Prompting a needed discussion:

Chandana Hiran loves reading, arts and crafts, and recycling. At 22, she’s enrolled in college, studying to be an accountant. She considers herself a feminist.

But something else is a big part of her identity too.

“I’m slightly dark,” Hiran tells NPR in a phone interview from her family’s Mumbai home, her bold voice suddenly going soft. “I’d be called one of the dark-skinned people in our country.”

In India, colorism is rampant. Darker-skinned Indians, especially women, face discrimination at work, at school — even in love. Some arranged marriage websites let families filter out prospective brides by skin tone.

So it may be no wonder that about half of all skin care products in India, according to the World Health Organization, are lighteners designed to “brighten” or “lift” — essentially to whiten — a user’s skin color. WHO estimates that such products amount to about a $500 million industry in India alone. Until recently, some of them even came with shade cards — like paint swatches — so that users could track the lightening of their skin.

Some products claim to “lighten” the skin using multivitamins such as vitamin B3, and many users have said they’re happy with the results. Other products may contain mercury or bleach, which WHO cautions can damage skin cells. Other skin-lightening treatments, including intravenous and pill formulas, have been linked to liver and kidney damage.

The most popular brand of skin lightener is Fair & Lovely, made by the consumer goods giant Unilever. Generations of Indians have grown up with grocery store shelves lined with Fair & Lovely creams and face washes. They’ve been sold in India since 1975 with a marketing campaign of TV commercials and billboards that equate pale, fair skin with beauty and success.

Those are stereotypes that many find deeply unfair. And as the Black Lives Matter movement spreads across the world, it has prompted a reckoning about skin color in India and a brazen revolt against one of its most popular cosmetics.

Feeling insecure

Being slightly browner than the average Indian, by her own assessment, has left Hiran feeling insecure all her life.

“Even the smallest of things, like not wanting to wear brighter colors or just random people coming to you and saying, ‘Oh, maybe you should apply something on your face,’ ” Hiran recalls. “There is not a single Bollywood actress who could represent my skin tone.”

Instead, Bollywood actresses star in TV commercials for skin-lightening creams.

The Indian beauty queen-turned-actress Priyanka Chopra — who starred in the U.S. TV hit Quantico — is one of the most famous. In 2008, she appeared in a series of promotional videos for a product called White Beauty. She played a forlorn-looking single woman who, in the first episode, watched a slightly lighter-skinned woman strut past with a handsome man on her arm. In later episodes, after she used the skin-lightening cream, the man fell in love with her instead.

Another ad for Fair & Lovely suggests using it before going to a job interview.

Praise for white skin is a theme in popular music too. In a 2015 hit song called “Chittiyaan Kalaiyaan” — which means “pale wrists” in the Hindi language — the male singer croons about how a woman’s pale skin makes him swoon.

“Oh my darling, angel baby, white kalaiyaan drives me crazy!” the refrain goes.

When Hiran was a teenager, listening to such songs, she started using Fair & Lovely. She didn’t even have to buy it; her mother always had some in the family medicine cabinet.

The impact of Black Lives Matter

So that was the backdrop in India this spring, when George Floyd was killed in the U.S. and calls for racial justice echoed around the world.

“Can Indians support Black Lives Matter when we ourselves have so many prejudices?” asks activist Kavitha Emmanuel, founder of a women’s charity in southern India called Women of Worth.

In 2009, Emmanuel started a campaign called Dark Is Beautiful to combat colorism in India. Over the years, while counseling girls, she says she realized how deeply hurt Indian women have been by media messages about skin color.

“In our counseling sessions, this would keep surfacing. [They would keep] saying, ‘I am dark,’ ” she told NPR by phone from her home in Chennai. “It is not just about self-esteem in terms of their looks, but it also affects their overall performance in life.”

A study confirms that the scenes in TV commercials for skin-lightening creams may sadly be accurate. A 2015 report by professors at Southern Illinois University and the Rochester Institute of Technology found that in India:

“A woman’s dark skin can preclude her from entering positions such as news anchor, sales associate, flight attendant and even receptionist because these jobs require exposure to and interaction with the public, who will judge her as unattractive, unworthy and incompetent. Fair-skinned women, conversely, are seen in most of these roles; their skin tone grants them unearned privilege and power within organizations as a result.”

Emmanuel says many Indians now expressing support for Black Lives Matter in the U.S. are blind to such discrimination against racial and religious minorities at home. Many of the same celebrities tweeting about racial justice in the U.S. have actually starred in ads for skin-lightening creams.

Bollywood backlash

Among the first Indian celebrities to express public sympathy after Floyd’s killing in the U.S. was the film star Chopra, who posted a lengthy message on Instagram in May with some of Floyd’s last words: “please, i can’t breathe.”

“There is so much work to be done and it needs to starts at an individual level on a global scale,” she wrote. “We all have a responsibility to educate ourselves and end this hate.”

Her comments drew a backlash online. When Chopra’s husband, American singer/songwriter Nick Jonas, tweeted that he and his wife “Pri” have “heavy hearts” over “systemic racism, bigotry and exclusion,” one user replied: “Was pri’s ‘heart heavy’ before or after she promoted skin lightening creams?”

Chopra has not replied to the tweets. But in a 2017 interview with Vogue India, she said she regretted appearing in ads for skin-lightening products. “I used it [when I was very young]. Then when I was an actor, around my early twenties, I did a commercial for a skin-lightening cream. I was playing that girl with insecurities. And when I saw it, I was like, ‘Oh s**t. What did I do?’ ” Chopra was quoted as saying.

She told Vogue that she now sympathizes with girls who feel insecure about their skin tone and has turned down offers to star in any more such ads.

Human rights activists in India have also accused Chopra and other Indian celebrities of hypocrisy for expressing sympathy for Floyd and outrage over his killing but not condemning similar violence against minorities, particularly Muslims, in India. In recent years, under Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Hindu nationalist government, attacks on India’s minority Muslims have skyrocketed. Dozens have been lynched in the streets with little public outcry.

Colonialism and caste

Emmanuel and others trace India’s color discrimination back to the colonial period when mostly white Britons ruled over darker-skinned Indians. But its roots may go back even further than that — to Hinduism’s ancient caste system, roughly based on a hierarchy of professions people are born into.

Historians of ancient India say discrimination based explicitly on skin color has never been part of the Hindu caste system. But it may have evolved over time. For centuries, members of the less privileged, lower castes traditionally did manual labor outdoors under the sun.

“The British colonizers were able to build on India’s existing caste system. So the upper-caste people who were powerful had fairer skin. And the lower-caste people, when they would work outside, those castes started having darker skin [from prolonged sun exposure],” explains Neha Dixit, an Indian journalist who has studied the history of colorism and written about her own experience as a slightly darker-skinned woman. (The euphemism her relatives used for her skin color is “wheatish” — the color of wheat.)

“We have actually internalized all those prejudices,” she says. “So anybody with fairer skin is supposed to be better off than a dark-skinned person.”

Those stereotypes have been reinforced in India for millennia. But modern ideas of racial equality — and the Black Lives Matter movement — are slowly making a dent. A landmark case against caste discrimination is currently under litigation in California, where Indian American tech workers are accused of discriminating against a colleague because he’s a member of a lower caste.

New name, same cream

A few years ago, when she was in her late teens, Hiran, the accounting student, stopped using Fair & Lovely cream. Unilever says its products do not contain potentially harmful bleach or mercury. But Hiran’s decision had more to do with a maturing sense of self rather than any health concerns, she says.

“I started to realize, OK, maybe the problem is not with me. Maybe I’m not supposed to look any other way,” she says. “And I’m not supposed to feel insecure about my own skin.”

This year, Hiran started an online petition to get the name of the product changed. It’s one of several such petitions that have flooded the Internet in the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement.

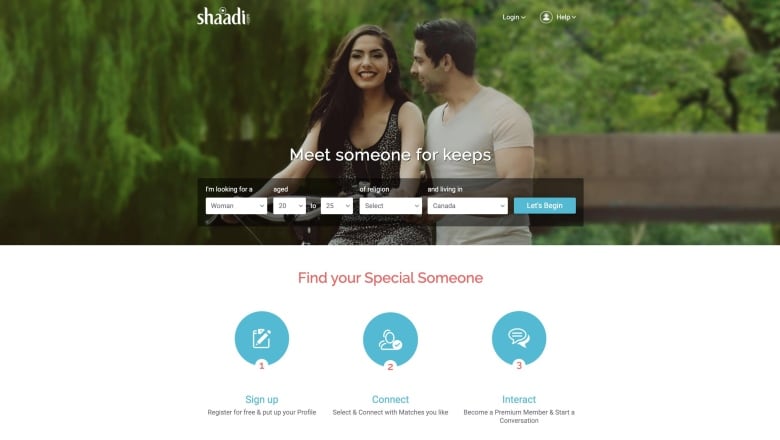

A Texas woman of South Asian descent, Hetal Lakhani, also started an online petition against Shaadi.com, one of the most popular matrimonial websites, demanding that it remove a function that allows users to search for potential partners on the basis of their skin color. Last month, the website obliged, issuing a statement saying that it “does not discriminate” and that the skin color filter was a “product debris left-over in one of our advanced search pages.”

Then, in late June, Fair & Lovely’s manufacturer, Unilever, made an announcement: It’s removing any references to “fair/fairness,” “white/whitening” and “light/lightening” from all of its packaging.

“We are fully committed to having a global portfolio of skin care brands that is inclusive and cares for all skin tones, celebrating greater diversity of beauty,” Sunny Jain, president of the company’s beauty and personal care division, was quoted as saying. “We recognize that the use of the words ‘fair,’ ‘white’ and ‘light’ suggest a singular ideal of beauty that we don’t think is right.”

But even though the packaging now says only that the product moisturizes and gives a pink glow, these terms are understood to be euphemisms for lightening your skin.

This month, Unilever’s Indian branch announced a new name: Glow & Lovely. Its men’s product line will also be rebranded, as Glow & Handsome. The company says the name changes will happen in the coming months.

The cosmetics brand L’Oréal says it’s making a similar change.

But some activists say that’s not enough — that it’s not the names that needed to be scrapped but the products themselves. Another big company, Johnson & Johnson, says it’s discontinuing two of its skin-lightening products altogether.

Souvenir tube

Hiran calls the Fair & Lovely name change “a step in the right direction.”

“It’s not a small thing that Fair & Lovely has done. Because this brand has thrived all these years on the insecurities of women. This is really changing the narrative,” she says. “But it’s only the first step toward being more inclusive and diverse. No matter what you call it, it’s still going to be offensive.”

Even though she hadn’t used the product in years, Hiran says she recently found an old tube of Fair & Lovely in her medicine cabinet. She says she’ll probably hold on to it.

“Now it’s going to become a souvenir,” she laughs.

So the Fair & Lovely label will soon be history. But the question remains as to how long these skin-lightening products — whatever they’re called — will remain in India, along with the attitudes behind them.

Source: Black Lives Matter Gets Indians Talking About Skin Lightening And Colorism