Australia: A major multiculturalism review has recommended bold reforms. How far is the government prepared to go?

2024/07/26 Leave a comment

Jakabowicz on the review:

A year ago, the government instigated an independent review of the national multicultural framework.

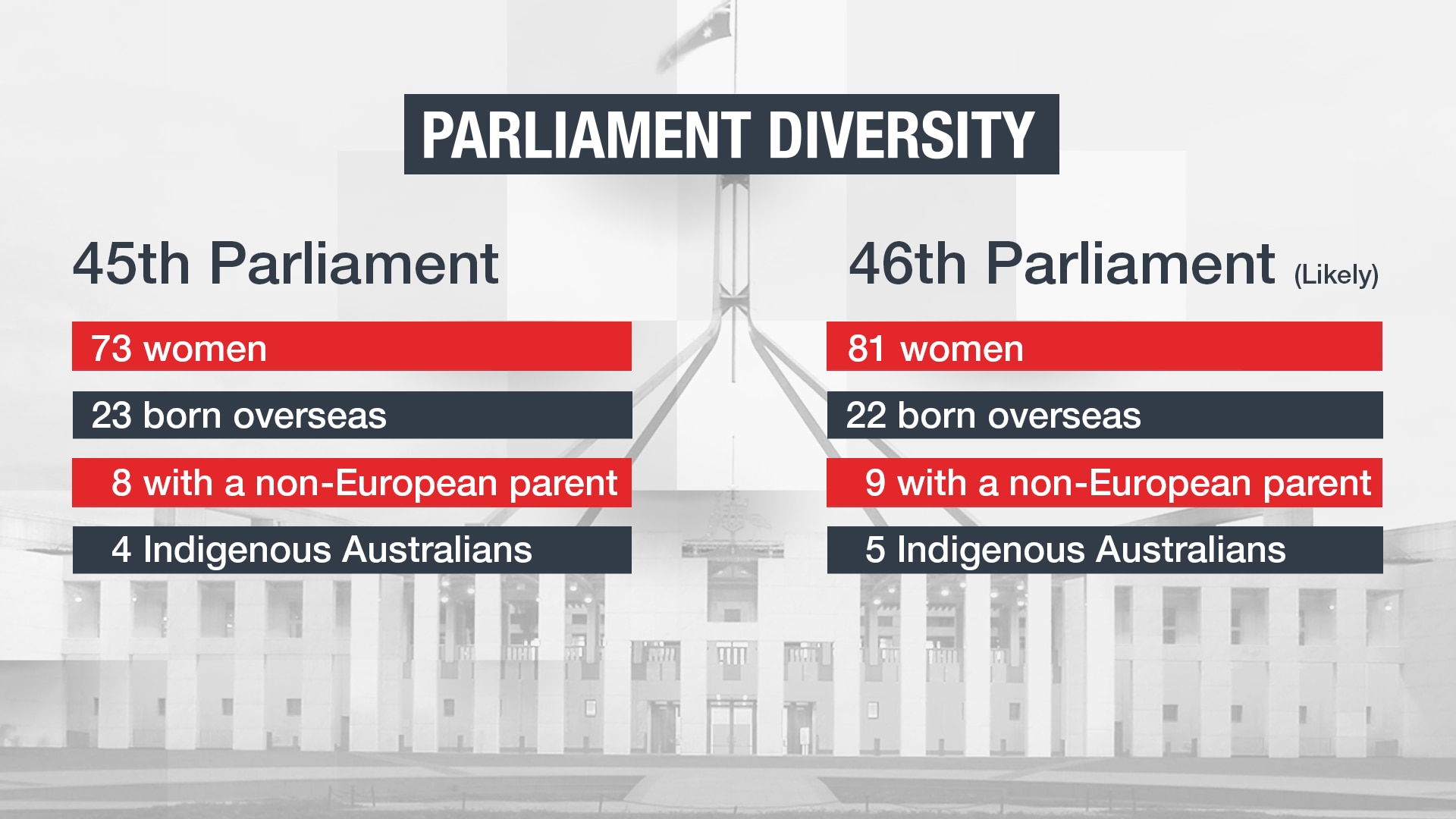

As more than half of Australia’s population is either born overseas or has one parent who was, this policy is important. It underpins how multiculturalism works in almost every part of life. It aims to ensure equity and inclusion for people from minority groups, and attempts to whittle away at structural racism.

Now the review report has been released. This comes against a backdrop of growing antisemitism and Islamophobia in Australia, as well as the fallout from the failed Voice to Parliament referendum and the vicious racism many communities experienced during the COVID crisis.

The report includes 29 recommendations for improving Australia’s multicultural society. The government has committed $100 million over the next four years to implement the recommendations, though it is still working through the details and timeline. Here’s what it found.

Some of the recommendations are symbolic and have appeared in every multicultural review over the past 50 years. But other recommendations are far more concrete.

Firstly, it suggests there be a federal Multicultural Commission (a proposal the Greens have had on the parliamentary agenda without Labor support for some years). This body would be empowered to provide leadership on multicultural issues, hold opponents of human rights to account, and promote close collaboration between stakeholders at all levels.

Secondly, the panel proposes breaking up the Department of Home Affairs. This would be an attempt to reverse the surveillance and punishment approach that many believe the department to have towards migrants, refugees and some ethnic groups.

Instead, it suggests a new-look, nation-building, Cabinet-level Department of Multicultural Affairs, Immigration and Citizenship.

And from a policy perspective, the report recommends:

- better ways to protect people’s languages

- a citizenship process that is less about learning cricket scores and more about appreciating diversity and the importance of mutual respect

- diversifying our media sector so it more effectively reflects and involves our minority communities

- and ensuring the arts and sports sectors are spaces for intercultural collaboration and cooperation.

Overall, the report shows how marginal multicultural affairs have become in government – these ideas would go a long way toward refocusing the government’s attention where it is needed.

Why was this review needed?

The review was tasked with assessing how effective Australia’s institutions, laws and policy settings are at supporting a multicultural nation, particularly one that’s changing rapidly. This included looking at the challenges of refugee and immigrant settlement and integration, as well as the impact of world events on Australia’s multicultural society.

There’s also an economic element. The review looked at how we can ensure the wide-ranging talents of Australia’s residents are fully harnessed for personal and broader societal benefit.

These questions point to the need to bring together political, economic, cultural and social priorities in our government programs and policies. They also recognise the deeper challenges of racism, social marginalisation and isolation, which are often compounded by other factors, such as age, gender, class, health and disability.

These are not new questions. What is new is the recommendation for a strategy to engage in a sustained and interconnected way with the causes and consequences of our current failures. It is very unusual for a government to ask a review to do this.

The findings also bring together the perspectives and insights that many advocates in this space have long championed, but which have been swept aside and neglected for over two decades.

Importantly, the report stresses that a national commitment to multiculturalism demands bipartisanship.

I made an argument for a research strategy element in the review in 2023, and was later commissioned to develop a paper on research and data for a multicultural Australia.

The panel has now recommended that a national multicultural research agenda be developed by the new Multicultural Commission, taking account of my recommendations.

What will the government do?

There is still a long row to hoe – none of the recommendations have been publicly accepted (nor dismissed) by the government, and as yet no specific resources have been committed (despite the $100 million commitment overall). Significant action, however, is likely over the coming months and in future budgets.

While it is unlikely Home Affairs will be broken up immediately, some major moves to upgrade the capacity of the public service to deliver on the government’s commitments are likely. The courage of the government to advance these priorities in the election will depend in part on public reactions to the report and its implementation, as well as the stance of the Opposition.

Will the panel’s extensive work improve cohesion, enable better community relations, and unleash the social and economic benefits of a more collaborative society? The first test will be in how a proposed Multicultural Commission would be structured, led and resourced. We may not have long to wait.