America’s immigrant voters and the 2024 presidential election

2024/11/15 Leave a comment

Useful detailed analysis:

…Immigrants are a diverse, growing, and actively engaged voter base

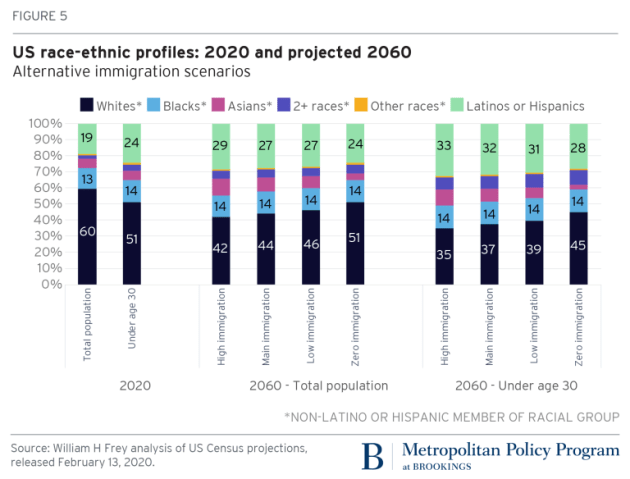

Of the nation’s nearly 46 million total immigrants (about three-fourths of which are U.S. citizens or permanent residents), migrant voters or naturalized citizens, at roughly 24 million, constitute most of the migrant pool and roughly 10% of the total U.S. electorate. Since 1965, when U.S. law expanded voluntary immigration from non-European nations, the migrant cohort has grown significantly. It has increased from about five percent to 13.9% of the U.S. population today and shifted from being predominantly white (80%) and Western to increasingly majority-non-white and less Western. Roughly two-thirds of that growth stems from Latin America and Asia, and to a lesser extent, from other regions including Africa, the Caribbean, North America, and Europe. Stretching across the globe, this rich mosaic of racial and ethnic groups includes Asians, Arabs or Middle Eastern and North Africans (MENA), sub-Saharan Africans, Caribbean groups, Latinos, and white immigrants, and stands in stark contrast to the mostly white, U.S.-born electorate.

At the ballot box, evidence shows that foreign-born voter turnout has typically lagged behind the general electorate, partly due to navigating both the bureaucratic naturalization and voter registration processes. Nonetheless, distinct differences among racial and ethnic subgroups, along with a highly politicized environment, particularly around immigration in recent years, has affected this trend.

Foreign-born Asian and Latino groups vote at higher rates thantheir U.S.-born ethnic counterparts. Black immigrants vote at similar levels while white immigrants participate at lesser rates compared to U.S.-born whites. Yet, in recent years, the foreign-born population appears to be a much more politically engaged cohort, demonstrating above-average levels of voter enthusiasm with turnout exceeding the general electorate. National-level polling conducted between August 16 and August 28, 2024, prior to the election, showed that roughly 97% of naturalized citizens were “definitely or probably going to vote” in the 2024 election. This is above 2020 election levels, where 86.8% of respondents cast their vote, exceeding the nearly 66% of the total electorate—the highest rate since 1900.

In the wake of the pandemic, restrictive immigration and economic and health concerns in Trump’s first term were likely key factors in an atypical 2020 election. Further, in 2024, where many of the same issues were at the forefront, final calculations of voter turnout are likely to be high. Additionally, while migrant voters constitute a small share nationally, they have sizable clout in competitive battlegrounds. For example, 14% of voters in Nevada, seven percent of voters in Georgia and five percent each in Pennsylvania and Michigan are foreign-born. The start of 2024 saw 7.4 million migrants who were likely eligible to naturalize this year and 3.5 million of them have already done so. Their total size tops the margins of victory in virtually all key swing states in the 2020 election, and projected naturalization rates resemble the prior election cycle. For example, in Georgia, the state’s total of 96,469 new citizens surpassed Biden’s roughly 12,000 margin of victory. Mostly comprising foreign-born Asians and Latinos, immigrant participation in this year’s election was expected to be decisive.

Immigrant party affiliation and voter priorities are not uniform

Still, the key issues that drove new American citizens to the voting booth are not uniform. Despite between four in 10 to six in 10 expressing no strong affiliation/not being sure with either party, immigrant voters still lean Democratic across almost all ethnic groups, except for white immigrants who are more evenly split between Democrats and Republicans. Among those who would certainly vote, the polling found they favored Kamala Harris over Trump (by approximately 55% to 41%), both nationally and with some slight variation across key swing states. Similar to the general electorate, high cost of living/inflation ranked as the top issue with immigration following closely behind. Interestingly, on social values issues, foreign-born migrants are almost twice as likely to hold conservative/very conservative views and still identify as a Democrat compared to the overall population. This is further underscored with religious views—overall, immigrant evangelicals identify less with the Republican Party compared to U.S.-born evangelicals and young individuals (ages 18 to 29) are found to be more religious and conservative on social issues than their U.S.-born counterparts.

Linked fate, the idea that policies or issues that affect one’s broader group also impact individuals, could partly suggest why: 60% of respondents believe that what affects immigrants will “strongly or to some extent” affect their own life. In previous generations, European immigrants in the 19th century who were in a pursuit of a better life, were initially dubbed as non-“white” and encountered fierce anti-immigrant rhetoric and policies. Similarly, several generations later, this modern wave of largely immigrants of color, also in pursuit of a better life, is navigating a 21st century assimilation into the American mainstream. In the past decade, Muslim travel bans, the dehumanization of African, Afro-Caribbean, and Latin American groups, anti-Asian hate crimes, and an even more hardline Trump immigration agenda aimed at legal and illegal immigrants have engulfed the political environment. What’s more, many immigrant voters come from mixed status families where one or more members of the household are undocumented while the rest hold legal status—complicating access to resources such as health care and employment. Ultimately, how migrants continue to navigate their foreign identity and new status in support of a political party varies across ethnic lines.

The policy agenda of the immigrant community

The post-election results on how all immigrant groups voted are still forthcoming, but recent surveys taken just prior to the election and the latest exit polls offer some insights.

Based on a YouGov national survey of the top issues for over roughly 43,000 immigrant voters (conducted between October 25 and October 27), the key differences across the main issues—such as the economy, abortion, immigration, education, and crime—were along gender, age, race, and ideological lines. Men were found to prioritize the economy more highly than women, whereas women ranked abortion more highly than men. However, older voters rank immigration and the economy above higher than younger voters. Similarly, conservative voters, who are likely older, were more likely to rank immigration and the economy as important relative to moderate and liberal voters. Nonetheless, across almost all policy issues and subgroups, U.S.-born voters rated these issues with greater importance than their foreign-born counterparts. Still, by contrast, across all demographic groups, migrant voters ranked crime and education as more salient than the U.S. native-born electorate.

Along racial and ethnic lines, virtually all migrant voters, regardless of political affiliation, ranked the economy and inflation among their top priorities. However, while the economy and the conflict in Gaza were the two top issues respectively among all Arabs, among Arab American Democrats, the conflict in Gaza was ranked as number one. While most Arabs in the U.S. were born here, about 68% of foreign-born Arabs are citizens.

Historically, over the past 15 years, their political support has stood at a two-to-one margin for Democrats. Nevertheless, the humanitarian crisis in Gaza and U.S. support for Israel led to a dramatic reversal—with Trump slightly leading Harris, 42% to 41% in polls ahead of the election, compared to Biden’s 59% to 35% edge in 2020. Additionally, even though expected turnout in the MENA community slipped from 80% to 63%, Michigan for example, where Biden won by 154,000 votes, houses its largest base of voters among all swing states—over 300,000. Further, the recent Democratic primary saw more than 100,000 Michigan primary voters choose “uncommitted” in protest against the administration’s handling of the war, and Arab Americans make up almost half of the populations in the cities where Biden lost to the protest vote. Taking all these factors into account, there were growing signs that Democrat support could be splintered between Trump, a third party, and/or by abstaining—and those indications proved true. The city of Dearborn, an Arab American majority city, saw Trump winning (42.4%), Harris (36.2%), and Jill Stein (18.3%)—a remarkable shift from Biden’s 68.8% to Trump’s 29.9% in the 2020 election. Further, this appears to be somewhat reflected in the latest exit polls—Trump won 60% of Michigan voters that identify as “other race” and 54% of the same cohort nationally.

Asian Americans as a racial subgroup are majority foreign born (67%), lean Democratic (42%), and contain a large number of Independents (31%), compared to the overall electorate. Partly attributable to the fact that they typically experience less campaign outreach, 27% reported not having been contacted by either political party. As a cohort, according to polling conducted in September, 77% of Asian Americans were likely to vote. Overall, they were expected to support Harris by a 38+ margin—largely along gender lines: 70% of Asian women supported Harris while only 57% of Asian men did. Additionally, while almost all ethnic groups trended in this direction, Hawaiian Natives/Pacific Islanders leaned Republican. However, the actual margin turned out to be considerably smaller (15 points in favor of Harris), according to recent election results. Conversely, Since 2020, Trump has made a five-point gain nationally among Asians and, most notably, carried a majority in Nevada (50% to 47%). Concerns over inflation, health care, and crime, coupled with diverse political views, were likely key driving factors in the broader shift. With roughly 31% of Asian Americans leaning Independent, Trump made a four-point gain with all Independents—in a race where their turnout exceeded Democrats for the first time and was equal to that of Republicans.

Within the Latino base, where migrant voters comprise 25%(as of 2018), Harris secured a majority of all Latino voters (52% to 46%), However, Trump made significant gains—largely driven by the economic anxieties of Latino men. Notching a 10-point advantage with Latino men (54% to 44%), he overcame a roughly 23-point deficit to Biden just four years prior (59% to 36%). Still, while migrants favored Harris (by a seven-point margin) and also favored a path to citizenship for undocumented immigrants (by an eight-point margin), compared to the overall Latino electorate, they still appear to hold somewhat similar views to U.S.-born Latinos. Despite having been subjects of anti-immigrant language by Trump, polling finds that a majority of both U.S.-born (67%) and foreign-born Latino voters (51%) do not feel that the president-elect is referring to them. Surprisingly, this reflects a sharp reversal of what one might expect to see regarding immigrant linked fate within the Latino community. Certain subsets appear to be prioritizing partisanship and other policy issues (largely inflation) above racial and identity politics and immigration, and to be favoring a more conservative agenda. This may partly explain Trump’s relative insulation from promoting racially prejudiced epithets, which has led to inroads with certain swaths of the Latino electorate.

What’s more, this is underscored by the variation seen across country of origin. South American and Central American immigrants are roughly twice as likely as Mexican immigrants to identify with the Republican Party. Even so, there was some expectation that the denigration of Puerto Rico as a “floating island of garbage” by a comedian at the closing Trump campaign rally could be an outlier—having seeped from politics into the cultural mainstream. Drawing swift condemnation from within the campaign, across the political aisle, and by a slew of high-profile Latino celebrities, it went beyond denouncing mostly illegal immigrants to disparaging the very core identity and cultural heritage of an entire territory. Yet, instead of a wider spillover effect among Latinos in favor of Harris, support swung the other way in Trump’s direction—helping to secure above or near-even margins in key states, such as Michigan, Nevada and North Carolina.

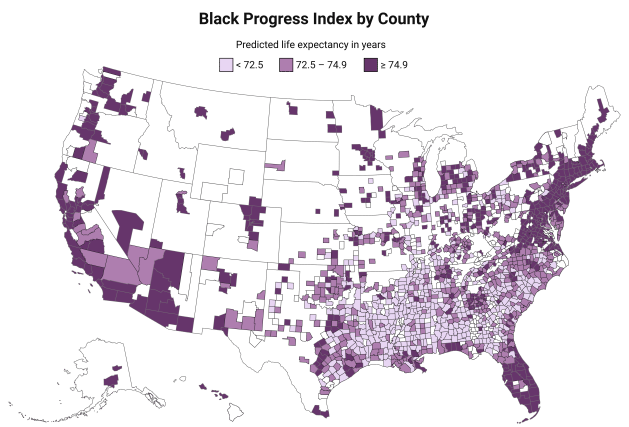

Among Black and white immigrants, there is somewhat limited nationally representative data on their voter priorities compared to other demographics. However, evidence suggests that Black immigrants, primarily from the African and Caribbean regions, and roughly 10% of the overall Black population,tend to vote for Democrats, similarly to U.S.-born Blacks. However, Black migrants rank the economy and immigration as more important than native-born Blacks and also rank the economy higher than all other migrant and non-migrant groups—suggesting that Black immigrants and more specifically Black immigrant men may be one of the most economically vulnerable of all the cohorts. The trends in the polls to some extent suggest why. Trump’s relative gains with Blacks overall (currently at roughly 13% support) was mostly driven by disaffected Black men—particularly in Midwest states such as Wisconsin, with large swaths of blue-collar workers now supporting him.Seventy eight percent of Black men supported Harris, compared to 80% for Biden in 2020, Further, an analysis of Black male voters shows that while roughly 11% of U.S.-born Black men voted for Trump in 2020, an even higher number of foreign-born Black men (30%) did so. This reveals how differing socio-cultural experiences formed in one’s home country, distinct from the U.S., and coupled with the challenges of assimilating into a foreign country, can influence voter choice.

On the other hand, white immigrant voters (roughly three percent of the total white electorate as of 2018), in contrast to other racial groups, exhibited more of an even split between the two parties. Still, while they rank immigration and abortionhigher than all other migrant racial cohorts, they rank the economy/inflation and immigration as significantly less important than would U.S.-born white voters. Based on the latest exit polls, there did not appear to be a significant change in the white electorate compared to the previous 2020 election—white men voted at roughly the same levels of support for Trump with a slight softening of support among white women.

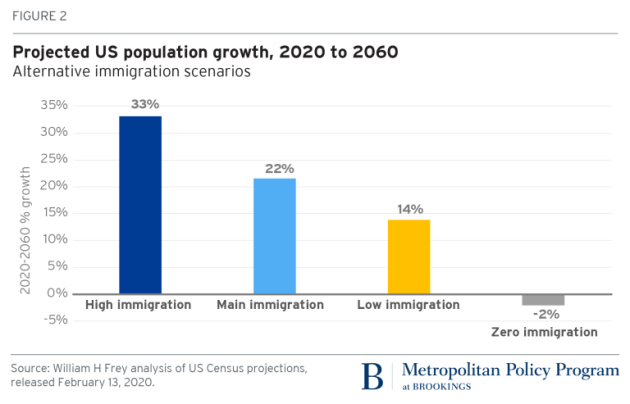

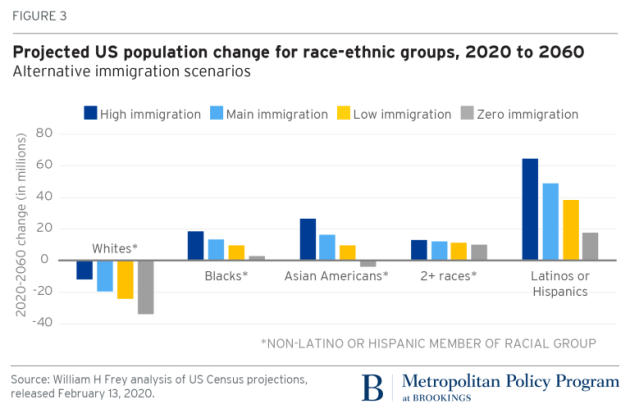

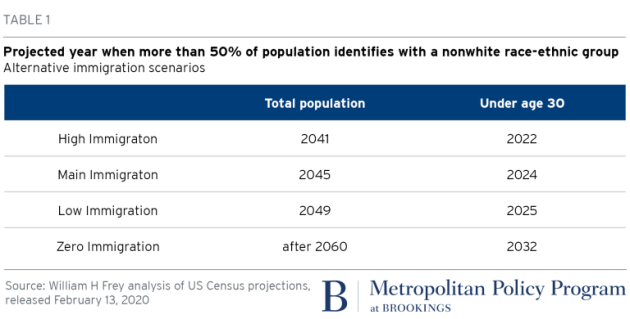

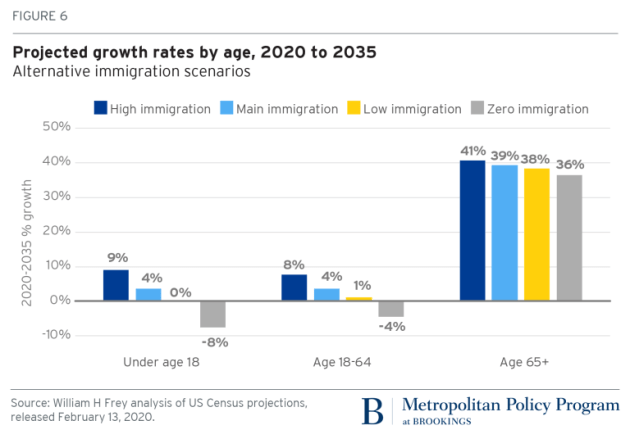

Ultimately, given migrants’ diverse political views and electoral sway in this tight race, both the incoming administration and future campaigns will need to take stock of their concerns. With rising interracial marriages and mixed-race subgroups, not only is international migration estimated to outpace U.S.-born population growth by 2060, but the country is also expected to be majority minority by 2045, more closely resembling its foreign-born makeup of voters. While the president-elect did not secure a majority of migrant voters, he was, with a largely national economic message, able to make significant enough gains within a fractured Democratic coalition. Conversely, the Harris campaign struggled to distance itself from the economic issue saddling the Biden administration, and underperformed among the Democratic base.

Still, despite the deep political rift currently dividing the nation, the country is still inextricably linked to one common shared identity—America is a nation of immigrants, with longer-term descendants of past generations and more recent newcomers. And the majority of its inhabitants continue to pursue the American dream—seeking to make a better life for themselves, their families, and their communities. It is therefore incumbent on the next president to work with Republicans and Democrats to unify the country and enact a set of policies that not only caters to the diverse needs and everyday concerns of the immigrant community across the aisle, but also of the entire country at large. It remains to be seen how this will unfold in the coming weeks, months, and years ahead. But what is certain is that as the country’s racial dynamics continue to evolve, new Americans, like their predecessors from past generations, will continue to play a critical role in U.S. politics for years to come.

Source: America’s immigrant voters and the 2024 presidential election