It’s Time to Abolish the Absurd (and Slightly Racist) Concept of “Visible Minorities”

2022/02/23 Leave a comment

Apart from some of the hyperbole, without some system of classification, it becomes difficult if not impossible to assess socioeconomic and political outcomes and thus inclusivity. Visible minorities, like Indigenous peoples, have disaggregated data which is increasingly more widespread (e.g., public service).

It is one thing to criticize how activist use the data, another to argue for not collecting and analyzing the data.

In my analysis of public service employment equity, I find many activists have not taken a serious look at the data in making their case for change (see Will the removal of the Canadian citizenship preference in the public service make a difference?, where I provide occupational and group breakdowns, which interestingly, for example, that Blacks in EX positions were under-represented to a lessor degree than South Asians and Chinese).

But data, in highlighting similarities and differences, provides a frame under which one can analyse and hopefully understand some of the underlying reasons for those differences, as Skuterud does (some of which may reflect historically patterns of discrimination).

As to repealing the Employment Equity Act, hard to see any government doing so or abandoning the collection of disaggregated data minority groups. But Woolley’s point of shifting the focus towards socioeconomic measures of disadvantage is not incompatible with attention to minority groups as a means of analyzing and assessing differences in outcomes.

No other country in the world divides itself along racial lines as we do in Canada. According to federal legislation, our country consists of three distinct race groups: Indigenous people, whites and everybody else. Members of this final catch-all category are officially deemed “visible minorities” and defined in law as “persons, other than Aboriginal people, who are non-Caucasian in race or non-white in colour.” Canadians can either be native, white or non-white. How’s that for inclusivity?

The term “visible minority” was invented in 1975 by black activist Kay Livingstone, founder of the Canadian Negro Women’s Association, as the means to unite disparate immigrant groups at a time when Canada was overwhelmingly Caucasian. By 1984, the phrase had gained sufficient currency to play a starring role in the final report of Judge Rosalie Silberman Abella’s Commission on Equality in Employment, and was later enshrined in law via the federal Employment Equity Act of 1986. This law requires all public and private sector employers to improve the job prospects for visible minorities, women, Aboriginals and people with disabilities through the elimination of barriers and creation of various “special measures,” such as targeted hiring. Today, this dichotomy of “able-bodied white males versus everyone else” still forms the basis for myriad policies and regulations meant to impose greater diversity in the workplace and throughout society.

While Abella’s report was instrumental in cementing the concept of visible minorities in federal law, she recognized at the time that lumping everyone who isn’t white into a single generic category could create complications. “To combine all non-whites together as visible minorities for the purpose of devising systems to improve their equitable participation, without making distinctions to assist those groups in particular need, may deflect attention from where the problems are greatest,” Abella wrote. That said, the future appointee to the Supreme Court of Canada figured a solution would eventually appear. “At present,” she observed, “data available from Statistics Canada are not sufficiently refined by race…to make determinative judgements as to which visible minorities appear not to be in need of employment equity programs.” (Emphasis in original.)

The term ‘visible minority’ was invented in 1975 by black activist Kay Livingstone, founder of the Canadian Negro Women’s Association, as the means to unite disparate immigrant groups at a time when Canada was overwhelmingly Caucasian.Tweet

Nearly four decades later, Canada no longer suffers from an absence of race-based data. We are, in fact, inundated with it. And the evidence arising from this flood of racially-focused statistical work is clear and unambiguous: the entire concept of visible minorities – along with the superstructure of policies and laws that support it – makes no sense in our pluralistic 21st century Canada. It’s time to abolish this outdated, imprecise and subtly racist idea.

The Data Speak Volumes

Among the Trudeau government’s many indulgences to the cause of social justice has been the creation of the Centre for Gender, Diversity and Inclusion Statistics at Statistics Canada. Reports from this branch of our national statistical agency focus almost exclusively on dividing Canadian society up into ever-smaller slices by race, gender and other attributes (a recent effort tracks the educational attainment of bisexual people) and frequently serve as fodder for activists intent on claiming Canada is rife with systemic discrimination and racism whenever a gap is identified. Yet a gap-filled study released last month examining how various racial groups within the visible minority category are doing in Canada’s labour market received surprisingly little attention from the media or within activist circles. This may be because most of the gaps it reveals aren’t the sort that give rise to claims of racism.

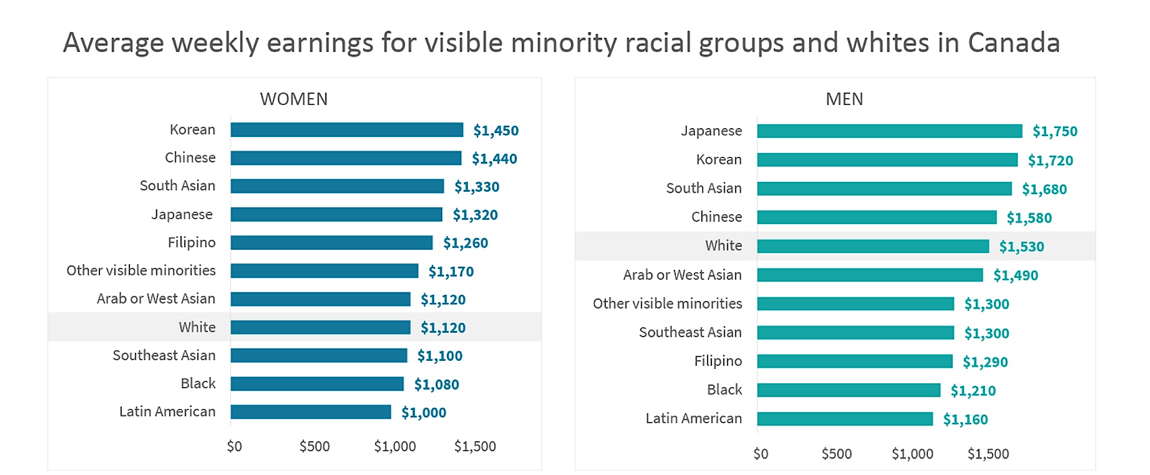

The results of the study by Statcan researchers Theresa Qiu and Grant Schellenberg will come as a shock to anyone expecting to find whites sitting atop the labour market. Rather, the best earners are Canadian-born Japanese males, who earn an average $1,750 per week. This compares to $1,530 earned by white men. Chinese, Korean and South Asian (from India, Pakistan etc.) males also take home more than whites. Among women, whites are out-earned by a majority of groups within the visible minority category, including Chinese, Korean, Japanese, Filipino, South Asian and Southeast Asian (from Vietnam, Thailand etc.). At $1,450 per week, the average Canadian-born Korean woman earns $330 more per week than the average white woman. For both men and women, the two lowest-earning categories are blacks and Latin Americans.

Source: The weekly earnings of Canadian-born individuals in designated minority and White categories in the mind-2010s by Theresa Qiu and Grant Schellenberg, Statistics Canada, 2022

While clearly contrary to current narratives declaring all of North America to be a bastion of white supremacy, these findings are not unusual for either side of the border. The latest American data on full-time workers similarly shows Asian men to be the highest income earners among full-time workers in the U.S., at US$1,457 per week, exceeding the US$1,108 per year earned by white men.

Asian women also out-earn American white women, by nearly US$200 per week. Other data from the Pew Research Center on household income point to South Asian-born families as the top earners in the U.S. by a substantial margin. It bears notice that Qiu and Schellenberg wisely avoid confusing the immigrant experience, which entails numerous challenges of language, culture and credentials, with that of being a visible minority in Canada. They do so by focusing only on Canadian-born visible minorities aged 25 to 45 (that is, young second-generation immigrants) and comparing them with similarly situated whites.

Source: Facts on U.S. Immigrants, 2018 by Pew Research Center, 2020

The researchers further refined their work by adjusting for university education and other demographic characteristics. Here South Asian men were found to do significantly better than white men. Blacks and Latin Americans again did worse. Among women, several visible minority categories statistically outperformed whites, and no group – not even black women – did worse.

The results illustrate the pre-eminence of a university education in explaining job market success. ‘Nearly three-quarters of Canadian-born Chinese women have a university degree,’ marvels Skuterud. ‘That’s amazing.’Tweet

A Good News Story for Many, but not All

Do such results bolster the loud and widespread narrative that Canada is a systemically racist country? According to one labour market expert, such a declaration is impossible to make despite the large gaps in performance seen across the visible minority subgroups. “There is absolutely no way to infer any conclusion from this data about whether there is racial discrimination in the labour market,” says Mikal Skuterud, an economist at the University of Waterloo, in an interview. “Some groups are clearly outperforming whites, but no one would interpret that as evidence of discrimination against whites, or for Canadians with Chinese, Korean or Japanese ancestry.”

To Skuterud, the fact many Asian groups outperform the rest of Canadian society is a “good news story” since these segments comprise a large and growing share of Canada’s current immigration intake; this bodes well for the integration of future immigrants from these countries in coming years. The results also illustrate the pre-eminence of a university education in explaining job market success, as the strong performance across many Asian groups is closely linked to their high rates of university completion. “Nearly three-quarters of Canadian-born Chinese women have a university degree,” marvels Skuterud. “That’s amazing.”

Skuterud is troubled, however, by the poor results for blacks and Latin Americans, something that also appears in his own research. It is conceivable, he notes, that such persistent gaps are the result of labour market discrimination specifically targeted towards certain groups, rather than across the entire visible minority population. Such a possibility requires further investigation, he says. There are, however, numerous other explanations for this phenomenon, including broader cultural or socioeconomic factors not captured by the recent study. For example, another Statcan report found the rate of lone parenthood, a factor strongly associated with poverty and poor educational outcomes, is nearly three times more common among black mothers than in Canadian society at large. “Black immigrant populations stand out for their prevalence of lone mothers compared to the rest of the Canadian population,” the 2020 report observed. It is hard to imagine this not being a significant factor when it comes to the jobs market.

Taken at the broadest level, Qiu and Schellenberg’s results can be seen as a thorough dismantling of Livingstone’s nearly half-century-old claim that the term “visible minority” describes a single coherent category unified by the lack of whiteness of its members. This “group” now includes both the highest and lowest-earning racial categories in Canada, a fact that stretches diversity to the point of absurdity. The exceptional outcomes for Canadian-born Asian men and women strongly suggest factors other than discrimination – primarily education, family and socioeconomic status – are driving the divergence in earnings across race. And if skin colour is not a useful explanation for performance in the labour market, using it as a basis to set employment targets, as is the case within the federal public service, becomes a perversion of good policy.

“Did it ever make any sense?”

In a column in the Globe and Mail nearly a decade ago, Carleton University economist Frances Woolley declared that, “There is something almost racist about the assumption that whites are the standard against which anyone else is noticeably, visibly different.” Her opinion hasn’t changed much since then. Asked today if it still makes sense for Canada to enshrine the concept of visible minority in law given the recent Statcan results, she shoots back, “Did it ever make any sense?”

The current system, Woolley observes in an interview, is entirely arbitrary in its binary conception of people as either white or not. “The word white is very imprecise,” she notes. According to Statcan, for example, Greek Canadians are European and part of the dominant white, mainstream society. Yet anyone who traces their roots to Turkey, right next door, is considered West Asian and hence a visible minority. As a result, one neighbour is eligible for special measures and one is not. Plus, “a lot of people who consider themselves white – such as Lebanese Christians – are identified as visible minorities by the Census,” Woolley adds. The U.S. classifies most Arab ethnicities as Caucasian.

The rise of individuals with multiple or competing racial identities due to the rapid growth in interracial marriages further complicates the notion of colour-coding Canada’s population. The share of mixed-race relationships has more than doubled over the past decade and now comprises 7.3 percent of all marriages and common-law relationships in this country. As these couples have children, it will get progressively more difficult to sort Canadians into separate racial baskets of white and non-white. (Aka oppressors and victims.)

Then there is the issue of how nearly everyone can end up being considered part of a minority group and thus deserving of special treatment. Visible minorities currently comprise 22 percent of Canada’s total population, based on 2016 Census data, a figure that will undoubtedly rise with the release of updated 2021 Census data later this year. In some urban centres such as Surrey, B.C. or Markham, Ontario, visible minorities already constitute a clear majority. Indigenous people make up another 5 percent of Canada and people with disabilities are estimated at 22 percent. Finally, women represent 50 percent of all other groups. “Designated groups [under the Employment Equity Act] are now an overwhelming majority in the labour market,” says Woolley. “Surely we can all agree that’s problematic.”

The only slice of the Canadian population not offered special treatment under this framework is that of able-bodied white men. Yet the notion that white men stand astride the Canadian economy like a Colossus is both outdated and unfair. As Qiu and Schellenberg reveal, white men have one of the lowest rates of university completion across all racial groups, at 24 percent. This is significantly lower than black women at 36 percent, and only slightly higher than black men, at 20 percent. Given the importance of education to future earnings, low rates of university education in any racial group should be a troubling matter for fair-minded policy-makers.

Whites, both male and female, are also much more likely to live outside urban areas, another factor Qiu and Schellenberg found to be associated with lower earnings. And as a group, whites are noticeably older than those within the various visible minority subcategories. All of which suggests whites, and in particular white men, are likely to face strong headwinds in the future. They may, in fact, be more deserving of government attention than many other identity categories. “The real question,” insists Woolley, “is how can we make the system fair for everyone, not just designated groups.”

A Better Way Than Racializing Everything

Faced with the obvious folly of the entire visible minority concept, the progressive activist community appears focused on changes of nomenclature rather than substance. Linguistic constructs such as BIPOC or “racialized individuals” are more commonly used these days than the term visible minority. But such changes raise more questions than they answer. Consider BIPOC, an imported American acronym for Black, Indigenous and People of Colour. But aren’t black people also people of colour? And if so, why include them twice? As for “racialized,” the word appears derived from an invented verb: to racialize. But that suggests identity is dependant on the views of others, rather than a permanent, self-conceived state.

Any real commitment to tackling the inconsistencies inherent to the uniquely Canadian concept of visible minority must do more than just fiddle with terminology. In its 2020 Fall Economic Statement, the Trudeau government announced plans to review and modernize the Employment Equity Act. The most attractive solution would be to scrap it altogether and recuse the federal government from any further involvement in private-sector hiring practices. A competitive job market driven by need and focused on merit has no apparent problems hiring well-qualified candidates regardless of race, as the Asian experience ample demonstrates. Yet such a hands-off, market-driven and colour-blind approach seems extremely unlikely.

In the absence of simple economic logic, one immediate remedy would be to stop using whites as the reference group. Given evidence that whites no longer command the highest wages or best jobs, it makes more sense to shift to a simple Canadian average in future Statcan reports. This would resolve Woolley’s complaint about the implicit racism of making whites the standard by which all others are measured. “If you tested everyone relative to the Canadian average rather than whoever is considered ’white,’ I think that would be a good thing,” she says. “It would mean we are no longer taking the white experience as aspirational, or the norm.”

Achieving a colour-blind labour market would require shifting away from our current preoccupation with race to focus on more important factors. Poverty would be a good place to start.Tweet

Then again, any system that continues to examine performance by race, regardless of the comparator, perpetuates the fiction that racial identity is the ne plus ultra of the job market – if not personhood itself. While a fixation on skin colour has lately come to define public policy in many troubling ways, doing so embeds the concept that Canada is a collection of disparate racial groups constantly in conflict with one another. It would be far healthier for society to simply accept that we all share a common identity as members of a pluralistic Canada. Full stop.

Plenty of evidence suggests Canadians don’t care nearly as much about race as the media or political classes constantly claim they do. Consider the 2019 federal election, which featured those potentially damning images of a young Justin Trudeau in blackface. Most Canadians simply shrugged it off. As author Christopher Dornan observed in his book recapping the election, “The issue of racism – overt and latent, deliberate and unwitting, systemic and extrinsic – simply did not take hold in the election discourse.”

Achieving a colour-blind labour market would require shifting away from a preoccupation with race to focus on more important factors. Poverty would be a good place to start. Says Woolley, “If your family income is a million dollars a year and both your parents have PhDs, then the colour of your skin doesn’t matter. The same goes if you grew up in foster care and have struggled all your life.” Disadvantage and hardship can occur in families of all races and ethnicities. Yet under Canada’s visible minority framework, needy individuals can be ignored while others with a different skin tone get a leg-up they don’t deserve. “We need a fair process and fair procedures,” Woolley asserts.

A fairer system, Woolley says, should “try to get at socioeconomic measures of disadvantage rather than assuming that identity” is the crucial factor. As an example of such a system, she points to the fact many universities around the world that now use socioeconomic status (SES) measures such as family income, rather than race, to determine entrance qualifications for disadvantaged students. Such “class-based” or “race-neutral” standards have a successful track record in Israel.

SES factors are also widely used in the U.S., although they remain a work in progress. The reason many American schools rely on SES is that they’ve been forbidden from accepting students based solely on race due to court rulings on constitutional grounds. In many cases, however, the universities manipulate their allegedly colour-blind SES rankings in order to sort students by colour regardless of what the courts say. This has led to numerous lawsuits objecting to such subterfuge, including one well-publicized case involving Asian students denied entrance to Harvard University because of their race. (They lost in 2019, but the case is now heading to the Supreme Court.) Regrettably, even plans meant to ignore race somehow end up becoming fixated on race.

The final word on ending to racial employment laws should go to the great human rights advocate Martin Luther King, Jr. King strongly opposed race-based quotas and other affirmative action measures because he anticipated their divisive effect on social harmony. In 1964 he wrote, “It is my opinion that many white workers whose economic condition is not too far removed from the economic condition of his black brother, will find it difficult to accept…special consideration to the Negro in the context of unemployment, joblessness etc. and does not take into sufficient account their [own] plight.” He argued against different treatment based on race because he thought help should be provided to all who need it, regardless of their skin colour. In other words, he dreamt of a truly just and fair world. We’re still waiting.

Source: It’s Time to Abolish the Absurd (and Slightly Racist) Concept of “Visible Minorities”