Of note. One of the reasons that one of the former Chief Electoral Officer did not oppose expatriate voting was his expectation that most will not bother to vote which the 2019 election confirmed although that will likely increase slowly. And yes, riding breakdowns would be useful, but it is interesting to note the Conservative focus on Canadian expatriates in Hong Kong rather than the much larger living in the USA:

Expat voting tripled between the last two Canadian federal elections, and sources who recently spoke with The Hill Times say they expect numbers of those who cast ballots from abroad to continue to trend upwards, opening new opportunities for political parties.

But while a conservative group launched in January is working to boost registration of international electors, there’s no sign of a liberal equivalent.

“I think we’re the only Canadian kind of political-oriented expat group that’s trying to help Canadians get registered [to vote] abroad,” said Brett Stephenson, vice-chair and policy chair of Canadian Conservatives Abroad(CCA), which officially launched in January of this year with an aim, in part, to encourage registration of international voters, in a recent phone interview with The Hill Times from Hong Kong.

Involved in the group are a number of notable names: former Conservative foreign affairs minister John Baird, who now works for a number of international firms in Toronto; Nigel Wright, a former chief of staff to then-prime minister Stephen Harper who’s working for Onex in London, U.K.; Herman Cheung, a former manager of new media and marketing in the Harper PMO who now works for Philip Morris International in Hong Kong; Barrett Bingley, a former adviser to then-foreign affairs minister David Emerson who’s now working for The Economist Group in Hong Kong; Patrick Muttart, a former deputy chief of staff to PM Harper who’s now working for Philip Morris International in London, U.K.; Jamie Tronnes, a former Conservative staffer on the Hill who’s now working as a consultant in Oakland, Calif.; Georganne Burke, an experienced Conservative campaigner and organizer who’s based in Ottawa; and Ian Vaculik, who briefly worked as an adviser in the Harper PMO and now works for KBR Inc. in London, U.K. Mr. Stephenson is also a former Conservative staffer, including to Lisa Raitt during her time as natural resources minister.

“I don’t think the … small ‘L’ liberals have come together to form an organization. I thought they would after we had formed in January, but there still hasn’t been any effort as far as I can see,” said Mr. Stephenson.

Similar efforts have been underway by political parties in the U.S., the U.K., and Australia for decades, said Mr. Stephenson—for example, Democrats Abroad or Republicans Overseas—but similar outreach to Canadian expats has long been a “missing component.”

“We’re about 40 years behind our fellow English-speaking countries when it comes to having some sort of international space to engage with expats abroad,” he said.

Citizens who had resided outside of Canada were barred from voting if they’d lived outside the country for more than five years in 1993, though it was seen as loosely enforced until 2011. In that year’s election, two Canadians who’d been outside the country for more than five years—Gillian Frank and Jamie Duong—had their ballots rejected, a decision they took to court, leading to a January 2019 Supreme Court decision that ruled expats have the right to vote in federal elections no matter how long they’ve lived outside the country. That decision came on the heels of a Trudeau Liberal bill, the Elections Modernization Act, which received royal assent in December 2018 and, among other things, amended the Canada Elections Act to scrap the requirement that only Canadians living outside the country for less than five consecutive years, and who intended to return in the future, could vote.

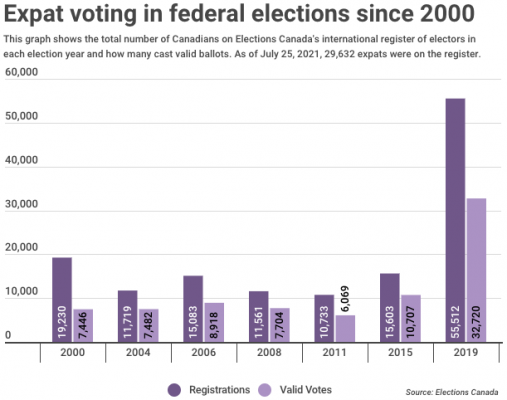

Subsequently, expat voting surged. In 2015, 15,603 expats were registered with Elections Canada as of that year’s election, with 10,707 valid ballots cast. In 2019, 55,512 Canadians were on the international register of electors come the October election, of which 32,720 cast valid ballots, an increase of nearly 206 per cent from the election prior.

Even with the increase, that’s still a small fraction of the total number of Canadians living abroad. The Canadian Expat Association estimates some 2.8 million Canadians live outside the country (the number of eligible voters among that count though is unknown); registration with Global Affairs Canada is entirely voluntary, and only 352,245 Canadians are currently registered.

Graph courtesy of Infogram.

There are early signs that the number of expats registering to vote continues to rise.

On Sept. 13, 2019, two days after the writs were issued and roughly one month out from voting day (Oct. 21) in the last election, the Huffington Post reported that, at that point, 19,784 people were on the international register of electors. That number rose 180.6 per cent to 55,512 by election day.

As of July 25, there were 29,632 Canadians on Elections Canada’s international register of electors—roughly 10,000 more than were on the list one month out from the last election. (Elections Canada does a verification process after each federal election, asking those registered to confirm their continued registration and mailing address, and removes the names of those who don’t respond or have returned to Canada.)

Though it’s still not official that a federal election will happen soon, expectation seems widespread that an election call is imminent, with the vote seen as likely to be held this fall, possibly in September.

“The opportunity is there for expats to have an impact,” said Mr. Stephenson, adding he expects the number of ballots cast by expat voters in the next election to be on par with 2019 levels or to potentially go up. “I don’t think it will dip down.”

John Delacourt, a former Liberal staffer and now a vice-president with Hill and Knowlton Strategies, said the numbers “certainly suggest” expat voting is on the rise.

“If that is indeed the case … it would be viewed as an opportunity, and as an opportunity for outreach, and virtually every party, I think, is interested in growth to connect with members, whether they be beyond our borders” or in Canada, he said.

Semra Sevi, a PhD candidate with the University of Montreal’s department of political science who has explored the subject of expat voting (her master’s thesis looked at the impact of such voters in Canada), said the fact that expat voting appears to be on the rise is “not very surprising,” given increased attention on the matter, and she expects it “will continue to climb,” as political groups increasingly turn their sights to such voters and awareness builds.

Mr. Delacourt said he doesn’t know of a Liberal-equivalent group to the CCA, adding the Conservative effort is “a little ironic” given the party’s past position supporting previous expat voting limits.

The Hill Times asked the federal Liberal Party directly about the existence of any such groups, and none were noted in response, though senior director of communications Braeden Caley did highlight that the party “works both with volunteers and organizers on a series of initiatives to help encourage Canadians abroad to participate in our democracy and elections,” noting “particularly strong support from Canadian students who have been living abroad in recent years.”

Mr. Stephenson and Mr. Bingley previously formed a Canadian Conservatives in Hong Kong group in 2019, on the heels of the Supreme Court’s decision, similarly aimed at encouraging expats to register to vote. Through one registration drive event held a few days before writs dropped in 2019, attended by Mr. Baird, he said the group helped get between 150 to 200 expats registered. (The total number registered overall as a result of the group’s efforts is unknown, as expats have to register themselves.)

“That’s the kind of thing we’re hoping to replicate more on a global level” now, he said, with a particular focus currently on the Asia-Pacific region (Hong Kong, Singapore, and Australia in particular), the European Union (France and Germany in particular), Israel, the U.K., and the U.S., with the latter two being “likely where most Canadian expats live.”

A lot of the group’s work, said Mr. Stephenson, is about “information sharing” and helping expats understand the process of registering, a process that involves “a lot of clicking” and is “not very simplified.” For example, a question that often comes up among expats, he said, is how voting in Canada could impact their taxes (zero impact, he said, citing Canadian tax experts).

Along with expat registration, Mr. Stephenson said the CCA is working to build a conservative network across the globe and has plans to start advertising on social media “soon.” The group also has a third function: providing informal policy advice and feedback to the Conservative Party and caucus back home (as well as provincial conservative parties, “as it comes”—for example, they recently had an open forum discussion with Alberta Premier Jason Kenney, he said).

“Tapping into that network of experience and breadth of knowledge across sectors and countries can help to really inform policy issues back into Canada,” he said. “Canada sometimes gets a little bit isolated in international conversations … and sometimes we don’t read the newspapers in other countries about what’s going on, so we wanted to be able to have that policy feedback loop to improve the discussion back in Parliament a bit more.”

To be on the international register of electors, you need to be a Canadian citizen, at least 18 years old on polling day, and have lived in the country at some point in your life. Elections Canada requires a copy of one piece of ID, either from a Canadian passport, birth certificate, or citizenship card/certificate. Expats also need to provide the last address they lived at in Canada (it can’t be a PO box). That address is used to determine the federal riding in which their vote will be counted. Registration can happen at any time, according to Elections Canada, but must happen before 6 p.m. on the Tuesday before election day (which is always a Monday) to have their vote counted in that election.

Elections Canada begins the process of mailing out special ballot kits to those on the register “immediately after the drop of writs” and it typically takes two to three days to mail all of them out, said spokesperson Matthew McKenna.

“This time around, we have done what we can to prepare kits in advance so we are ready to go as soon as possible,” he said.

How long it takes to reach international voters varies by country, he said, noting the agency uses DHL, a private courier service, for “many destinations.” Completed kits have to be received at Elections Canada’s Ottawa distribution centre by no later than 6 p.m. on election day.

Since 2015, Elections Canada has run a “paid advertising component” to reach out to international electors online; prior to then, it did “some smaller-scale targeted advertising” along with “non-paid outreach and organic communication,” explained Mr. McKenna. The agency also works with Global Affairs Canada to share information with Canadians living abroad about how to register and vote, and has a dedicated section on its website.

Impact of expat voters hard to gauge, says Sevi

In the 2019 federal election, 18.4 million Canadians cast valid ballots. International voters accounted for a small fraction of that, rounded to just 0.2 per cent.

But Mr. Stephenson said he thinks there’s still potential for expats to make an impact. In his understanding, “many of the Hong Kong Canadians,” for example, are from B.C.’s Lower Mainland, the Greater Toronto Area, and Calgary and Edmonton. If “even just 10 or 20 per cent” of Canadians in Hong Kong vote, he suggested “it could tip the scales in a lot of close election races in the GTA and Lower Mainland.” Both areas are seat-rich and seen as target regions by Canada’s major political parties.

Gauging the impact expat voters have had in federal elections is hard to do, said Ms. Sevi. The riding-by-riding vote breakdown currently provided by Elections Canada lumps together all votes by special ballot as one category; that includes international electors, but also captures votes cast by prisoners, members of the military, and people voting domestically by mail-in ballot. (Elections Canada is anticipating mail-in ballot use to rise considerably in the next federal election as a result of COVID-19.)

“It’s hard to disentangle the patterns to say that you know expat votes would make a difference in a specific constituency historically,” said Ms. Sevi. The Conservative Party has in recent elections gotten more votes by special ballot than any other party, she said, but that’s special ballots as a combined group. A Maclean’s piece penned by Ms. Sevi and Peter H. Russell in 2015, notes that in 2008 and 2011, Ontario saw the highest share of expat voters, followed by Quebec, then B.C., then Alberta, with expat votes spread “increasingly in urban ridings.”

However, separate research she’s done into voting by Turkish expats (in Turkey’s elections)—information on which is “disentangled” as a separate category—indicates that while turnout is lower than among domestic voters in Turkey, expats “tend to vote along similar lines as domestic voters.”

Ms. Sevi said she hopes Elections Canada provides a riding-by-riding breakdown of the types of special ballot votes in the future.