on the integration of new Canadians. Grants and contributions were similarly refocused, and overall funding to the program declined from about $21-million to $13-million (operations and maintenance), and from about 80 to 34 employees. The Conservatives also implemented a historical recognition program to recognize previous discriminatory measures against Ukrainian, Chinese, Italian, Jewish, and Sikh Canadians.

The Liberal government moved multiculturalism back to Canadian Heritage. Funding increased dramatically, with $95-million for Canada’s Anti-Racism Strategy, refocusing the program on anti-racism and systemic barriers to full participation in Canadian society. Additional funding was provided to the Canadian Race Relations Foundation. Greater emphasis was placed on addressing barriers facing Black Canadians such as the Black Canadian Communities Initiative and the Black Entrepreneurship Program. A special representative to combat Islamophobia was appointed. More comparative research by Statistics Canada highlighted differences in visible minority economic outcomes. Heritage months for Canadian Jews and Sikhs were introduced among others.

It is highly likely that resources would be cut sharply under a Conservative government given their overall approach to government expenditures, their general approach to limit government intervention and their scepticism regarding critical race theory, systemic racism, and diversity, equity, and inclusion training. There would likely also be a return to a more general integration focus between and among all groups. They would, of course, be unlikely to curb any of the recognition months or days, given the importance to communities (and their political outreach).

The Conservatives would likely be more cautious about using language like “barbaric cultural practices” in their communications given how that eventually backfired in the 2015 election. One can also expect them to be cautious with respect to Quebec debates on secularism or “laïcité,” such as Bill 21.

Just as the Liberal government cancelled the Conservative appointment of an ambassador for religious freedom, a Conservative government would be likely to cancel the representative to combat Islamophobia.

Hopefully, a Conservative government would neither diminish the value of the mandatory census by reverting to the voluntary and less accurate National Household Survey approach, nor dramatically reduce the budget of Statistics Canada given the impact on the quantity and quality of data and related analysis.

A future Conservative government is likely to revisit the guidelines for funding research away from diversity, equity and inclusion priorities, along with Canada Council, Telefilm, and others, based upon party policy resolutions.

Employment Equity

A Conservative government might reduce the amount and quality of data available regarding visible minority, Indigenous Peoples, persons with disabilities represented in public service, and other government appointments.

The Liberal government expanded public service data to include disaggregated data by sub-group, allowing for more detailed understanding and analysis of differences within each of the employment equity groups since 2017, along with data on LGBTQ+ people. Previous government reports only covered the overall categories of women, visible minorities, Indigenous Peoples and persons with disabilities. It is uncertain whether these reports under a future Conservative government would revert back to only reporting on overall group representation, hirings, promotions and separations. Given that this concerns public service management, it may well decide to continue current practice or the more sceptical elements may press for change.

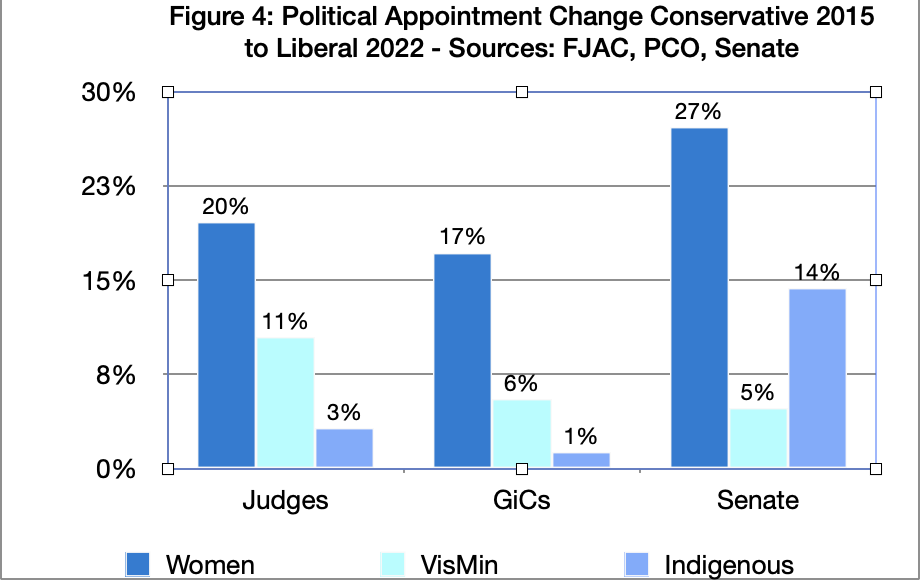

On the other hand, political appointments—judges, Governor-in-Council, Senate—are another matter. Appointment processes are likely to be revised given concerns that the processes introduced by the Liberal government unduly favoured candidates more on the centre-left than centre-right. Figure 4 highlights the increased representation of women, visible minorities and Indigenous Peoples in political appointments.

At the end of the Conservative government, judicial appointment were 35.6 per cent women, two per cent visible minorities and 0.8 percent Indigenous. The Liberal government introduced a new application process that aimed to—and succeeded in—vastly increasing the diversity among judicial appointments. As of October 2022, they sat at: 55.2 per cent women, 12.5 per cent visible minorities, and four per cent Indigenous.

Similarly, at the end of the last Conservative government, Governor-in-Council appointments to commissions, boards, Crown corporations, agencies, and tribunals were 34.2 per cent women, 6.1 per cent visible minorities, and 2.9 per cent Indigenous. Under the Liberal government, the number of women increased to 51.4 per cent, visible minorities to 11.6 per cent, and 4.2 per cent Indigenous by January 2023.

Senate appointments present a more nuanced picture. Conservative appointment of visible minorities was at 15.8 per cent, representing a conscious effort to address under-represented groups, but women, at 31.6 per cent of appointments, and Indigenous Peoples at 1.8 per cent, were significantly under-represented. The Liberal introduction of a formally independent and non-partisan advisory board resulted in a sharp increase in diversity: 58.8 per cent women, 20.6 per cent visible minorities, and 16.2 per cent Indigenous Peoples.

Along with these process changes, the Liberal government expanded annual reporting to include visible minorities, Indigenous Peoples, persons with disabilities, and judicial appointment reporting also included LGBTQ and ethnic/cultural groups. Should a Conservative government decide to stop these annual breakdowns, it will be harder to track any shifts in representation.

The current review of the Employment Equity Act, launched in 2021, has not yet resulted in any public report on consultations and recommendations from the Task Force. Given limited parliamentary time and higher priorities during the current mandate, it is unlikely that any revisions to the Act will be approved. However, should any legislation come to pass, it is likely that a future Conservative government might wish to revisit some of the provisions.

Concluding observations

To date, two overarching themes have driven Conservative discourse: Canada is broken, and the need to “remove the gatekeepers.” The Yeates report confirms that the immigration department is broken, reflecting long neglect of organization weaknesses, a lack of client focus, and, I would argue, an excessive multiplicity of programs that make it harder for clients to navigate, and more difficult for IRCC to manage.

One of the ironies of assessing likely Conservative policies is immigration, citizenship, and related areas all pertain to government being “gatekeepers.” It’s easier to shrink the gate for some policies and programs than others (e.g., government political appointments). Others, such as reducing levels of permanent and temporary residents, are much more challenging given the strength of provincial, business, and other stakeholders opposition. The degree to which a Conservative government is prepared to expend political capital will obviously reflect whether or not it has a majority in Parliament.

The sharp decrease in public support for immigration, given the impact on housing, health care, and infrastructure, likely provides greater flexibility for any future Conservative government. While there is greater flexibility with respect to multiculturalism and employment equity, a Conservative government could also be ambitious with needed immigration reforms for permanent and temporary immigration.

While some have argued that immigration and related issues have become a third rail in Canadian politics, this need not be the case. The concerns being raised are regarding the impact of large and increasing numbers of permanent and temporary migration on housing, health care, and infrastructure, not the racial, religious or ethnic composition of immigrants. These issues affect immigrants and non-immigrants alike and focus on commonalities, not differences.

Source: What changes a Conservative government might make to Canada’s immigration policies