USA: There Are 11,073 Muslims In Federal Prisons But Just 13 Chaplains To Minister To Them

2021/07/14 Leave a comment

The previous conservative government largely cancelled the chaplain program with respect to non-Christian chaplains in 2012 (Non-Christian prison chaplains chopped by Ottawa). Not sure what the current situation is:

Abdul Muhaymin al-Salim converted to Islam during his incarceration on drug charges at a federal prison in South Carolina from 2004 to 2014. In his first year there, the 49-year-old remembers a Muslim volunteer coming to the prison a couple of times a month to lead religious services.

Then, in the second year, during Ramadan, a holy month for Muslims, the volunteer was no longer allowed in the prison. Al-Salim never found out why.

“There were instances where we could have been denied or not received the proper representation or resources that we needed,” he said.

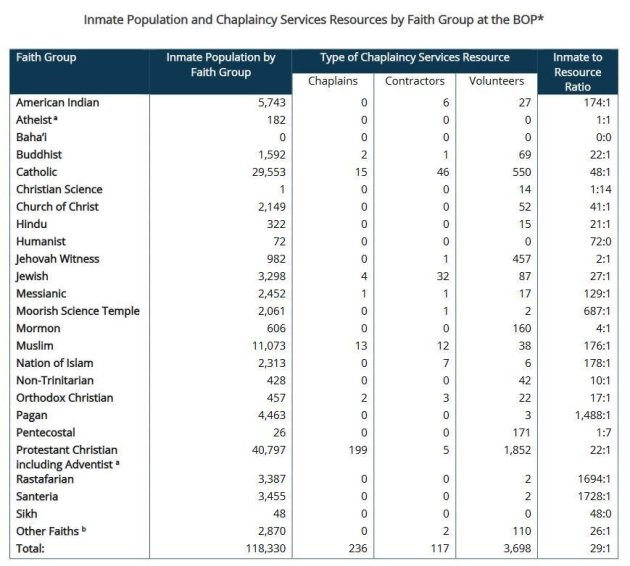

Muslims, the third-largest faith group in federal prisons, are significantly underrepresented among the chaplaincy, according to a Department of Justice inspector general report released last week. Currently, 6% of federal prison chaplains are Muslim, while 9.4% of inmates identified as Muslim.

As of March 2020, 199 of the 236 federal prison chaplains, or 84%, were Protestant Christian, even though that faith group makes up only 34% of inmates. There were no more than 13 Muslim chaplains in the past six years working at federal prisons — and that number remains today, even though the number of Muslim inmates has grown during that time, to 11,073.

The challenges in recruiting Muslim chaplains have persisted within the Federal Bureau of Prisons for years, the report says. In response to a 2004 inspector general report that highlighted a significant shortage in Muslim chaplains, the bureau said it tried to attract a greater number through an on-site program that allowed prison employees to acquire the necessary skills to become a chaplain. But those efforts were unsuccessful, resulting in only one Muslim chaplain trained since 2006. And the number of Muslim inmates has more than doubled since then.

“Oftentimes, this will have a negative effect because you’re left to the whims of whoever is in charge of the chaplain’s department,” said al-Salim, who now works at the Tayba Foundation, where he mentors incarcerated Muslims. “There’s nobody there to help them gain that grounding that they need.”

The needs of the federal prisons’ Muslim population are underserved without chaplains, Muslim leaders say. Because most religious services have to be led by a chaplain, not having Muslim clergy means the services get canceled. When Muslim chaplains are employed, they also make sure Muslim inmates have access to books, prayer rugs and halal meals and that they can freely practice their faith.

Why prospective prison chaplains have been discouraged from applying

“The Bureau of Prisons is committed to ensuring that inmates of all faiths can practice their religion and participate in religious services while also maintaining appropriate safety and security measures,” spokesperson Donald Murphy told NPR in a statement.

Based on recommendations from the inspector general’s office, the bureau is “making changes to improve management and oversight over its chaplaincy program,” Murphy added.

To recruit additional Muslim chaplains, the bureau said it is working with current prison chaplains and seminaries to find candidates.

The bureau is also considering waiving requirements that chaplains must be a certain age, have a graduate-level theological degree and have completed coursework in interfaith study. That would make it easier for religious leaders like Imam Sami Shamma. A chaplain at the Connecticut Department of Corrections for over eight years, Shamma said he hasn’t been eligible for a federal position because he is 65 — over the 37-year age limit for appointment. Neither could Imam Abu Qadir al-Amin, who wanted to be a chaplain at a federal prison in Dublin, Calif., where he volunteered. But he couldn’t qualify because he didn’t have access to higher education.

“Some of the more effective leaders are not necessarily people who went to school for what they’re doing now,” al-Amin said. “They’re more inspired leaders that can make a real contribution to people’s lives who are in that restricted environment and need someone who understands their lifestyle, what led them to be there in the first place, and then can more appropriately develop strategies that address the needs of them returning.”

There’s another reason it’s difficult to recruit Muslim chaplains: Ordination is required by the bureau, but Muslims do not formally ordain religious leaders. And often Muslim communities live far from the prisons, requiring the chaplains and their families to relocate. In addition, Muslim chaplains in correctional facilities often face criticism by people claiming that they are spreading an extremist interpretation of Islam to the prisoners, according to a Harvard University report.

In the meantime, the prisons are filling the gap through contracted religious services providers and trained chapel volunteers. But even with volunteers and contractors, who don’t work full time, there is only one Muslim chaplain per 176 inmates, according to the latest inspector general report.

“If they’re actively recruiting Muslim chaplains and they want to employ Muslim chaplains in the federal system, then they should maybe sit down with Muslim leaders in the community and discuss a strategy for filling that vacuum,” al-Amin said.

Despite the chaplain shortage, the bureau has made incremental progress in accommodating Muslims’ religious practices. In 2019, for instance, it changed its guidelines to allow Muslim inmates to pray in groups.

State prisons face a similar shortage of Muslim chaplains

There’s also a shortage of Muslim chaplains at state prisons, Shamma says. While he used to rely on volunteers to help, they have not been allowed to do so during the pandemic. That has sometimes meant canceled services for the almost 200 inmates he serves.

Some state prisons, with larger Muslim populations, have better resources.

Tariq MaQbool, a 44-year-old Muslim incarcerated at the New Jersey State Prison, told NPR through the Prison Journalism Project that the Muslim chaplain there is a “blessing.” He regularly attends Friday prayers and Islamic talks led by the chaplain.

But MaQbool is still advocating for other ways to practice his faith, including access to halal meals and Islamic literature.

Source: There Are 11,073 Muslims In Federal Prisons But Just 13 Chaplains To Minister To Them