Dave Snow: As the U.S. abandons DEI, Canada doubles down

2025/02/05 Leave a comment

On some of the excesses. Likely that a future conservative government would eliminate granting council requirements among other programs:

While the U.S. government, corporations, and universities begin to abandon Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) policies, Canada has instead doubled down, continuing to make them an integral part of both government and academia.

This trend has become increasingly apparent in federal granting agencies, the main source of Canada’s research funding, whose combined budget is nearly $4 billion.

In my new Macdonald-Laurier Institute report—“Promoting Excellence—Or Activism? Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion at Canada’s Federal Granting Agencies”—I find DEI has now become fully infused into all three of Canada’s granting agencies: the National Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC).1

Their DEI initiatives range from specialized race, gender, and diversity grants to revised definitions of “research excellence” to mandatory bias training for most peer reviewers. As a result, a growing proportion of grants are awarded to projects with explicitly activist subject matter. All this adds to the idea that Canada’s research funding process has become politicized, further undermining the public’s faith in universities.

The colours of the DEI rainbow

My report identifies three categories of DEI (or “EDI,” as typically fashioned by the federal government) at Canada’s granting agencies.

Mild DEI uses the language of DEI in vague, unobjectionable terms to push for greater institutional diversity.

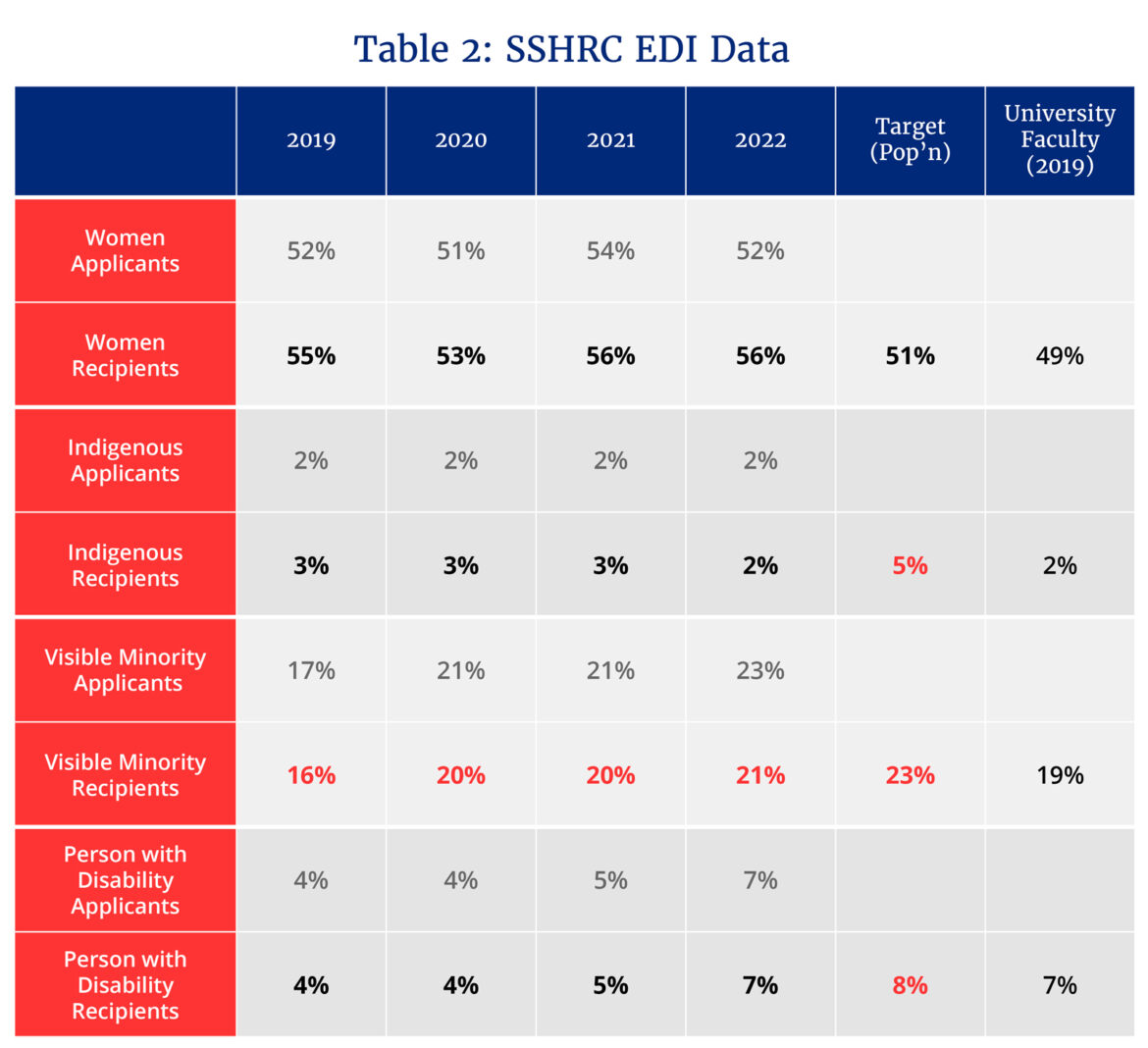

Moderate DEI uses DEI as a substitute for affirmative action. Under the guise of “equity targets” or “equalization” of grants through preferential awarding processes, Moderate DEI seeks to increase the number of awards given to those who identify as Indigenous, women, visible minorities, LGBTQ+, and persons with disabilities.

Finally, Activist DEI uses the language of DEI to advance the goals of critical social justice activism. This category is broadly consistent with what many call “wokeness.” Activist DEI views society, in the words of University of Buckingham professor of politics Eric Kaufmann, “as structured by power hierarchies of white supremacy, patriarchy, and cis-heteronormativity.” It aims to “overthrow systems of structural racism, sexism, homophobia, and transphobia.” Activist DEI is utterly incompatible with the creation of objective, falsifiable academic research—yet it is increasingly creeping into granting agencies’ guidelines, definitions, and reports. CIHR has even embedded Activist DEI into how it evaluates success, updating its Research Excellence Framework to say, “Research is excellent when it is inclusive, equitable, diverse, anti-racist, anti-ableist, and anti-colonial in approach and impact.”

The ambiguous meaning of DEI enables scholars and institutions to hide behind Mild DEI language while advancing Activist DEI research agendas. Canada’s granting agencies claim that equity merely means the “removal of systemic barriers.” But in practice, SSHRC-administered Canada Research Chair positions often exclude applicants who are white and male.

The agencies claim diversity is only “about the variety of unique dimensions, identities, qualities and characteristics individuals possess.” But SSHRC’s Guide to Including Diversity Considerations includes eleven sources about intersectionality.

The agencies insist that inclusion merely ensures “all individuals are valued and respected for their contributions and are supported equitably in a culturally safe environment.” Meanwhile, CIHR funds and promotes a workshop whose participants envision a day where “Public health is no longer run by nauseating Whiteness [sic].”

The result is a confusing mélange of DEI terminology that inevitably nudges students and scholars towards activism in their grant and scholarship applications. Unsurprisingly, many prestigious grants are ultimately awarded to Activist DEI projects. Building directly off preliminary research I completed for The Hub, my new report assessed more than 2,600 individual SSHRC awards between 2022 and 2024. As expected, Activist DEI language was present in as many as 63 percent of project titles for the federal government’s specialized identity-focused “Future Challenge” grants.

More troublingly, Activist DEI language was present in many of the titles of SSHRC’s prestigious Insight Grants (10 percent) and Insight Development Grants (14 percent). These grants are supposed to promote research excellence; instead, they are funding projects with titles such as “Just Kids: Children and White Supremacy” and “Reclaiming the Outdoors: Structures of Resistance to Historical Marginalization in Outdoor Culture,” with the latter costing taxpayers more than $250,000.

Seeking solutions

What can be done to fix this? My report makes several recommendations for reform. Amend the granting agencies’ legislation to enshrine a commitment to political and ideological neutrality. Remove all references to DEI from agency guidelines. Eliminate DEI-themed grants. End the practice of “equity targets” and preferential awards.

But also, avoid the instinct to “ban” DEI-driven research from award consideration. Such bans are antithetical to academic freedom. Instead, let Activist DEI scholars make the case that their research deserves scarce taxpayer resources—resources that will be awarded on objectively meritorious criteria related to research excellence and knowledge production, rather than adherence to fashionable political activism.

Canadian universities are in need of substantial reform, and removing DEI considerations from federal granting agencies will not be a catch-all fix to the problems of ideological diversity, intolerance, and bloated bureaucracies that plague our higher education. But it would be a good start. The granting agencies remain committed (in principle) to research excellence and objective knowledge creation, which is more than can be said of much of the Canadian academy. They continue to fund indispensable research in health, hard sciences, and social sciences. Thankfully, the proportion of prestigious grants given to Activist DEI research remains small. But, while a DEI fixation has not yet caused irreparable harm to the agencies, it runs the risk of permanently damaging their reputations.

The first step in fixing higher education in Canada should come from the top. It is time for the federal government to depoliticize grant agency funding and remove DEI from the agencies’ domain.

Source: Dave Snow: As the U.S. abandons DEI, Canada doubles down