Douglas Todd: Canada’s many language schools ravaged by COVID-19

2020/10/31 Leave a comment

Yet another element of the immigration industry:

Downtown Vancouver might never look or feel the same, as scores of its English-language schools now sit empty with metal security gates across their doors. Many will never reopen.

B.C.’s once ultra-popular, private English-language schools, which last year enrolled 70,000 to 100,000 students, are concentrated in the city’s core. Each year language students from around the globe enlivened downtown cafes and street life, as well as rental and homestay units through the West End and Yaletown.

Most Canadians don’t give much thought to the often-overlooked English- and French-language industry, but if they did they would recognize COVID-19 has ravaged this formerly booming sector as badly as it has crippled airlines and international tourism.

The health measures brought in in March to secure borders against travellers who could carry the coronavirus into Canada caused upwards of 100 language schools in B.C. alone to close their doors to in-person classes. Some struggle just to offer low-cost online instruction to students spread through mostly Asia and Latin America.

Officials with Languages Canada, an umbrella group for more than 200 registered schools, forecast this summer that three of four of its member schools could be forced to permanently shutter. In Metro Vancouver alone, Languages Canada says their students, almost all from outside the country, were pumping more than $500 million a year into the economy.

Global Village Vancouver gone

More than 23 registered language schools across the country have already permanently packed it in, including Vancouver’s decades-old Global Village Vancouver. And that number doesn’t include the closings at many smaller private schools that are not registered with Languages Canada.

“Metro Vancouver has the most private language schools of any Canadian city. And many of them are never going to open again,” says Lorie Lee, a former language-school owner who has served on federal government trade missions and advisory panels who now works with a company called Guard.me that provides health insurance to international students.

“Not only do these schools employ many teachers and staff, the students stay with host families and rent apartments and spend money in restaurants and on car leases and trips to Whistler. That’s not to mention the schools themselves rent large amounts of space downtown.”

Language-school students often come to Canada, Lee said, with varied dreams about learning English, since it’s the common language of global business, aviation and science.

One-third of them, almost always financed by their parents, want to gain permanent resident status in Canada, Lee says. Another cohort aim to get English under their belt so they can be eligible to apply to a Canadian or American university.

Those who belong to a third group want to improve their English because it will enhance their careers in their homelands, Lee says. Many others seek adventure, learning a bit of English along with skiing, partying and hiking in a beautiful province.

There are several reasons private language schools have been hit harder by the pandemic than Canada’s public universities and colleges. The biggest problem is their rents.

High rents

Unlike public language schools, which are subsidized by taxpayers, private language businesses, especially those in Vancouver, are stuck having to pay high rents on five-year leases they normally can’t get out of. A typical monthly rent for a school downtown, Lee says, runs about $50,000 a month.

“These schools have had no students since March, so that’s eight months of no income and many are going into debt. Those schools closing will have an economic impact on other businesses, not to mention on the host families that relied on the international students to pay their mortgages.”

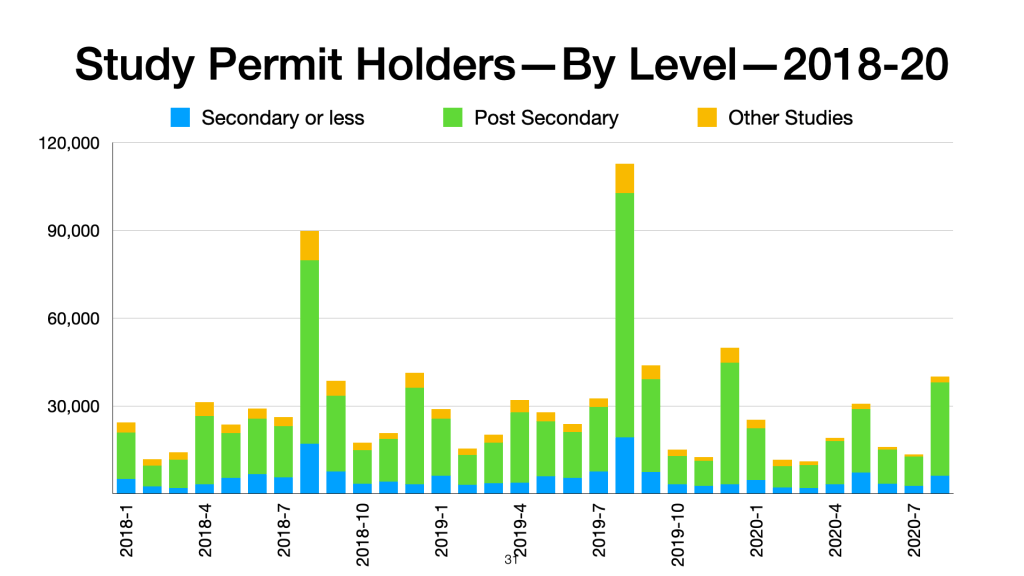

The second big dilemma is that language-school students are often in a different immigration category from the 642,000 people who last year were in the country on study-work visas so they could attend public institutions like the University of British Columbia, Simon Fraser University and Kwantlen Polytechnic.

Only a minority of private language-school students obtain such long-term study-work visas to be in Canada, Lee says. Most tend to be here on visitors’ visas, which last less then six months.

That means that Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s unprecedented move to reopen the border to foreign students on Oct. 20 is of only limited help to most language schools, since the bulk of their students will not be eligible.

Gonzalo Peralta, head of Languages Canada, has said Ottawa’s policy decision extends a lifeline to some private language schools. But Lee stresses that “even with Ottawa opening the gates, there are still going to be problems.”

It’s all having a little-discussed impact on Metro Vancouver. In 1991, when Lee first shifted from teaching English at UBC to launching her own school in Vancouver, her market research showed there were only seven private language schools in the city. “But,” she says, “when I sold my school in 2011 there were approximately 200 private language schools in Vancouver.”

Even though critics have condemned the way some private language schools are shoddily run and some Canadian economists worry they contribute to bringing more low-skilled workers into an already modest-wage job market, Lee generally remains a booster.

She’s excited that language schools bring so many students from Brazil, China, India, Vietnam, Japan, Mexico and South Korea. Four of five head to Ontario or B.C. This province has more than 50 schools registered with Languages Canada, the vast majority being private, employing about 2,000 staff and teachers until COVID-19 hit.

And, as Lee clarifies, Language Canada’s registered schools are only the tip of the language-industry iceberg. There are scores more non-registered private language schools in Metro Vancouver that, until the pandemic, served tens of thousands of pupils.

Glimmers of hope

Some publicly funded language schools and the larger private ones will likely be able to hold out until the end of the health crisis, Lee says. But even they are struggling just to keep afloat by offering online courses, only charging $99 a week. “Meanwhile, think of how expensive their rents are.”

There are glimmers of hope for some schools, Lee suggests, but their survival will likely rely on further easing up of immigration policy, border restrictions and COVID-19 safety rules, which restrict how many students will be allowed in language classrooms at one time.

Even though it’s frustrating to Lee, she recognizes why most Canadians rarely think about the plight of private language schools and their impact on the country.

With understatement she says, “I think most people in Canada don’t understand how the immigration system works.”

Source: Douglas Todd: Canada’s many language schools ravaged by COVID-19