Black civil servants allege discrimination in proposed class-action lawsuit against Ottawa

2020/12/05 Leave a comment

There is a real disconnect in the proposed class action lawsuit in its broad assertions regarding widespread assertions regarding systemic racism and the reliance on the disturbing personal experiences of 12 Black public servants to justify such broad assertions.

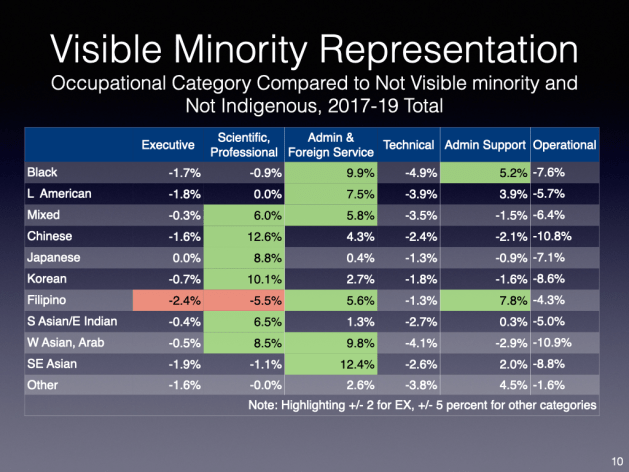

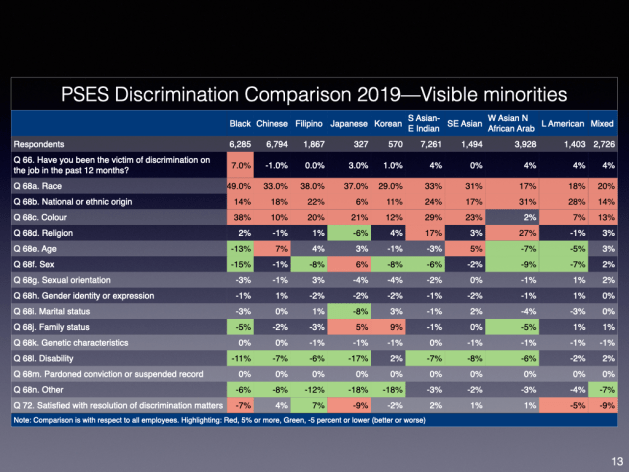

The statement of claim uses no data beyond these personal experiences to justify their claims, surprising given the availability of data from the Census and more recently, TBS employment equity reports and Public Service Employee Surveys as seen in my analyses What new disaggregated data tells us about federal public service … and What the Public Service Employee Survey breakdowns of visible minority and other groups tell us about diversity and inclusion, selected data tables above.

The former shows that overall Blacks are over-represented in the public service but that a number of other minority groups have comparable under-representation to Blacks among executives, i.e., the issues are not unique to Black employees.

On the other hand, Black public servants are more likely to experience discrimination than other groups but even these differences are relatively small.

There are, of course, likely wider variations at the departmental level.

None of this is to discount the experiences of the 12 public servants but underline that calls for systemic change should be evidence-based, not just examples and anecdotes, no matter how strong:

A group of current and former Black civil servants has issued a proposed class-action lawsuit against the federal government alleging it discriminated against Black employees for decades.

They claim the government has excluded Black federal employees from being promoted.

“Our exclusion at the top levels of the public service, in my view, has really disenfranchised Canada from that talent and that ability and the culture that Black workers bring to the table and that different perspective,” said Nicholas Marcus Thompson.

Thompson is one of 12 former or current employees from multiple government departments who are representative plaintiffs in the class action. Lawyers representing them say the suit could ultimately cover tens of thousands of people who have worked in the federal public service since 1970.

The lawsuit comes at a time of heightened awareness about systemic and anti-Black racism.

In June, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said systemic racism “is an issue across the country, in all our institutions.”

The plaintiffs in the proposed class action are asking for $900 million in damages, a declaration from the government that it infringed on the group’s charter rights and a plan going forward to promote more Black employees.

It was filed in the Federal Court of Canada on Thursday and is awaiting certification. The government is expected to be served in the coming days.

Lack of representation

The lawyers representing the civil servants say the suit is likely the first of its kind in Canada involving Black public servants at the federal level. The statement of claim names more than 50 departments and agencies as comprising the public service.

Last year, two Black Ontario government employees sued the Ontario Public Service, among others, alleging discrimination because they were Black women.

In an interview in Toronto with CBC News, Thompson said that when he joined the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) six years ago, something felt off to him.

“When I became a Canadian citizen many years ago, I remember the citizenship judge saying that Canada is a place where freedom abounds and opportunities are endless. But when I joined the CRA, that was my expectation that I could join, start at any position and climb the ranks. And my goal was really to serve Canadians,” he said.

“I quickly realized that the agency was not, you know, as I thought it would be: all inclusive and diverse.”

Thompson, who was a collections officer, said a lack of Black representation in the agency caused his morale and confidence to suffer. He also said the work environment was toxic and led to illness.

When his doctor gave him a prescription for a “workplace accommodation,” Thompson said he was told to clean closets because no other work was available.

The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, which is the employer of the federal public service, said it could not comment on the allegations in the suit because it was before the courts.

“Systemic racism and discrimination is a painful lived reality for Black Canadians, racialized Canadians and Indigenous people,” said spokesperson Bianca Healy in a statement.

“The government has taken steps to address anti-Black racism, systemic discrimination and injustice across the country.”

She said that includes a recently announced $12 million for “a dedicated Centre on Diversity and Inclusion in the Federal Public Service.”

The CRA referred CBC News to the Treasury Board statement.

Complaints in multiple departments and agencies

Bernadeth Betchi is another representative plaintiff who also worked for the CRA off and on for several years.

In a Skype interview, she described a toxic workplace where she said she experienced microaggressions and had to go on sick leave. She had to work twice as hard as her non-Black colleagues to get noticed, she said.

Betchi ended up leaving the CRA and eventually found work at the Canadian Human Rights Commission (CHRC) — a federal organization that handles complaints about discrimination.

“Everything that they are about was everything that I am about, you know, it resonated with my values. It’s there to help Canadians — Canadians who have been discriminated against, you know, on different grounds. And so I knew that this is where I needed to be,” said Betchi, who’s on a maternity leave from the CHRC.

But her views quickly changed.

“When I started working there, I saw that, unfortunately, what the mandate says and what’s being done inside of the organization is completely different. Black folks within the Canadian Human Rights Commission, my Black colleagues, are suffering. They’re being — there’s a lot of adverse differential treatment.”

When asked to comment on the allegations, CHRC said it “is committed to meeting the highest standards of equality, inclusion and representation” and that it has been “examining how racism may manifest itself within our organization and what steps might be needed to address it.”

“We know that Indigenous, Black and other racialized people face many societal, institutional and structural barriers to equality,” said spokesperson Jeff Meldrum in an email.

“That is why work is underway to ensure that the views and perspectives of Indigenous, Black and other racialized employees on barriers that may exist within the Commission are heard and addressed. ”

Proposing solutions

“There is a grave injustice that’s taking place,” said Courtney Betty, a Toronto lawyer involved in the class action.

“I think every Canadian should be troubled.”

Betty and his colleague, Hugh Scher, decided the lawsuit’s time frame would start in 1970, the year Canada ratified the United Nations international convention on the elimination of all forms of racial discrimination.

In a joint interview, Betty and Scher spoke about possible solutions they hope will stem from the lawsuit if it’s certified.

“There needs to be a third-party audit undertaken by an independent body, whether that’s a former Supreme Court justice, whether that’s a Black equity commission,” Scher said.

That third party should do a thorough review “to see what are the barriers to true equality and access and inclusion for Black employees, and what can be done about them,” he said.

Scher said another key element would be amending the federal Employment Equity Act.

Its stated goal is “to achieve equality in the workplace so that no person shall be denied employment opportunities or benefits for reasons unrelated to ability.”

The legislation is also designed “to correct the conditions of disadvantage in employment experienced by women, Aboriginal peoples, persons with disabilities and members of visible minorities.”

But the lawyers argue that because Black employees are grouped together with all non-white and non-Indigenous people as “visible minorities” under the act, they’ve suffered by not moving up in the public service — and the unique racism they have to deal with has been ignored.

Betchi agrees. “There’s not a lot of Black women or Black men at the executive level,” she said. “Our experience has been completely invisible and put aside.”

The Treasury Board has data that breaks down the “visible minority” category in the public service based on self-reporting by employees. It shows that in 2019, Black workers made up a smaller proportion of those in top-level executive positions than those doing administrative support.

Thompson said he’s optimistic the lawsuit will spark change.

“I’m very hopeful that this issue will be addressed in a forthright manner by the government of Canada,” he said. “The government has shown signs that it is prepared. It has done the first major part by acknowledging that this issue exists.”

Source: Black civil servants allege discrimination in proposed class-action lawsuit against Ottawa

Text of proposed class action suit: 486848991-NICHOLAS-MARCUS-THOMPSON-ET-AL-v-HER-MAJESTY-THE-QUEEN

A longer more in-depth account of the experiences of the 12 employees can be found here:

The Canadian government has failed to uphold the Charter rights of Black employees in the federal public service, shirking its responsibility to create discrimination- and harassment-free workplaces, and actively excluding Black bureaucrats, allege plaintiffs in a proposed class-action lawsuit.

“There has been a de facto practice of Black employee exclusion throughout the public service because of the permeation of systemic discrimination through Canada’s institutional structures,” said the statement of claim filed with the Federal Court in Toronto on Dec. 2.

The class action, which has not been certified, is being led by 12 former and current Black public servants, who have been employed in a variety of federal departments and agencies, including the RCMP, Canadian Revenue Agency, Canadian Human Rights Commission, Canadian Armed Forces, Statistics Canada, Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada, and Employment and Social Development Canada.

The representative plaintiffs, seeking $900-million in damages on behalf of public servants since 1970 and their families, claim Black employees have been systemically excluded from advancement within the public service and that the court should impose on the government a mandatory order to implement a “Diversity and Promotional Plan for Black Public Service Employees, related to the hiring and promotion” of Black bureaucrats.

“Canada owes Black employees a duty of care,” the 45-page statement of claim said. “This duty entails an obligation to promote Black employees based on merit, talent, and ability, as is the case for any other employee.”

The suit alleges that Canada’s application of the Employment Equity Act violates the Charter equality rights of Black employees. The act designates women, Indigenous people, persons with disabilities, and visible minorities as requiring special measures and accommodation in the public service.

“In particular, the act fails to break down the category of visible minorities and thus ignores the unique, invisible, and systemic racism faced by Black employees relative to other disadvantaged groups that are covered by the categories established by the act,” the statement of claim said, adding that decisions on hiring and promotions are governed by enabling legislation for the public service, and not subject to union grievance.

By not hiring and promoting Black employees in a manner proportional to their numbers in the public service or the overall population or to a degree consistent with the treatment of other visible minority or white public servants, “Canada has treated Black employees in an adverse differential manner and has drawn distinctions” between Black bureaucrats and those of other races.

Requests for comment from the federal Attorney General’s Office were referred to the Treasury Board Secretariat.

“As this matter is currently before the courts, the Treasury Board Secretariat cannot comment on this suit at this time,” said an email from a department spokesperson.

“The government has taken steps to address anti-Black racism, systemic discrimination, and injustice across the country. Most recently, the fall economic statement committed $12-million over three years towards a dedicated Centre on Diversity and Inclusion in the Federal Public Service. This will accelerate the government’s commitment to achieving a representative and inclusive public service,” the email said, also highlighting the September Throne Speech where the government “announced an action plan to increase representation and leadership development within the public service.”

“Early in its mandate, the government also reflected its commitment in mandate letters, in the establishment of an Anti-Racism Strategy and Secretariat, in the appointment of a minister of diversity and inclusion and youth, and in the creation of the Office for Public Service Accessibility,” said the Treasury Board Secretariat statement.

In February, Treasury Board President Jean-Yves Duclos (Québec, Que.) told The Hill Times that “the fact that Black employees tell us they are unable to be at their full potential is something of great concern to us. I will certainly address those concerns and make sure that every federal employee, including Black employees, has the ability to make the fullest impact on our society.”

NICHOLAS MARCUS THOMPSON ET AL. v. HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN by Charelle Evelyn on Scribd

Plaintiffs outline alleged mistreatment, exclusion

One of the representative plaintiffs, Nicholas Marcus Thompson, a union leader who was named activist of the year in January by the Public Service Alliance of Canada in Toronto, works for the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA). Mr. Thompson has “repeatedly been denied promotions as a consequence of his race and due to his advocacy on behalf of other Black employees,” the statement of claim alleges.

One of the representative plaintiffs, Nicholas Marcus Thompson, says in the statement of claim that ‘merit was not a guiding principle for project assignment or advancement’ of Black public servants.

Mr. Thompson, who ran as an NDP candidate in Don Valley East, Ont., in 2019, said in the statement of claim that Black employees “were ghettoized in the lower ranks” of the public service and that “merit was not a guiding principle for project assignment or advancement.” Prejudice and indifference that “made the world polite, cool, and lonely to the point of permanent exclusion” are “Canadian-style systemic racism,” the claim said.Jennifer Philips has worked for the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) for more than 30 years, during which she has only been promoted once, according to the claim. “She watched as fellow non-Black colleagues, some of whom she had trained, climbed the ranks and enjoyed the benefits of a system designed to lift them up while holding her down.” The claim said she and other Black colleagues were also subject to “explicit and demeaning comments” made about their race, national or ethnic origin, as well as “attitudes and comments dismissing their ability to carry out their duties because of their race and ethnicity.”

Shalane Rooney was one of two Black employees in a roughly 300-person Statistics Canada office. Ms. Rooney began working for the agency in 2010, and in addition to being denied promotions and raises, said, according to the statement of claim, she was subject to comments “regarding [her] hair, [her] skin being too fair to have two Black parents, [colleagues] confirming with [her] if it is okay to say the ‘N’ word,” and more.

Other plaintiffs, such as Yonita Parkes, said that after complaining about race-related treatment by co-workers, the perpetrators were shuffled out laterally instead of being held accountable, while she was ostracized.

Daniel Malcolm highlighted in the statement of claim that Black employees like himself can be overlooked for permanent roles, despite acting in them for some time, because management can set their own criteria to make their preferred appointments from candidate pools, despite qualification or competition score.

Alain Babineau—a 28-year RCMP veteran who served on the protection detail for prime ministers Jean Chrétien, Stephen Harper, and Justin Trudeau (Papineau, Que.) before leaving the force in September 2016—alleges in the statement that his first attempts to join the force in the early 1980s included being asked “What are you going to do if you get called a ‘nigger?’” during his recruiting interview, and later being racially profiled and falsely characterized as a drug dealer. Once he made it into the force, he was referred to as “Black man” instead of his name by the head of the drug section in which he worked. “This is the type of microaggression we endured as Black officers, but we shut our mouths and endure, on the belief that we can help to bring about change,” he said in the statement.

Bernadeth Betchi, who at one point was employed by the Prime Minister’s Office as a communications assistant to Sophie Grégoire Trudeau, alleges in the statement that her employment at both the CRA and the Canadian Human Rights Commission ultimately caused her stress, anxiety, and trauma. “As a consequence of the experiences of mistreatment and Black employee exclusion, [Ms.] Betchi lost faith in the commission’s ability to execute its mandate, seeing as it could not even promote equity within its own teams.”

Liberal MP Greg Fergus chairs the Parliamentary Black Caucus, which highlighted ‘systemic discrimination and unconscious bias’ in the federal public service in its June 16 statement and recommendations.

Repeated calls for change

The hiring, promotion, and overall treatment of people of colour within the public service, specifically Black people, has been a long-standing issue.

A 2000 report by the Treasury Board-created Task Force on the Participation of Visible Minorities in the Public Service noted that the federal public service, “which can be inhospitable to outsiders, can be particularly so to visible minorities,” and recommended, among other things, that the government set a benchmark for one-in-five “for visible minority participation government-wide” within the next five years.

The most recent report on employment equity in the core public service, covering the 2018-19 fiscal year, said that of the 203,286 employees tallied in March 2019, 54.48 per cent were women (compared to an estimated workforce availability of 52.7 per cent), 5.1 per cent were Indigenous persons (against an estimated workforce availability of four per cent), 5.2 per cent were people with disabilities (compared to nine per cent workforce availability), and 16.7 per cent were visible minorities (compared to 15.3 per cent). According to the report, 19 per cent of those who identify as a visible minority in the public service are Black.

Since its establishment in late 2017, the Federal Black Employee Caucus has been pushing to get disaggregated employment equity data collected so that employees, employers, and policy-makers can all understand the landscape for Black federal bureaucrats, and to provide an element of support and unity for Black employees who are facing harassment and discrimination in the workplace.

Former senator Donald Oliver has long championed the idea of a new federal government Department of Diversity headed by a Black deputy minister, and former Liberal-turned-Independent MP Celina Caesar-Chavannes introduced a private member’s bill in the dying days of the last Parliament to change the Employment Equity Act. The bill called for a requirement of the Canada Human Rights Commission to provide an annual report to the minister “on the progress made by the Government of Canada in dismantling systemic barriers that prevent members of visible minorities from being promoted within the federal public service and in remedying the disadvantages caused by those barriers.”

There are so few people of colour at the deputy and associate deputy minister level that the government won’t release numbers, for privacy reasons. Caroline Xavier, became the first Black woman to work at that level of the public service when she was appointed associate deputy minister of Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada in February.

In October, the government awarded a contract worth $164,415 to executive recruitment firm Odgers Berndtson to “establish and maintain on an ongoing basis an inventory of qualified and interested Black people and other racialized groups, Indigenous people, as well as persons with disabilities, from outside the federal public service for the Government of Canada to consider for the deputy minister and assistant deputy minister cadre.”

In its June 16 statement, the Parliamentary Black Caucus also highlighted “systemic discrimination and unconscious bias” in the federal public service. Signatories called for measures that included improving Black representation in the senior ranks of the public service, implementing anti-bias training and evaluation programs, and establishing an “independent champion for Black federal employees through the creation of a national public service institute.”

Source: ‘Canadian-style systemic racism’: Black public servants file suit against federal government