‘Words are no longer enough’: Muslim group releases 60 calls to action ahead of National Summit on Islamophobia

2021/07/20 Leave a comment

Of note. Summits are often short-term political events to respond to community and raise broader awareness, providing platforms for organizations and political leaders. More substantive approaches involve more time and preparation than a one-day summit on the eve of an election, which runs the risk of being more virtue signalling than substantive.

And the risk of separate summits for Islamophobia and antisemitism is that the focus on the particular communities distracts from the fundamental commonalities of all groups that experience prejudice, bias and discrimination:

The National Council of Canadian Muslims (NCCM) has released a list of policy recommendations for federal, provincial and municipal governments in Canada to tackle violent and systemic forms of Islamophobia.

Among the 60 policy recommendations are calls for the federal government to create an anti-Islamophobia strategy by the end of the year, for provincial Ministries of Education to develop localized strategies to address anti-Muslim sentiment, and for municipalities to invest in alternative forms of policing to combat increasing harassment and violence against Muslims.

The NCCM is also calling on governments to expand legislation to dismantle white supremacist groups in Canada, to challenge Bill 21 in Quebec, and to provide resources to empower Muslim Canadians to tell their own stories.

The 60 calls to action will be presented at the National Summit on Islamophobia, which will be hosted by the federal government on July 22. A National Summit on anti-Semitism will be held on July 21.

“These summits will bring together a diverse group of community and political leaders, academics, activists, and members with intersectional identities within these communities,” according to a statement by Bardish Chagger, minister of diversity, inclusion and youth of Canada.

On its website, the NCCM says it is an independent and non-partisan organization “that protects Canadian human rights and civil liberties, challenges discrimination and Islamophobia, builds mutual understanding, and advocates for the public concerns of Canadian Muslims.”

For Mustafa Farooq, the CEO of NCCM, the only way to measure the success for the upcoming summit will be whether action is taken or commitments are made in regards to the 60 calls to action and recommendations from other groups. Farooq says the NCCM will release an updated document following the summit to record any commitments made by governments and track any agreed-upon timelines.

“This is not about getting together to talk about best practices,” he told the Star. “This is about committing to action.”

Thursday’s summit comes in the wake of the deadly June attack on a Muslim family in London, Ontario, along with a steep rise in targeted hate crimes against Muslims across the country. According to the NCCM, more Muslims have been killed in targeted hate attacks in Canada than any other G-7 country in the past five years because of Islamophobia. In Alberta alone, at least nine attacks have been reported against Muslim women, most of them Black and wearing a hijab, since December.

On June 11, following calls from the Muslim community and a petition from the NCCM, the House of Commons gave unanimous consent to an NDP motion to convene an emergency summit on Islamophobia. The motion also called on leaders from all levels of government to “urgently change policy to prevent another attack targeting Canadian Muslims.”

Following the motion, the NCCM launched consultations with Canadian Muslims from coast to coast, in search of tangible policy solutions.

“Canada doesn’t have the appropriate infrastructure to challenge Islamophobia,” Farooq told the Star. “There isn’t a single body of governance in this country that is dedicated to fighting Islamophobia. This despite the fact that the impacts of Islamophobia have resulted in the worst attack on a religious institution in modern Canadian history.”

Thus, an overarching theme of the NCCM’s calls to action is the need to institutionalize the fight against anti-Muslim sentiment. This includes the creation of an Office of the Special Envoy on Islamophobia.

“This position needs to work with various ministries to inform policy, programming and financing of efforts that impact Canadian Muslims,” the document reads. “The envoy should have the powers of a commissioner to investigate different issues relating to Islamophobia in Canada, and to conduct third-party reviews across all sectors of the federal government relating to concerns of Islamophobia.”

Another theme found in the NCCM’s recommendations is the need to address the way that education in Canada deals with Islamophobia. Specifically, the organization recommends that provincial education ministries develop anti-Islamophobia strategies that are responsive to local contexts. This includes changes to curricula that relate to Islam, improving religious accommodations for Muslim students and staff, anti-Islamophobia training.

“The reality is that (Quebec City mosque attacker) Alexandre Bissonette and (alleged London attacker) Nathaniel Veltman were young men,” Farooq told the Star. “We need to see a different approach to education, and the way that young people are learning about Canadian Muslims. A large percentage of Canadians have suspicions towards their Canadian Muslim brothers and sisters, and we think education and anti-Islamophobia awareness is a key component.”

NCCM’s document is broader than the 30 calls to action to combat systemic racism and hate that was published by a federal Heritage committee in 2017. However, Farooq believes that now is the time to take bold action.

“Words are no longer enough,” he told the Star. “The reality is that at this point, every single federal political party, the vast majority of the provinces, dozens of municipalities have all expressed their concerns about Islamophobia and Islamophobic violence. Faith communities are united about this, civil society folks are united — Canadians are united about the fact that things need to change. We just need to translate this into real political will to move things forward.”

Here are some of the recommendations from the NCCM’s 60 calls to action.

- The NCCM is calling for the release of a federal anti-Islamophobia strategy by year’s end. The NCCM recommends the strategy include a clear definition of Islamophobia to be adopted across government, plus funding and resources for research, programs and education campaigns to address Islamophobia.

- The NCCM wants the federal government to take action against Quebec’s Bill 21, which bans public servants from wearing religious symbols. Specifically, it wants the attorney general to commit to being an official intervener in court battles on the legislation. The document calls Bill 21 “a fundamentally discriminatory law” that perpetuates the idea “that Islam, Muslims, and open religious expression in general, have no place in Quebec.” The NCCM is also calling for the creation of a fund to financially assist those affected by the legislation.

- Citing the rising tide of online hate and Islamophobia on social media, the NCCM is calling on the federal government to complete a legislative review of the Canadian Human Rights Act, in order to ensure that Canada is equipped to deal with modern forms of Islamophobia and hate.

- The NCCM is calling on the federal government to invest in a national support fund for survivors of hate-motivated incidents or attacks. The NCCM is also recommending changes to the country’s Security Infrastructure Program, to provide funding for security upgrades to mosques and community organizations under threat.

- There are several calls to action dedicated to reforming national security and dismantling white supremacist groups. These include creating legislation “to implement provisions that place any entity that finances, facilitates, or participates in violent white supremacist and/or neo-Nazi activities on a list of violent white supremacist groups, which is separate and distinct from the terror-listing provisions.” The NCCM also calls on provincial governments to introduce legislation that bans white supremacist groups from incorporating.

- The NCCM wants the Criminal Code changed to better deal with what is often called a “hate crime.” Specifically, the group is calling for amendments that “reinvigorate how we approach hate crimes, and that strengthens a prosecutorial approach that lacks consistency, clarity and resourcing across the country,” according to Farooq.

- The document includes several policy changes to tackle systemic Islamophobia at a federal level, including changes to the Canadian Border Services, the Canadian Revenue Agency and Canada’s approach to security and counterterrorism. For example, the NCCM is calling for the establishment of an oversight body specifically for the Canadian Border Services Agency, citing allegations that the agency engages in racial profiling that disproportionately targets Muslims.

- The NCCM is recommending changes to policing at the municipal and provincial levels. This includes investing in alternative forms of policing for municipalities and introducing street harassment bylaws that protect Canadians against hateful verbal assaults. The NCCM also recommends that all provinces adopt the recommendations of Ontario’s 2017 Tulloch report, which calls for a sweeping overhaul in police oversight.

- The document also includes several calls for governments to invest in and collaborate with storytellers, artists and filmmakers to help Muslim Canadians tell their stories and challenge narratives that contribute to all forms of Islamophobia. This includes funding local initiatives to celebrate the long history and contributions of Muslim Canadians.

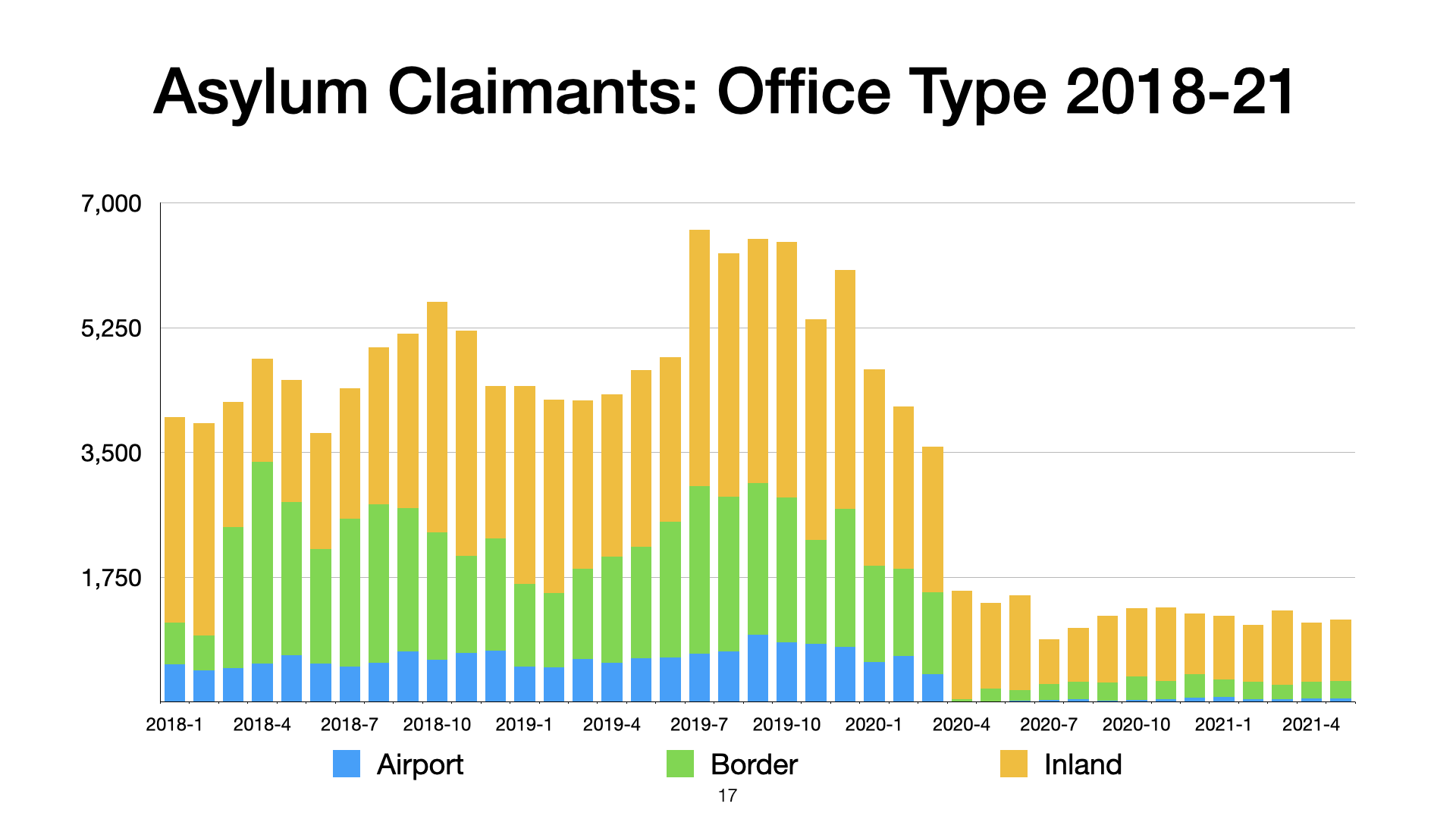

On the good news side, the IRB backlog declined dramatically, with new claims falling by 68% and the backlog by 30%.

On the good news side, the IRB backlog declined dramatically, with new claims falling by 68% and the backlog by 30%.