Good long read, highlighting ongoing policy failure at both federal and provincial levels:

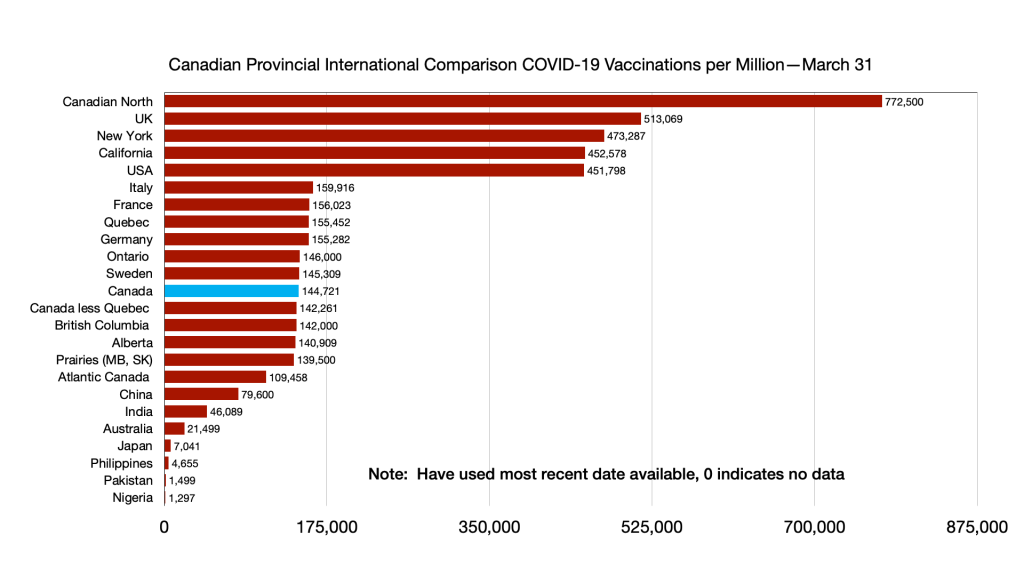

For weeks, Canadians have been casting their envious eyes to Israel, where more than half the country has been inoculated against COVID-19. Israel, less than a quarter the size of Canada, has administered nearly twice as many doses of the COVID-19 vaccine.

The Middle Eastern country has some innate advantages: It is small and centralized, and offered top dollar to ensure vaccines from Pfizer and Moderna would come fast, and in large volumes. But geography and money aren’t the reason why Israel is outpacing Canada by 10-to-one.

Israel has the vaccines because it has the data.

In its shrewd deal with Pfizer, Israel offered to turn the country into one giant clinical trial: Providing the vaccine manufacturer unprecedented large-scale visibility as to the vaccine’s efficacy. It’s all made possible because of the country’s state-of-the-art information technology and robust national vaccination database.

The rest of the world is currently benefiting from that incredibly granular information.

Canada could never have struck such a deal. Its health technology is, charitably, a decade out of date. It lacks the ability to adequately track infectious disease outbreaks, efficiently manage vaccine supply chains and storage, quickly administer doses, and monitor immunity and adverse reactions on a national basis.

Even though all the shipments of vaccines arriving in Canada come with scannable barcodes, to make tracking and logistics easier—with some manufacturers even barcoding the vials themselves—no Canadian province can scan them. In many provinces, pharmacies can’t access the provincial vaccine registry. Provinces do not automatically submit reports on COVID-19 cases or vaccines into the federal system, and must submit reports manually. Many crucial reports are still submitted by fax: Where fax has recently been phased out, they have been replaced by emailed PDFs.

Ours is a dumb system of pen-and-paper and Excel spreadsheets, in a world quickly heading towards smart systems of big data analytics, machine learning and blockchain. It’s unclear how Ottawa will be able to issue vaccine passports, even if it wants to.

At the core of the omnishambles is a simple fact that Canada has no national public health information system, but 13 different regional ones. Many of those regional systems have smaller, disconnected, systems within: Like a Russian nesting doll of antiquated technology.

But there’s good news: It doesn’t have to be this way. In some parts of the country, real progress is being made. Small technology start-ups are figuring out cheap, scalable and innovative solutions. In some provinces, progress can be as simple as updating operating systems.

If we are ever going to build efficient, cost-effective, and effective health infrastructure, Ottawa needs to take the lead. We need to abandon the idea that federalism requires us to have each sub-national government run entirely independent, walled-off, health databases.

We need data sharing. We need shared infrastructure. We need a national public health system.

***

For decades, Canada has been building out computer systems designed to track infectious disease outbreaks and vaccination campaigns. In non-pandemic times, that means monitoring the spread of sexually transmitted infections, keeping track of supplies of vaccines for things like influenza and mumps, and keeping an eye out for novel outbreaks of infectious diseases.

Most of the country relies on a public health system called Panorama, but not everywhere: Alberta, P.E.I., Newfoundland and Labrador, Vancouver Coastal Health, and the Public Health Agency of Canada itself all use other systems.

The provinces and territories that do have Panorama use it to varying degrees. From one province to the next, the heath infrastructure has different names, different features, unique customizations and varying capabilities.

This was never the plan. Canada, in fact, was once a world leader in digitizing its public health infrastructure.

In 1996, at a national conference of health officials, it was decided that “an immunization tracking system is urgently needed in Canada.” It included a list of goals: To identify children in need of vaccination, to book appointments, to do population-level analysis of immunity to diseases, and so on.

In 2002, basic national standards were drafted: “The time has arrived for a national program to be administered provincially, thus ensuring compatibility between provinces so that this health care information can be accessed when needed.”

When SARS hit Canada in 2003, before any of this technology could actually be implemented, health authorities found themselves woefully unprepared. The federal government and province of Ontario tried to manage the epidemic relying on “an archaic DOS platform used in the late 80s that could not be adapted for SARS,” per an Ottawa-commissioned report.

The country had only gotten a taste of what a deadly and hard-to-control infectious disease outbreak looked like. And it wasn’t ready. It only underscored just how crucial this national database was. The solution to that was Panorama.

It wasn’t cheap. Paul Martin’s government committed $100 million in its 2004 budget to seed the creation of Panorama, through the not-for-profit, government-funded Canada Health Infoway. His government also created the Public Health Agency of Canada to ensure there was central preparedness for the next SARS.

“With this budget, we begin to provide the resources for a new Canada Public Health Agency, to be able to spot outbreaks earlier and mobilize emergency resources to control them sooner,” then-finance minister Ralph Goodale said in his budget speech. He promised “a national real-time public surveillance system.”

The subsequent Harper government, seemingly recognizing the wisdom of what his predecessor had started, provided another $35 million more to fund the work. The contract to build this national surveillance system would ultimately go to IBM Canada.

In 2007, Canadian health officials flew to a conference in Florida to tell their American colleagues how far ahead we were on this health technology.

“By 2009 there will be a national surveillance system that will include a network of immunization registries,” their powerpoint presentation said. They broke down how it would work: A vaccinator would enter a patient’s information, scan the barcode on the side of the vaccine vial, and it would all go straight into the provincial database and, later, the federal system. A computer system could manage an outbreak from infection to immunity.

Dr. Robert Van Exan, who ran health and science policy at Canadian vaccine giant Sanofi-Pasteur, was tapped by Ottawa to figure out how to effectively barcode vaccines in the early 2000s.

“Technically, it’s a huge challenge,” Van Exan told me when I interviewed him in March for the Globe and Mail. “At least, it was.”

At the manufacturer, vaccines moved along a conveyor belt at a rate of about 300 to 1,000 vials per minute, he explained—adding new labelling was a logistical nightmare. But, within a few years, he had corralled the technological know-how to get it working. He went back to the federal government, excited that he and his company were part of this digital revolution.

“Canada was ahead on this by a decade,” Van Exan told me.

But through the late 2000s and early 2010s, that plan seemed to fall further away. There were delays and cost overruns, which largely fell to the provinces and territories. In 2015, British Columbia’s auditor general reported that the province had budgeted less than $40 million to build and maintain Panorama. The cost wouldn’t just double: It nearly tripled. The B.C. government alone would pay more than $110 million, not including ongoing annual costs.

As the program struggled, the Public Health Agency of Canada—the body specifically created following SARS to help build a national public health strategy—pulled out of Panorama. It let the provinces and territories fend for themselves. Nobody was left to actually enforce those brilliant minimum standards from years earlier. It stopped being a cross-compatible national system, administered provincially, and became a smattering of incompatible systems with no real national buy-in at all.

Provinces like Alberta bailed on Panorama in frustration.

The provinces and territories that stuck with it wound up with an inferior product. Beyond just the increased costs, the devastating report from the B.C. auditor general found that core components were just missing. Online vaccine appointments? Vaccine barcoding? Offline usage? Federal integration? All those features were promised, but “not delivered.”

“The system cannot be used to manage inter-provincial outbreaks, the main reason for which the system was built,” reads one particularly galling passage.

Other features didn’t work, or had severe limitations.

Van Exan recalls how “fed up” the vaccine industry was with Ottawa. “They went through this trouble to put the label on the vials,” he said. And for what?

“Despite a substantial federal investment,” one peer-reviewed study pointed out in 2013, “Canada continues to lag behind other countries in the adoption of public health electronic health information systems.” A 2015 study found that multiple provinces failed to even meet the minimum standards set out in 2002—standards that were already becoming stale and anachronistic.

Those 2002 national standards haven’t been updated since. (Health Canada told Maclean’s that the most recent standards were issued in 2020, although the document it pointed to clearly labels them as recommendations for new standards.)

Whether the standards are from 2002 or 2020 is somewhat immaterial. Ottawa doesn’t even know to what degree the provinces follow the standards.

The standards clearly call for Canada to have “reliable digital access and exchange of electronic immunization information across all health providers with other jurisdictions (including federal).”

In response to a question submitted in the House of Commons, Health Canada wrote last summer that “it is not possible for the federal government to know the details of any of the configurations of the provincial/territorial instances of Panorama in order to judge whether it meets a particular standard.” The Public Health Agency has not performed an audit of Panorama, the government added.

There are lots of reasons for the boondoggle. Many provinces and territories had competing priorities for what their health infrastructure ought to look like, and many balked at the idea of sharing data with Ottawa or even their neighbouring governments. “The provinces chose to do things independently,” said one source with knowledge of the system, who spoke on the condition of anonymity. Some provinces tried to make Panorama “too many things to too many people,” they said, and ended up with a system that disappointed everyone. That’s a common problem in Canadian technology procurement.

Part of the issue was the technology itself. Canada tried to stand up an ambitious IT infrastructure at a time when things like cloud hosting and barcoding capabilities were still expensive, clunky and hard to do on a large scale. But the core problem was a total lack of leadership. Ottawa pioneered the idea for a national registry, then walked away when things got hard.

Ontario family doctor Iris Gorfinkle has been calling for this national strategy for years. Last year, before we even saw our first vaccine, she warned in the Canadian Medical Association Journal that “it is imperative that we have the ability to provide potentially limited vaccines to those jurisdictions with higher disease rates to optimize vaccine distribution and coverage.”

I asked her why we haven’t been able to do this. She answered in a word:

“Inertia.”

***

In the last decade, provinces have had to make do. Alberta has modernized the legacy system it reverted to when Panorama went sideways. Ontario has tried valiantly to customize and upgrade Panorama until it resembled the system the province ordered.

Over time, however, Panorama did improve. By about 2017, IBM was finally adding those features that had been left off. It built out new data dashboards, integrated barcode scanning, and added APIs to make Panorama compatible with other systems. Most critically, Panorama went from a clunky program that could only run on designated computers to a cloud-based program that could be accessed by any laptop, tablet or phone.

Indigenous Services Canada, which administers some health services to First Nation communities, actually won an eHealth award in 2014 for its implementation of Panorama. One B.C. public health official lauded the agency’s work, saying it would allow health professionals “to better detect early signs of outbreaks by enabling sharing vital information between different public health related services providers.”

Some provinces, like Nova Scotia, upgraded Panorama into the new, more functional version. “One of the great things about Panorama in terms of helping in an outbreak is just having more timely access to information,” a prescient Nova Scotia provincial health official told CBC in 2019.

But it hasn’t been uniform: Ontario’s heavily customized system is running an old version of Panorama. Saskatchewan still hasn’t implemented core Panorama modules, like the one that tracks adverse reaction reports.

One source said provinces could enable its system to scan barcodes and health cards with a flip of a switch—several provinces, the source said, actually refused, insisting manual entry was more efficient.

Meanwhile, provinces and territories are still relying on manual data entry and spreadsheets to track inventory and shipments. Some jurisdictions are logging immunizations with pen and paper. A citizen can’t readily carry their immunization record from the Northwest Territories to Yukon.

Pharmacists in Ontario need to enter every immunization into two systems: once, into their own record management program; and again, into Ontario’s newly fashioned COVaxON, a front-end interface that is supposed to feed into Ontario’s outdated version of Panorama.

The inefficiencies are glaring. But it gets worse.

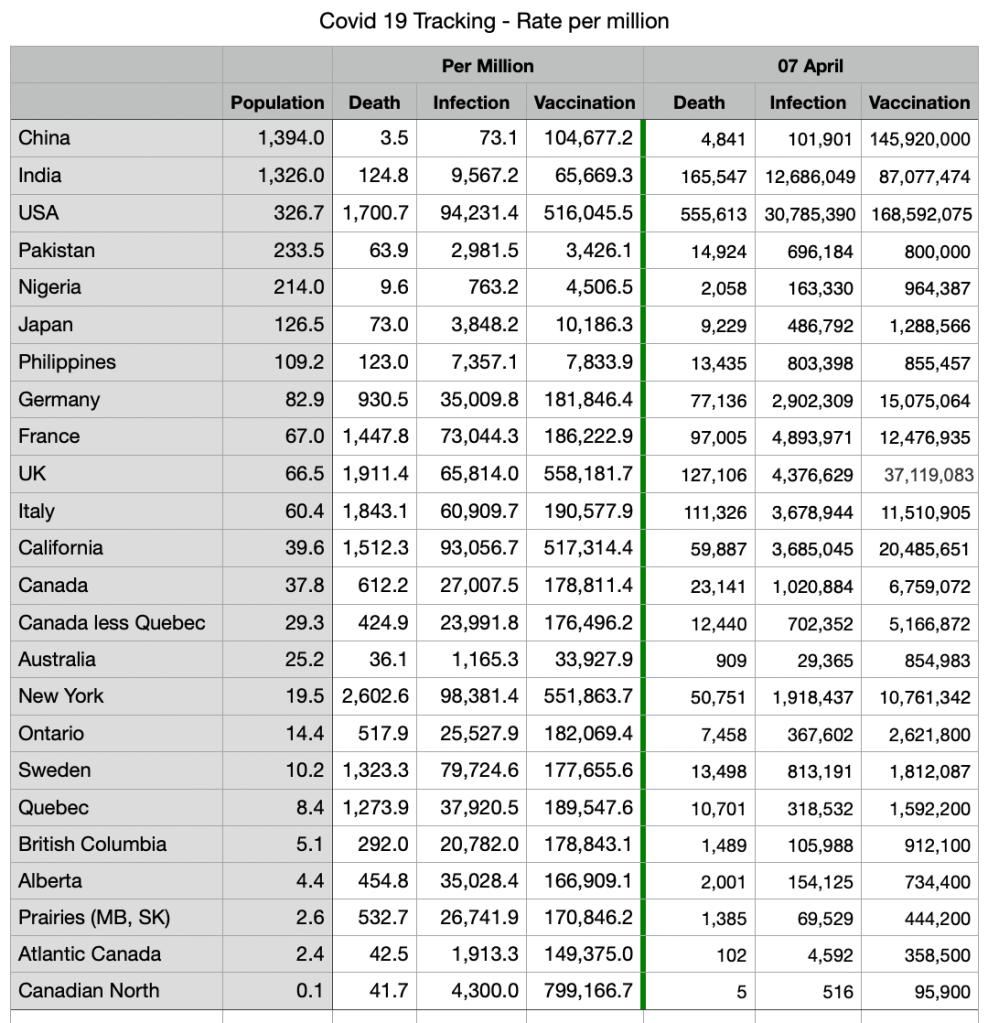

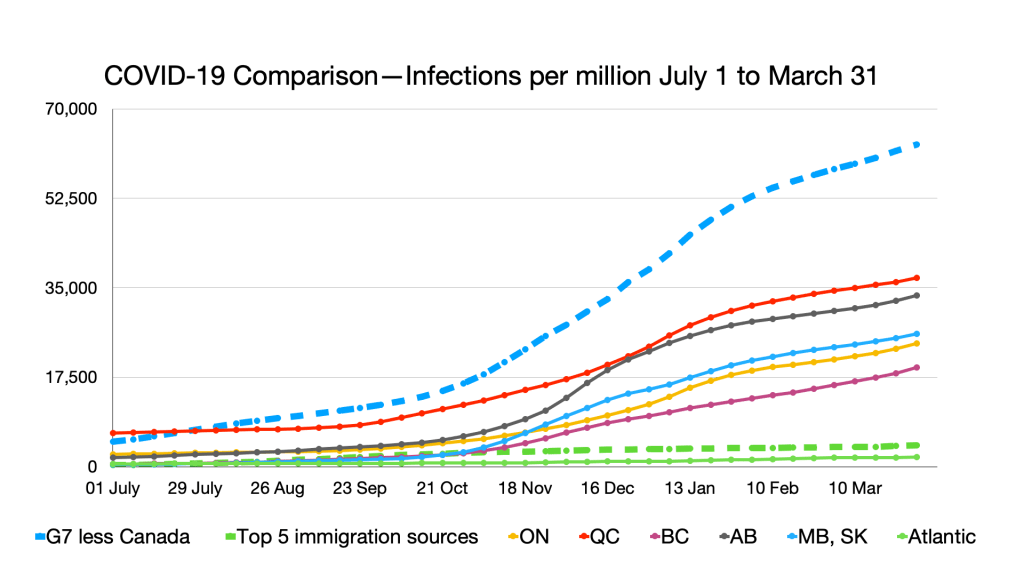

Notwithstanding inefficiencies and outmoded technology on the local level, the whole point of the Public Health Agency of Canada is to be able to track infectious disease outbreaks across the country. Right now, this is top of mind, as we wait to see the countervailing impacts of the COVID-19 variants and vaccines. A good system should be able to show us how different variants are spreading, and whether any or all of the vaccines are effective against which strains. But that only works if PHAC has the data.

Ottawa technically has information-sharing agreements with the provinces, but a government response to a question filed by Tory MP Scott Reid exposes how archaic the infrastructure truly is. Ottawa “does not have automatic access to data held in [provincial and territorial] systems, including Panorama,” the government wrote. “In the early weeks of the outbreak, some provinces were sending case information to PHAC via paper.” For the first four months of the pandemic, Ottawa wasn’t even collecting basic data on COVID-19 cases, like ethnicity, dwelling type, or occupation. Things have improved somewhat: Provinces now submit their reports manually, via a web portal.

The Public Health Agency of Canada reported that its “emergency surveillance team receives electronic files in .csv format from provinces and territories.”

A March report of the federal auditor general found that “although received electronically from provincial and territorial partners in the majority of cases, health data files were manually copied and pasted from the data intake system into the agency’s processing environment.” The audit also reports that many aspects of Ottawa’s data sharing agreements with the provinces and territories are not yet finalized. The audit further found that crucial information about COVID-19 cases—such as hospitalizations and onset of symptoms—was often not being reported to Ottawa.

The auditors came to a similar conclusion to many experts, like Gorfinkle and Van Exan: “We found that for more than 10 years prior to the COVID‑19 pandemic, the agency had identified gaps in its existing infrastructure but had not implemented solutions to improve it.”

When it comes to any vaccine, there are reports of adverse reactions—while they are rare, the recent panic over the AstraZeneca vaccine and blood clots shows this tracking is absolutely crucial. When a Canadian reports an adverse reaction to any vaccine, the province must pass it onto PHAC—which must, in turn, send it to the World Health Organization. Until very recently, Ottawa required that provinces and territories submit those reports via fax. More recently, it has modernized: “provinces and territories submit data [on adverse reactions] in a variety of formats, including line list submissions and PDF submissions,” the government said. That still means the reports must be entered manually. Some provinces only submit their reports weekly.

Panorama, meanwhile, has an adverse reaction tracking and reporting feature. PHAC just hasn’t been using it.

PHAC insists it has “well-developed surveillance and coverage information technology” and it responded to the auditor general with further more promises to address the gaps it has been vowing to fix for a decade. It’s hard to know if that progress is real or not.

In November—already some eight months into the pandemic—the federal government sent a secret request for proposals to a shortlist of pre-qualified suppliers looking for a “mission-critical system” to manage vaccine supply chains, inventory, and to ”track national immunization coverage.” The $17-million contract went to Deloitte, and it is supposed to plug into the disparate provincial systems to provide some semblance of a national picture. But Ottawa is refusing to disclose any timelines, details of the project or really anything beyond some boilerplate talking points. We only know about the project because the request for proposals was leaked to me in December. (“It’s awe-inspiring that they would withhold that information,” Gorfinkle says. I agree.)

So long as we commit to this madly off in all directions strategy, Ottawa can’t build a functional national system. Federal agencies can’t coordinate, much less individual provinces and territories. The patchwork makes national visibility impossible. Worse than a garbage-in, garbage-out problem—provinces can’t even agree on how to format the garbage. The result has been error and inefficiency.

One Ontario woman was hospitalized after receiving three doses of a COVID-19 vaccine, two of them just days apart—something that would never happen if she had an accessible, up-to-date vaccination record.

Meanwhile, seniors have been forced to stand in line for hours in Toronto, as health staff waste time doing work that could be easily automated. Epidemiologist Tara Gomes tweeted that her mother “had to repeat her address so many times to the person at check-in that she finally asked for a pen and paper and wrote it down.” It gets more frustrating when you realize, as Gomes noted, that her mother had to provide her personal information to get the appointment—the province’s COVaxON booking portal doesn’t connect to the COVaxON vaccine registry.

“You can’t blame one government,” Van Exan says. Every level of government of every political stripe has let this Frankenstein’s monster of a digital health system continue to limp along.

”Including the current one.”

***

The barriers to improvement are lower than you might think.

There is no particular reason why Vancouver ought to be using different vaccine management software than Victoria, or why Toronto should be running a different version of Panorama than Halifax. The diseases these health authorities face are the same, as are the vaccines dispatched to combat them.

Ottawa seems, a year after the start of this wretched pandemic, to be coming around to that idea. The Public Health Agency of Canada told Maclean’s it will finally be adopting Panorama, which “will enable more automated and timely data sharing and reporting.” At the end of March, it wrote that the new system “is expected to be online in the coming weeks.” Deloitte, IBM and the Government of Canada have been working together to get Panorama working with the Public Health Agency’s existing systems.

But just adopting Panorama isn’t nearly enough.

Step one is deciding if we really want a national system. If the provinces and territories are truly, completely incapable of running a system to national standards—or Ottawa is incapable of managing those standards—then maybe we should actually commit to decentralization. Shut down PHAC and download money and responsibility for public health to the provinces.

The benefits of a national system, however, are real and obvious. If we can agree with that principle, then step two is picking a technology and sticking to it.

We shouldn’t be married to sunk costs: If there is a better system out there than Panorama, we should consider it. But actually committing to Panorama is the obvious choice. It is already the standard for most of the country, and there’s no guarantee that starting from scratch will rectify our jurisdictional issues. What’s more: A list of other countries are now relying on Panorama. The more customers, the better.

Sticking with Panorama doesn’t mean that Alberta and Vancouver need to abandon their proprietary systems—but it does mean they need to be speaking the same language.

To that end, step three is standardizing data collection and sharing.

This, of course, needs to be done wisely: Patient data should be anonymized, for security reasons. Any cloud systems must have their servers within Canada (Nova Scotia’s data is available on the cloud, but entirely located in Halifax and Quebec.) And we need to make sure that governments are entirely transparent about how, when and why they use this aggregated health data. But all those jurisdictions need to use the same file formats, collect the same variables, and report them in the same efficient, automatic, manner.

Step four is investing in the infrastructure we need to make all this work—and sharing resources where that makes sense. If health authorities need an app to scan barcodes to track shipments, it doesn’t make sense for every province and territory to be using a different app. If we need to buy barcode scanners, every province should be buying the same one. Where it makes sense to share servers, we should share servers.

Step five is the easiest: Keep things current. It’s hard to think of any other instance where relying on 20-year-old technology standards makes sense. We need to be constantly revising and updating how we handle infectious diseases—the benefits will be apparent, in how we tackle everything from mumps, to HIV, to the next highly infectious disease that reaches our shores.

Again, these things are very doable, and don’t require any government to sacrifice autonomy. And, best yet, it can save us money.

On barcoding alone, a government panel estimated in 2009 that Canada would see $1 billion in savings by saving time, preventing wastage and reducing errors. On virtually every other front: Struggling through antiquated IT, and relying on overworked health staff to make up the difference, is expensive.

Governments don’t have to do it alone, either. Private industry can help.

In Alberta, start-up Okaki devised a simple, scalable system that can manage vaccination campaigns and even scan vaccine barcodes. The company has been running immunization drives for years, mostly in First Nations, and feeds its data directly into the provincial system—it is also compatible with Panorama.

CANImmunize, which began as an app allowing individuals to track their own vaccination record, now does many of the things Canada’s national system was supposed to do—including tracking appointments, monitoring adverse reactions, scanning vaccine barcodes. The technology can be fully integrated with Panorama.

Since I began writing about this issue for the Globe and Mail, my inbox has been inundated with emails from companies insisting that they could fix these problems in no time at all. There is no shortage of qualified people looking to help, and to innovate.

A group of companies, led by IBM, recently won a contract to build Germany’s vaccine passport system. It will use blockchain technology to make citizens’ vaccination records accessible, secure and verifiable. If we don’t get our act together soon, Canadians will be lucky to even get laminated paper vaccination records.

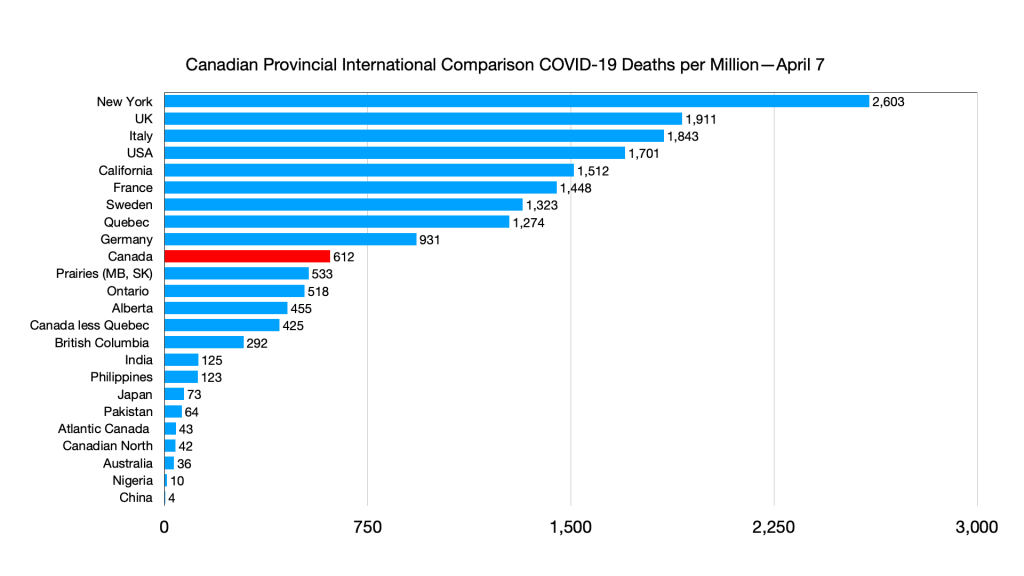

The provinces and territories need to come to the table and do this together. Our self-injurious commitment to federalism at all costs is endangering our own citizens. Because every province plays in their own needlessly walled garden, they are less prepared to deal with epidemics, they are less efficient at administering vaccines, and their citizens are more at risk from getting sick and dying.

Our country is supposed to be one of cooperative federalism, where provinces and territories can pursue creative solutions to unique problems. But when it comes to the basic mechanics of infectious disease outbreaks, there is no central leadership.

COVID-19 does not change shape when it crosses from Manitoba to Nunavut. We need the same set of tools in every province, or else we’re never going to fully beat this virus—and we’re going to be dangerously ill-equipped for the next one.