The latest. Some encouraging trends:

Immigrants admitted to Canada in 2016 reported a median entry wage of $25,900 in 2017, the highest recorded among immigrants admitted since 1981. Although the entry wages of recent immigrants have increased over the past few years, their income remains lower than that of the overall Canadian population. The Canadian Income Survey estimated the Canadian population’s median wage at $36,100 in 2017.

When immigrants arrive in Canada, they face a number of challenges, such as getting their credentials recognized, being able to speak one of the official languages and acquiring Canadian work experience. However, the longer immigrants live in Canada, the more their income increases and, for some, their income reaches the level of the overall Canadian population.

This analysis uses new data from the Longitudinal Immigration Database (IMDB), which comprises information on permanent and non-permanent (temporary) residents, including asylum claimants. It presents the type of information that can be extracted from the IMDB and its outputs to better understand how the socioeconomic situation of these individuals has evolved.

Recent immigrants have higher entry wages and more work experience prior to admission than before

Over the past 10 years, the median entry wage of immigrants, one year after admission, in 2017 constant dollars, has increased from $20,400 for the 2007 admission year to $25,900 for the 2016 admission year (+27%).

Not all immigrants face the same challenges after admission. Those who had work experience in Canada upon admission reported the highest median entry wages. For the 2016 admission year, income one year after arrival was $39,800 for study and work permit holders, and $38,100 for work permit holders only. These wages are comparable with those of the entire Canadian population. For immigrants who had no experience prior to admission, or who had a study permit only, incomes were $19,900 and $12,500, respectively.

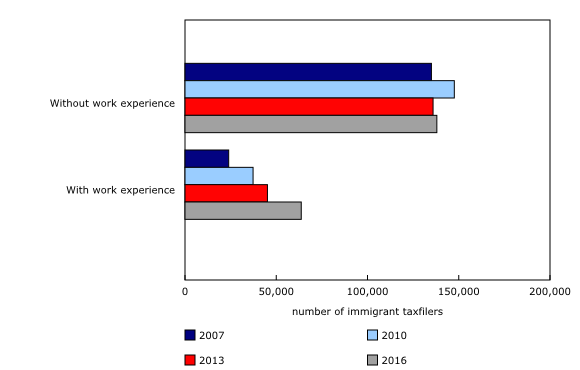

In recent years, an increasing number of non-permanent resident permit holders are transitioning to permanent residence. The observed growth in entry wages can be partly accounted for by differences in income between immigrants with pre-admission work experience in Canada and immigrants without such work experience. From the 2007 admission year to the 2016 admission year, the number of immigrant taxfilers one year after arrival who had work experience in Canada increased by 166%, while the number of immigrants without work experience rose 2%.

Chart 1

Number of immigrant taxfilers one year after admission, by admission year and work experience in Canada prior to admission

Immigrants who hold at least a pre-admission study permit have stronger wage catch-up in the 10 years after admission

Overall, immigrants’ wages increase with the number of years since admission and, for some, their wages eventually reach that of the overall Canadian population ($36,100). For example, the median wage for immigrants admitted in 2007 increased from $20,400 in 2008 to $33,500 in 2017, an increase of 64%.

Wage catch-up factors include pre-admission work experience, which facilitates integration through increased knowledge of official languages and the development of professional networks in Canada, among other things. In 2017, immigrants admitted in 2007 who had held both a study permit and a work permit prior to admission had the highest median wage (up 81% to $63,800), and their wage exceeded that of immigrants who held only a work permit (up 36% to $48,100) and that of Canadians as a whole. The median wage of immigrants admitted in 2007 who held only a pre-admission study permit increased significantly over 10 years (up 163% to $37,600) and now exceeds the median wage of immigrants without pre-admission experience (up 72% to $30,700).

Chart 2

Median wage of immigrants admitted in 2007, 1 year and 10 years after admission, by pre-admission experience

The median wage for asylum claimants increases with length of residence in country

Asylum claimants are individuals who request refugee protection in Canada. Because of their situation, they face many challenges in terms of economic integration. Even after their refugee claim is accepted, asylum claimants have lower median wages than other immigrants with pre-admission experience.

According to a Statistics Canada article on asylum claimants published earlier this year, the number of claimants fluctuated from 2000 to 2018 and reached over 50,000 in 2017 and 2018. Asylum claimants are relatively young. Of those who arrived in 2017, 39% were younger than 25 years of age, while 14% were aged 45 or older.

The median entry wage for asylum claimant taxfilers refers to their income one year after they submitted their refugee claim. Among those who claimed refugee status from 2006 to 2016, the median wage fluctuated between $10,900 and $16,000. As with immigrants, the median wage of asylum claimants increases with each additional year spent in the country. Therefore, the median wage for those who submitted a refugee claim in 2006 was $14,100 in 2007 and $28,600 in 2017.

There are significant differences in income among the top 15 countries of origin for asylum claimants. Among asylum claimants in 2012 who filed taxes in 2017, the highest median wages were reported by claimants from Sri Lanka ($31,600), Somalia ($30,700) and Nigeria ($30,700). Claimants from Afghanistan ($18,200), Iraq ($17,300) and China ($14,300) reported the lowest median wages.

Economic immigrants and their dependants stay more frequently in their province of admission when they have pre-admission work experience

Reasons for immigrating to Canada can influence the likelihood of immigrants to remain in their province of admission over time. For example, family class immigrants come to Canada to be closer to their loved ones, while economic immigrants are selected based on their ability to contribute to the Canadian economy.

In 2017, 86% of immigrant taxfilers admitted in 2012 filed a tax return in their province of admission. The provincial retention rate was highest among family-sponsored immigrants (93%) and slightly lower among refugees (87%). For economic immigrants and their dependants, the retention rate was 82%. However, for these immigrants, the rate was higher among those with a pre-admission work permit only (90%) than among those with no pre-admission experience (81%).

Opening the Government of Canada documents the digital responsiveness of the federal bureaucracy in the later stages of Stephen Harper’s Conservative government. Clarke consults an abundance of what academics call grey literature, namely media coverage, government tweets and blogs, and completed access to information requests. She gains original insights through interviews with 32 Canadian public servants and a special adviser. Those are buttressed by conversations with seven public servants in the United Kingdom. They narrate a consistent theme: that the Canadian government is cautious and hesitant about digital reform.

Opening the Government of Canada documents the digital responsiveness of the federal bureaucracy in the later stages of Stephen Harper’s Conservative government. Clarke consults an abundance of what academics call grey literature, namely media coverage, government tweets and blogs, and completed access to information requests. She gains original insights through interviews with 32 Canadian public servants and a special adviser. Those are buttressed by conversations with seven public servants in the United Kingdom. They narrate a consistent theme: that the Canadian government is cautious and hesitant about digital reform.