Good long read on how the impact of COVID-19 will likely increase inequality further:

Two weeks before vice-principal Brandon Zoras was to welcome a group of students back to the classrooms at Toronto’s Westview Centennial Secondary School, a message appeared in his LinkedIn inbox from a stranger.

“Hi Brandon, hope you are doing well! I am looking for an experienced TDSB Grade 11 chemistry tutor to coach my son online only (due to social distancing) – to start right away. Please let me know if that is something you (or someone you know) can help my son with. Best regards.”

Irritated, Mr. Zoras groaned and deleted it without replying.

Westview has one of the largest Black student populations in the country and sits in the northwest corridor of Toronto, which has become the epicentre for COVID-19 infections. Many students live in cramped housing, have parents who are essential workers and rely on public transit to get around, all things that contribute to the high infection rate – which is 10 times that of the least-infected parts of the city. The average annual income for residents in the area is $27,984 – half of what it is for Toronto as a whole.

“It makes my heart hurt for the families who can’t afford a tutor or who can’t afford all these additional things,” said Mr. Zoras, a science educator.

Since he began working as an educator 11 years ago, he has seen the way public education funding has been diminished, how families in the system have found ways to privatize parts of their children’s schooling to get what they want. Education advocates say those efforts are making things less equitable for everyone else.

Every year, parents across the country lobby to get their children into advanced-placement classes, buy houses in neighbourhoods that will give them access to coveted schools and fundraise on the school council to bring in technology and high-level arts programming.

Now, with the return to school amidst a global pandemic, those efforts to secure the best for their children, known in sociology as “opportunity hoarding,” have become more overt. The confidence many had in the public-education system has been ripped apart because of reopening plans and it seems no amount of fundraising, private meetings with principals or school council strategizing can bring about the changes many are seeking for a safe return to school.

The result is some of the most privileged public-school families are opting for distance education, hiring personal tutors and forming private learning pods – decisions that are ostensibly made in the best interests of their children, but which will likely cause major rifts across race and class. Those in lower-income communities are also choosing remote learning because they have elderly relatives living with them who are vulnerable to getting sick, they feel a heightened threat from COVID-19 because they are in areas with the highest infection rates and the buildings in which they live pose challenges to getting to school on time in a pandemic.

That families on both ends of the socio-economic spectrum are opting for remote learning exposes cracks that already existed in the system. There’s a threat the most privileged will pull out to customize their own education since they can afford to, while others who are fearful of sending their children back to school but cannot pay for private help are becoming test subjects for a new realm of online learning. As plans are pulled together haphazardly, there’s a concern the divide will deepen.

This week, school boards in Toronto, Peel Region and Halton Region released the results of parent surveys that show a sizable portion of students will not be in classes this fall: 30 per cent of elementary and 22 per cent of high school students for Toronto; 33 per cent combined for Peel; and 29 per cent elementary and 15 per cent high school for Halton. A portion of households didn’t respond and school staff will be reaching out to them directly, which could change these figures.

At Thorncliffe Park Public School, in a community that has long been a landing pad for newcomers and where the median household income is $46,595, 38 per cent of families surveyed say they’ll do remote learning this fall.

Munira Khilji, a mother of two in Thorncliffe Park, said many parents she knows chose this option because they live in high-rises and don’t want to endure waits of an hour or longer just to take the elevator while pandemic-related capacity limits are in place – and they worry about physical distancing in such a cramped space.

The issue is most apparent in Ontario, where families have been given a clear choice between in-person and remote learning, but it’s forcing a reckoning in many other parts of the country. In Alberta, 28 per cent of students in Edmonton’s public school board have chosen remote learning. In British Columbia, Education Minister Rob Fleming has said that school districts have the flexibility to provide remote learning options, but there is confusion among parents and school officials as to what that will mean and whether students will remain enrolled in their home schools.

“What COVID has done once again is expose the stark inequities in our system and the realities that families in marginalized communities have to navigate,” said Jeewan Chanicka, the former superintendent of equity, anti-racism and anti-oppression at the Toronto District School Board. “These families also know that their communities are going to be hit the hardest. They are behaving in a way where they’re trying to save their children’s lives.”

Some worry the shift out of the classroom could have devastating long-term consequences: If parents come to appreciate the increased attention their child gets from a teacher in a pod with just four other students, they might opt to continue this post-pandemic and permanently withdraw from a system whose funding is determined by head count.

“Where I worry a bit is in particular for those of privilege; if they’re pulling their children out, whether or not they will return to public education, I don’t know,” Mr. Chanicka said. “My hope is that yes, this is a blip because of the pandemic.”

COVID-19 has presented an opportunity to rethink how Canada operates homeless shelters and long-term care – will the same be true for schools, or will navigating the pandemic only further fracture the system?

Before Marty Menard even had a daughter, he and his wife had done their homework on which school they wanted her to attend. Wortley Road Public School in London, Ont., a well-regarded K-8 school known for its small student population and very involved parent community, stood out. When Mr. Menard’s wife was in her third trimester, they bought a house in Wortley Village, which the Canadian Institute of Planners dubbed the best neighbourhood in Canada in 2013, so they’d be in the catchment area for the school they determined was their first and only choice.

In his daughter’s second year there, Mr. Menard enthusiastically joined many of the various parent committees and even became co-chair of the school council, helping organize fundraisers, the breakfast program and cultural celebrations.

When schools shut down in mid-March, Mr. Menard turned to a private tutoring program to offer his daughter an hour of instruction a day and also found a few hours each week to use online resources from the Khan Academy to help boost her development. But after a few months, his daughter said she was lonely and Mr. Menard knew this couldn’t continue into September. A learning pod seemed like the best solution: The risk of his daughter being exposed to the novel coronavirus would be lower than it might be in a packed classroom, but she would still enjoy social interaction. On social media, he found a few other parents and a provincially certified teacher who will lead the pod, but is struggling to find a space that will host them without greatly increasing the costs, which he estimates will be about $500 to $750 a month.

With school already under way in some provinces and just a few weeks away in others, the scramble to clear those logistical hurdles has sent plenty of parents who have chosen the same option as Mr. Menard into a frenzy.

As August wore on, the panic among parents in the Learning Pods – Canada Facebook group was palpable. Thousands from Vancouver Island to Halifax, but mostly in Ontario, had flocked to the group to find others in their neighbourhood to pod up with, to find a teacher to hire, or to share their story about turning to this option to protect an immunocompromised member of their family.

They solicited advice on everything from costs (“Can folks share how much is a reasonable salary to offer a teacher for a pod of four?” asked one mom in Hamilton) to insurance (“My insurance company approved extended insurance for each child in my pod. They will not cover communicable disease transmission. Has anyone else figured out how to get around this? Co-op among parents to share the responsibility? Corporation to reduce risk?” wrote another in Waterloo, Ont.). Some pods will rotate between a group of households where parents share teaching duties; others will be situated in rented spaces with lots of technology and resources provided and come with a cost of up to a few thousand dollars a month.

On and offline, the conversation on learning pods often leads to bigger questions of equity: are they classist? Do they further the divide between the haves and the have nots? Shouldn’t parents with enough privilege to put their children in a learning pod harness it to lobby the government to make classrooms safe for all children?

Those debates have arisen in Mr. Menard’s own marriage. He describes himself as a “lefty” and a proponent of the public school system, which he says has been steadily defunded for years – but still, he and his wife have decided that given the pandemic and the government’s plans, this is the best option for his family.

“Nothing is going to marginalize kids more than people like me who could afford a learning pod,” he says. “The bottom line as a parent is I still have to put my kid’s interests above every other point of view or political point of view that I have.”

It’s a rationale sociologist Margaret Hagerman encountered again and again when she spent time with affluent white families in the American Midwest as part of research for her book White Kids: Growing Up with Privilege in a Racially Divided America. She observed a phenomenon she dubs “the conundrum of privilege”: Parents who identify as progressives, who care about equity, who may have taken their children to the climate strike or hung up a Black Lives Matter poster in their window, don’t think twice about what it means to give their children advantages that others don’t have access to. They want to raise their children in a just society, but they’ve used their privilege to work against that very goal.

“I think we need to reconfigure what we mean when we say we are doing the best for our child or being the best parent,” she said. “I don’t actually think that advocating for your own kid when that harms other people is the best version of anything.”

When parents talk about the gifts they want to give their children for the future, she likes to challenge them: “Don’t you want your kid to live in a society with less racial violence and with less inequality and social conflict and social problems and suffering?” she asks. “If you could do things now that would provide that different future for your child and the other children around him, it’s kind of philosophical, but I just think that that’s a compelling argument.”

While some who have opted for pods defend their choice with the argument that this will make classrooms less populous and therefore safer for students who do attend in person, the net effect isn’t the reduced class sizes parents, epidemiologists and public health experts have recommended. Rather, classes will be combined and likely grow in size because the government has not funded lower class sizes.

In Edmonton, the city’s public school board said nearly 29,000 students, or roughly 28 per cent of its entire enrolment, had opted for online learning as of Wednesday, though the board stressed that those numbers could change. To accommodate them, it has assigned 775 teachers to those online students. The board has hired an additional 100 teachers on temporary contracts, but board chair Trisha Estabrooks said the shift has meant decreased in-class enrolment hasn’t led to a decrease in class sizes.

“Even though we have 30 per cent of our students choosing to learn online, the reality is that doesn’t decrease the overall class size either, because we also need to have teachers in place to teach those online cohorts,” said Ms. Estabrooks, who acknowledged that in many classrooms, physical distancing is difficult, if not impossible.

Atiba Ralph, a single Black father, said he has heard so far that all of his daughter’s friends will return to in-person classes this fall; he hadn’t even heard of learning pods but said they sounded like “a pretty smart idea,” albeit one that was out of reach for him.

“It probably happened with the people that are in a higher tax bracket,” he said. “I have a little bit more financial problems.”

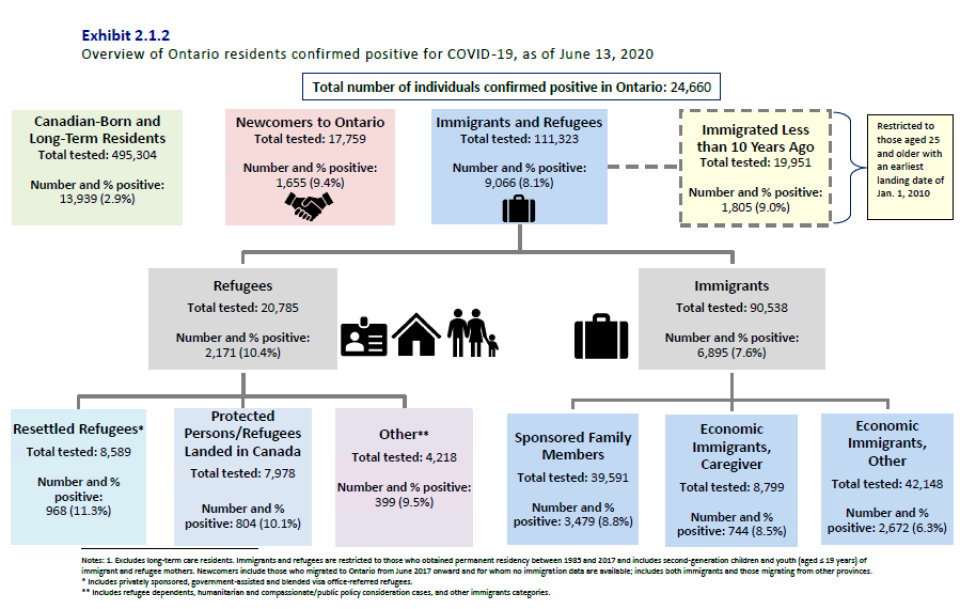

The COVID-19 threat is present every time he steps out of his apartment in Toronto: He lives in the Jane and Finch area, one of the most-infected in the city, and knows of two Black people – one a neighbour of his mother, another a friend of a friend – who died of COVID-19 earlier this year. Public health data collected by the city from mid-May to mid-July showed Black people had the highest share of COVID-19 infections.

Recognizing that some neighbourhoods have been much harder hit than others by COVID-19, the Toronto District School Board is directing extra funds and capping class sizes at abo

ut 80 schools in those areas, most of which are in the northwest corner of the city.

Alice Romo, an education advocate with the Latinx, Afro-Latin-America, Abya Yala Education Network, says she worries about the way children from low-income neighbourhoods will fall behind this year if they are educated at home: They’ll be less engaged, it will be more difficult for them to finish their homework and, crucially, many will miss out on all the non-academic parts of school that keep low-income communities afloat, such as breakfast and lunch programs.

“We’re definitely going to see this a few years down the road. There will be more of an inequality gap,” she said.

Those who withdraw from the system may think the decision only affects their household, “the more you shift the role of education towards families and away from public schools, the more inequality you’re going to have,” says Andrew Franklin-Hall, a philosophy professor at the University of Toronto who studies ethics.

For some students, school might be the only environment where they are exposed to peers from diverse ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds; in a learning pod, just like in a private school, opportunities for that exposure are limited.

“When parents are suddenly forced to make this kind of decision, naturally they turn to the resources they have, which is their own friends, their own community,” he said. “This is not the sort of thing that people feel comfortable articulating, because they don’t want to say, ’Well, I don’t trust the people who are different than me or I don’t trust the people who aren’t as well off or have a different race.’”

Before the pandemic forced a crisis in the education system, many school boards had committed to addressing systemic racism and inequity by re-evaluating programs, such as French immersion (which attracts a higher proportion of affluent, white students) and streaming (which routinely put Black children on a path to applied courses, which limit their options after graduation), that have disadvantaged students from low-income and racialized communities. Now with educators focused on the basics of opening schools, reimagining the system seems impractical, if not impossible.

In June, Stephanie Brembridge, a Black mother in Toronto whose son attends a public Catholic school, reached out to the school principal to ask whether she could add an item to the agenda for the next parent council meeting of the year: She wanted to discuss what the predominantly white school could do to better help Black and Indigenous students succeed.

Her faith in the school had already been tested. Her son, Trusten, had been suspended several times – once for apparently saying “an inappropriate word” – though the school was never able to tell Ms. Brembridge what that word was. With the help of an advocacy group that works with Black parents, she was able to get a few of those suspensions overturned (data collected at school boards across the country show that Black students are suspended and expelled at a disproportionate rate).

When it came time for the parent council meeting, which was held over Zoom, Ms. Brembridge noticed her item was at the very end of the agenda. She grew anxious as an hour and a half flew by, while the other parents (all but one of them were white) discussed which teachers were retiring, how they might safely plan a social function in the summer and other matters Ms. Brembridge believed to be far less pressing than hers.

“Okay, I think that’s it,” someone said, ready to adjourn the meeting. Ms. Brembridge, surprised, unmuted her microphone and reminded them she still hadn’t spoken. She was told she had three minutes and could see parents starting to leave the chat. “I‘m not going speak until I can get everybody’s full attention,” she said. Her item was moved to the agenda for the next meeting – three months later, in September.

As a teacher in Toronto, Kelly Iggers has been exposed to the type of parental advocacy that’s aimed at “achieving supports that will benefit one’s own child.” When she learned Ontario’s back-to-school plan, released in late July, would not include reduced class sizes, she started a petition arguing in favour of them that netted more than 250,000 signatures across the province and evolved into a campaign with parents, educators, doctors and others discussing and planning in closed groups, including a WhatsApp chat.

“This issue of advocating for a safe and equitable return to school, it’s not about advocating for one’s own community or one’s own child,” she said. “This only works if we’re advocating for something that’s going to support everyone.”

This moment of reckoning in Ontario comes at a time when Alberta is moving toward a model that could heighten class and race disparities within the public system. For now, it’s the only province to have charter schools, which are independently run, non-profit public schools that have a greater degree of autonomy than a normal public school, allowing them to create programming that’s only for girls, or for the academically gifted.

Earlier this week, the Choice in Education Act took effect that, among other things, makes it easier to apply for and create a charter school. Now, a group wanting to establish a new charter school can bypass the local school board and apply directly to the government.

Calgary mom Dallas Hall’s son started Grade 4 last month at Connect Charter School after switching from a local public school. Ms. Hall said she likes the type of education he’s receiving, which includes experiential learning and outdoor learning. She also said the school has less bureaucracy than a traditional public school system – the same features that are making private school or learning pods an attractive option for parents elsewhere. Ms. Hall likes the idea of parents having choice in education. “They should have a voice. Their voice should be welcome,” she said.

Ms. Iggers said she didn’t want to vilify parents who are choosing private options, but says this shift out of the classroom has the potential to cause long-term damage.

“It’s prompting families with the means to do so to leave the system,” she said. And when they leave, “they [take] with them what are often the most powerful voices to advocate for a properly funded education system.”