Every few years, the phrase “birth tourism” seems to re-emerge in the news cycle. It refers to non-residents giving birth outside of their home country to gain citizenship and, occasionally, health care for their newborns. Birth tourism isn’t illegal in Canada, but it’s a fraught issue that tends to kick up discussions about who deserves access to the country’s health care system, especially in times of low bandwidth. Like now.

Simrit Brar, an OB-GYN at Calgary’s Foothills Medical Centre, is one of many Canadian doctors who claim to have noticed a recent spike in the number of birth tourists arriving out west. But because that data isn’t routinely collected by hospitals, it’s been impossible to understand the real scope of the issue. Last year, Brar was part of a research team that conducted the country’s first in-depth study on birth tourism in Alberta, and this year—for the first time—the Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada is forming a working group to study its impact country-wide. Here, Brar reveals what we know so far.

What prompted you to study birth tourism?

Anecdotally, my colleagues and I noticed an increase in the number of cases we were seeing in Calgary hospitals over the past decade or so, but it’s been difficult to draw any real conclusions about the motivations, health outcomes or financial situations of birth tourists. We know they don’t have Canadian health coverage, but sometimes they have their own private insurance plans that reimburse their care costs. Canadian doctors were struggling to provide timely care for our baseline population even before the pandemic. Birth tourism is far from the only factor straining the health care system, but we knew it was an additional cost, and that we didn’t have the data to understand it. We saw an opportunity.

So how do birth tourists differ from other uninsured pre-natal patients in Canada?

Based on our research, birth tourists are typically middle to upper-middle class, with the means to support themselves while in Canada. The people we looked at weren’t necessarily disadvantaged. I want to be clear: refugees, asylum seekers, undocumented migrants and those in similarly precarious situations—like patients whose provincial health insurance has lapsed, for whatever reason—are not birth tourists. A birth tourist makes the conscious decision to travel and give birth here, and generally they have no intention to stay. Piling everyone under the same umbrella misses those crucial nuances and prevents us from making informed decisions, both at the policy level and in day-to-day care.

If you’re right that there’s been an uptick in birth tourism, what do you think is causing it?

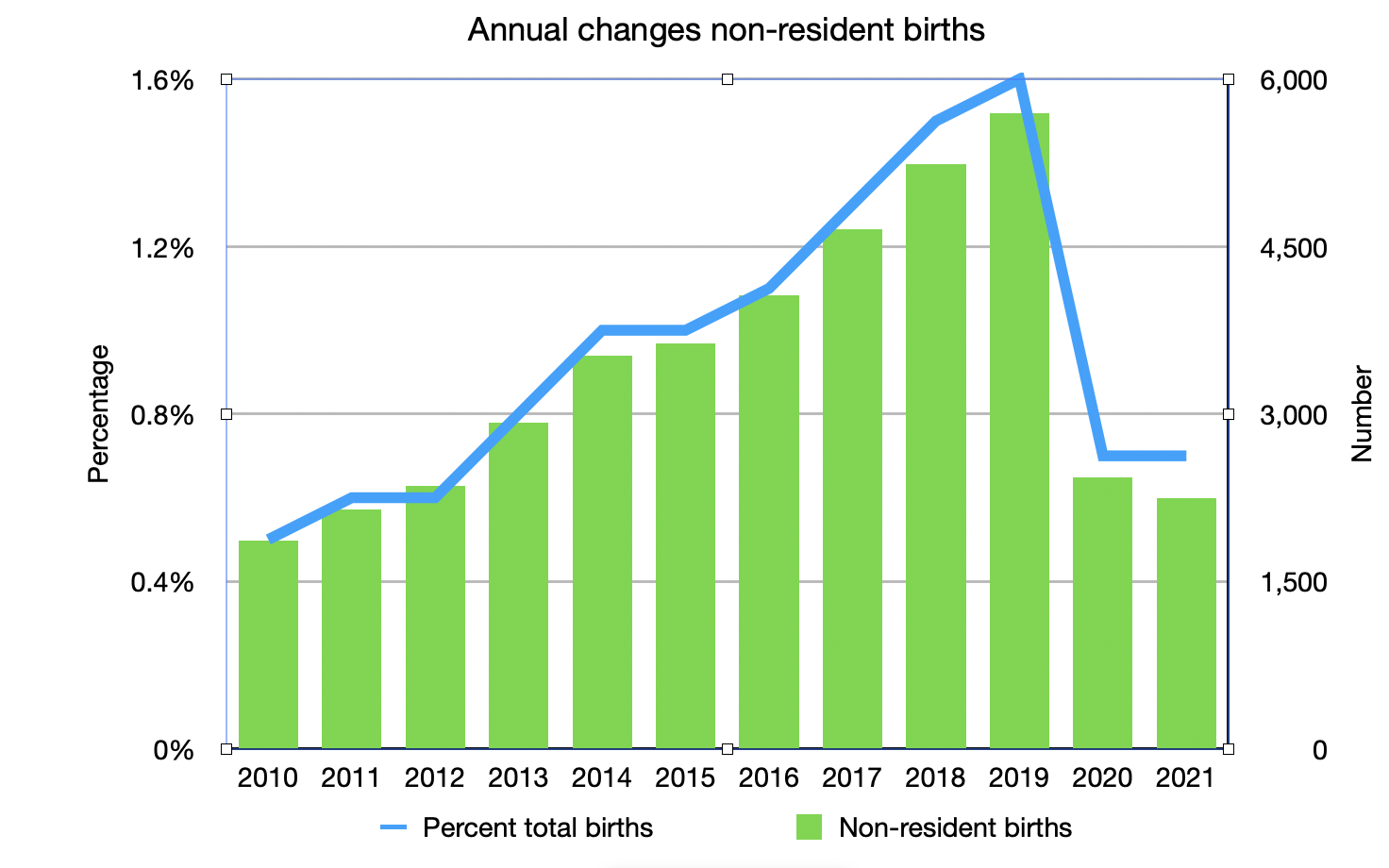

It’s hard to say. We saw it slow a bit during the pandemic, given travel restrictions, and now it seems to be picking up again. I think the availability of information via social media is one factor; that spreads awareness that this is even an option. There are also companies that specialize in facilitating the birth-tourism process. They seem to market themselves online and through word-of-mouth.

What did your study reveal about why birth tourists are coming to Alberta? And where are they typically coming from?

About a quarter came from Nigeria, probably because there’s an established Nigerian community in the Calgary region. Birth tourists tend to go where they have friends or family. Smaller portions came from the Middle East, China, India and Mexico. The vast majority arrived with tourist visas, and based on our interviews, they weren’t facing particularly precarious situations back home. Again, I can only speak to the population we studied, but in general, these are women with resources.

What were they seeking?

That majority said their goal was to get Canadian citizenship for their newborns. Many saw it as an easier route to citizenship for their kids than applying through the typical process. Others either wouldn’t tell us their motivations or said they wanted to somehow benefit from quality Canadian health care.

When birth tourists get off their flights, what is the extent of their health needs?

Many travel here late in their pregnancies and arrive close to 38 weeks, which can lead to complications. I’ve seen patients with pre-existing high blood pressure get off a plane with numbers that are through the roof. Often, they’ll show up at a family doctor’s office, who sends an urgent hospital referral. I’ve also seen patients with pre-term twins literally get off a plane and go straight to an emergency room to deliver. Even somebody who might be otherwise low risk but shows up with no medical imaging or other records of pre-natal testing can have adverse birth outcomes, like unchecked pre-eclampsia and gestational diabetes. These aren’t isolated incidents, either.

When you crunched the numbers, what was the total cost incurred by the province to take care of these people?

For the 102 people we studied, the total amount owed to Alberta’s health care system was $649,000. That may not sound like a lot, but this is just one small study. If you were to add up the costs across Canada, you would end up with a significant amount. I also want to emphasize that this is not just about money. Canada’s health care system isn’t like the States’, which is not only fee-for-service but has a much larger population—and accordingly a larger number of health care providers. Our public system has a finite number of doctors, nurses, and anesthetists. Every province has a lengthy surgical waitlist, and we’re struggling to care for insured patients. So even if a birth tourist does pay their bill, if we allow people who have the opportunity to pay to preferentially access beds (and finite human resources), that displaces people here.

Have any solutions been proposed? If birth tourism isn’t illegal, but it is draining resources, how do we move forward?

We’ve discussed developing a standard charge and different systems for collecting it. In Calgary, we’ve established a central triage system, where patients identified as birth tourists are charged an upfront deposit of $15,000 to cover physicians’ fees. They’re refunded whatever part of that doesn’t end up being used. It’s the only measure of its kind in Canada. Transparently, that number is meant to be a deterrent.

Conversations on this topic occasionally lean toward a xenophobic—and even racist—lens, particularly in the States. Media coverage can sometimes paint pregnant women of colour as a national security threat. What are the biggest misconceptions about this issue?

I say this as a woman of colour: in my opinion, this is not a race issue. It’s a social-structure issue. It’s about access to care. When you have money and you have the ability to get on a plane and choose where to go, your options are different. The issue here is the use of a limited public health care resource. It’s about what it means for patients in disadvantaged communities here. Birth tourists have the ability to choose where they want to go, whereas somebody in a marginalized community may not have that ability. If we open the floodgates, we are further limiting people with very limited options.

Birth tourism highlights some really interesting philosophical tension around the Canadian health care system, the spirit of which is to make sure everyone is taken care of. Here, we see the limits of that thinking. Has studying birth tourism changed your perspective?

You hit the nail on the head. I would love nothing more than to have unlimited resources and help anyone and everyone. That would be dreamland. I would love to not have to fight to get things done. And to be clear, I would never deny care to a patient. But the reality is that we operate within a finite system, and even though the conversations around the allocation of those resources are difficult and complex, we have to have them. I would identify wanting to help as many people as possible, and in the best way possible, as a fundamentally Canadian value. But the system is too strained for us to ignore these questions.