Semowo: It’s Black History Month. Let’s Move Inclusion Beyond Visibility

2025/02/10 Leave a comment

Nice to see academics interested in citizenship and the various study guides over the year that overall indicate progress. However, policy makers have to decide how much to include in a guide, how much detail on particular groups and history, keeping in mind the need for simple language, the audience of new Canadians and related needs of being concise.

As well as the balance between portraying a positive image of Canada to those becoming citizens while acknowledging less positive historical and current issues.

Suspect that many groups could make similar critiques without acknowledging the need for balance and perspective.

Unclear that the revised guide, under preparation under at least four IRCC Liberal ministers would equally meet Semowo’s criteria for inclusion. And of course, there is no formal citizenship education under the settlement program, an ongoing gap:

A Canada where Blackness was overlooked

Since 1947, the federal government has published citizenship study guides to help new immigrants prepare for citizenship tests.

These guides are more than bureaucratic texts; they frame Canada’s shared identity and values for newcomers. Yet for much of the 20th century, they presented a Canada relatively devoid of Blackness.

Canada’s first citizenship study guide failed to mention Black Canadians at all. Instead, the guide celebrated British and French heritage while paying scant attention to Indigenous Peoples and other racialized communities.

Subsequent guides beginning in 1963 included either an image, text or both describing people of African descent. However, their inclusion was sparse and narrowly focused, signalling that Blackness is peripheral to Canadian identity.

The 1995 study guide entitled A Look at Canada briefly acknowledged Black Loyalists but overlooked their struggles in Nova Scotia, where many were denied the land they were promised.

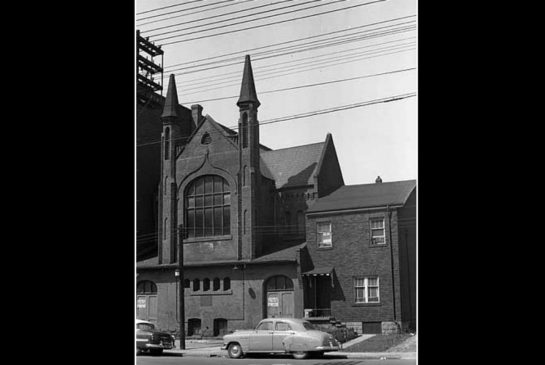

Africville, a Black community razed in the 1960s, was notably absent. Indeed, many Canadians remain unaware of Africville or the civil rights activist Viola Desmond, whose defiance against segregation in 1946 is often overshadowed by more well-known American figures, such as Rosa Parks.

This lack of visibility in official narratives not only disconnects Black Canadians from their own history but also perpetuates the myth that systemic anti-Black racism is solely a U.S. problem.

A recent study guide from 2009 titled Discover Canada presented a few notable figures, such as the athlete Marjorie Turner-Bailey, abolitionist publisher Mary Ann Shadd Cary and Victoria Cross recipient able seaman William Hall.

These provide valuable recognition of Black Canadians’ historical presence and struggles.

However, their inclusion follows a pattern of narrow representation, where Black history is framed primarily through individual achievements rather than part of a broader discussion on systemic barriers.

While the guide, a version of which is still in use today, acknowledged slavery, abolition and Black migration, it does not deeply engage with ongoing racial inequities in Canada, such as economic disparities and segregation. This tokenization mirrors patterns in real life.

Black Canadians are often called upon to represent diversity in workplaces or public events, but these gestures rarely challenge the structures that perpetuate inequality.

Similarly, the citizenship study guides’ brief mentions of Black Canadians create the impression that inclusion has been achieved, leaving deeper systemic issues unacknowledged and unaddressed. 2009’s Discover Canada praised the bravery of Black soldiers in both World Wars yet omitted the fact that many were initially denied the opportunity to serve in the military.

Minimalization also occurs when Blackness is reduced to narratives of struggle. While it is vital to honour the fight against slavery and segregation, the guides rarely highlight Black joy and innovation.

This framing not only flattens the complexity of Black experiences but also risks perpetuating stereotypes that limit how Black Canadians are perceived.

‘Selective inclusion’

One of the most revealing insights from the citizenship guides is how they reflect selective inclusion. In 2009’s Discover Canada, for instance, Canadian multiculturalism is celebrated as a cornerstone of national identity.

Yet the guide devotes far more space to Canadians of European descent, reinforcing a hierarchy of who is most celebrated in the national story.

This reflects a broader reality: Black Canadians are often welcomed in limited contexts, such as sports and entertainment, while facing systemic exclusion in areas like politics, corporate leadership and academia. For example, while Canada has celebrated athletes like Donovan Bailey and acclaimed writers like Esi Edugyan, Black representation in federal politics remains disproportionately low.

These issues — of selective inclusion and systemic exclusion — are especially important to highlight now because the dismantling of DEI policies in the U.S. can have a chilling effect across North America: conversations about systemic racism can be labelled as divisive, and efforts to address historical exclusions may be dismissed as unnecessary.

If Canada is to uphold its commitment to diversity, it must critically examine how its own narratives have shaped belonging.

Here in Canada, the federal Conservative Party leaders have been attacking diversity, equity and inclusion efforts. Within progressive circles, our DEI efforts often face criticism — that is, more about optics than meaningful change.

‘Inclusion must go beyond visibility’

As we reflect on Black History Month, our citizenship study guides offer an important lesson: inclusion must go beyond visibility.

It is not enough to name a few figures or reference historic injustices without addressing the reality of anti-Black racism in Canada today — a fact newcomers to Canada not only deserve, but need, to know.

A meaningful way forward would be to integrate Black history more fully into the newcomer education curriculum, ensuring that stories like Africville and Viola Desmond’s trial are seen as essential parts of Canadian history, not as footnotes.

Black History Month is also a reminder that diversity is not just about celebrating achievements but about creating systems that allow all Canadians to thrive.

Citizenship, in its fullest sense, means belonging—not just in the abstract but in the lived experience of equity, recognition and opportunity.

The evolution of the citizenship guides shows progress but also highlights how much work remains.

As we move forward, we must commit to telling the whole story of Canada — a story where Blackness is not erased, tokenized or selectively included, but embraced as integral to the fabric of this nation

Source: It’s Black History Month. Let’s Move Inclusion Beyond Visibility