Dave Snow: The Canadian Human Rights Tribunal will not be able to handle the deluge of cases from the Online Harms Act

2024/08/07 Leave a comment

Interesting analysis of their workload and decisions:

…Exploring Human Rights Tribunal decisions

To determine how this new Bill could affect the federal human rights framework, I sought to understand how the existing framework works in practice. I conducted a content analysis of every Canadian Human Rights Tribunal decision over the last five-and-a-half years, from January 1, 2019, to June 30, 2024.

Surprisingly, I discovered that the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal issues very few decisions. Between 2019 and 2024, the tribunal only issued 63 actual decisions, along with 260 procedural “rulings” about ongoing hearings—typically involving brief motions to admit evidence, anonymize participants, or amend statements.

Moreover, nine of the 63 decisions were merely procedural in nature (mostly dismissing “abandoned” complainants) and one evaluated compliance with an ongoing settlement agreement between First Nations and the government of Canada.

This means that since 2019, the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal has only actually issued 53 decisions that involved an evaluation of a complaint alleging discrimination or harassment—fewer than 10 per year–from a low of six in 2022 to a high of 14 in 2019. By way of comparison, in 2023 alone, human rights tribunals in Alberta, B.C., and Ontario issued 126, 248, and 1,829 decisions respectively. The COVID-19 pandemic did not appear to have a serious impact on delaying tribunal decisions.

In human rights tribunals, complainants allege discrimination or harassment based on one or more “grounds.” They can claim to have faced discrimination on multiple grounds simultaneously. Across the 53 decisions, there were an average of 2.1 grounds claimed per decision.

The most frequently claimed ground was disability (in 58 percent of decisions), followed by national or ethnic origin (34 percent), race (32 percent), family status (21 percent), age (19 percent), and sex (19 percent). Interestingly, there were only two decisions where complainants alleged discrimination based on religion, only two on sexual orientation, and only one on gender identity.

For each decision, I examined whether the claimant was successful (a “win”) or unsuccessful (a “loss”). I characterized partially successful claimants as a win, as these decisions still involved a remedy that typically included some form of financial compensation.

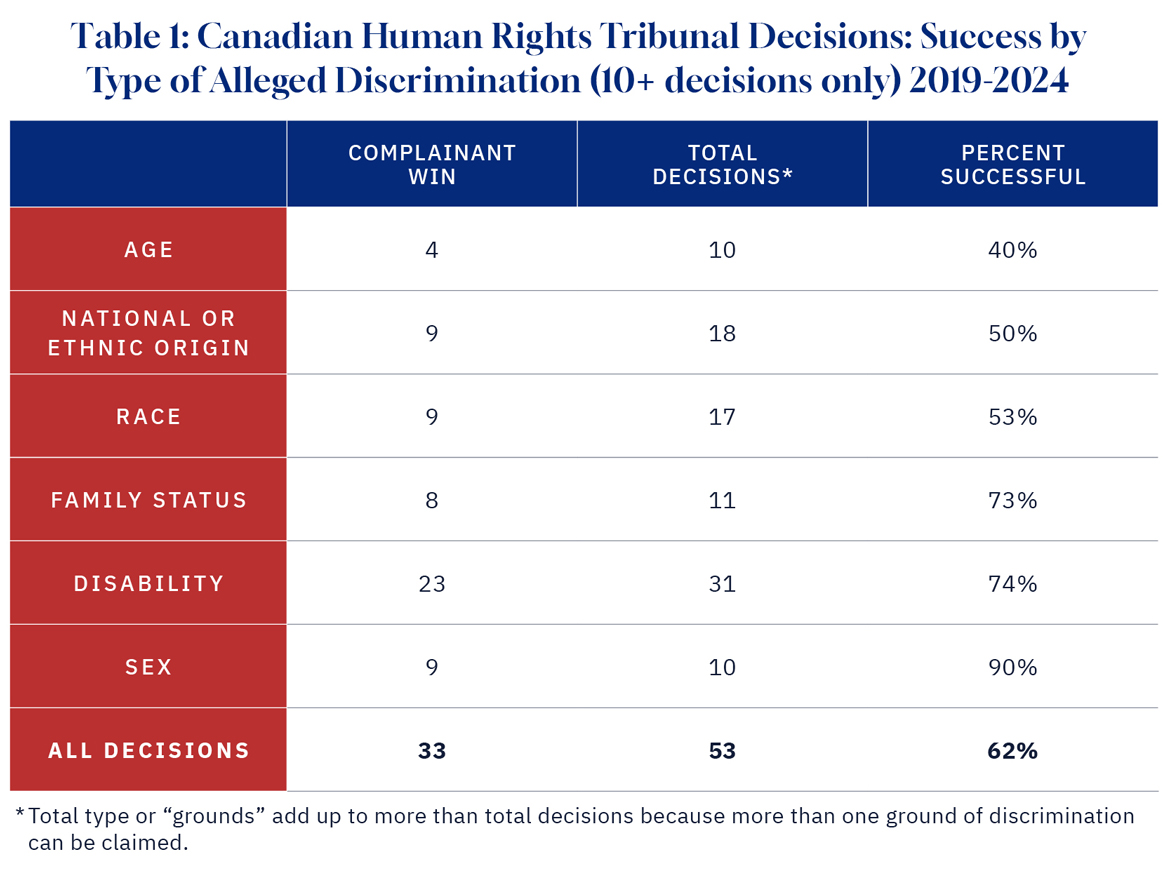

Table 1 shows an overall success rate of 62 percent. It also shows the win rate for each type or “ground” of discrimination that appeared in at least ten decisions.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

I found that complaints alleging age-based discrimination—all but one of which were based on old age —were least likely to be successful (40 percent win rate). Complaints involving discrimination based on race (53 percent) and national or ethnic origin (50 percent) also had a lower-than-average success rate.

By contrast, complainants alleging sex-based discrimination or harassment were the most successful (90 percent). Nine of the 10 complainants alleging sex-based discrimination and or harassment were women. Eight of those nine were successful.

Table 2 organizes the 53 decisions according to the three types of “respondents,” or the organizations accused of harassment or discrimination: federal government entities (including federal departments, Crown corporations, the RCMP, and the City of Ottawa); private companies in federally-regulated industries (transportation, aviation, marine, rail, banking, and telecoms); and First Nations. There was minimal variation in success rates by the type of respondent, with complainants slightly less successful against First Nations (58 percent win rate) than against governments (64 percent) and private companies (63 percent).

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

Given the controversy over the incoming chief of the Canadian Human Rights Commission, I also sought to explore decisions in which Jewish complainants alleged antisemitic discrimination, whether on the grounds of religion or national or ethnic origin.

What I found was that there were no such decisions. The words “Jew,” “Zion,” “Zionist,” and “antisemitic” do not appear in any of the tribunal’s 63 decisions from 2019-2024. The word “Jewish” only occurs in four procedural rulings. Three were from an identically-worded sentence in procedural rulings describing an ongoing case involving an inmate who “self-identifies as an Indigenous, Jewish, Two-Spirit transfeminine woman”. The fourth was found in an interim ruling for a Muslim inmate. He had complained that Correctional Service Canada “provided a religious diet for Jewish inmates, but not a diet for [him] that would accommodate his Muslim beliefs and his health issues.”

It is worth noting how infrequent claims of religious discrimination are. Only two of 53 decisions involved religious discrimination, and in both cases the complainants also alleged discrimination on other grounds. Both complainants were successful.

Conclusions

Federal human rights institutions are under the political microscope, and for good reason. The Canadian Human Rights Commission claims“We must all call out antisemitism” but its incoming leader (expected to take up his post this week) once posted that “Palestinians are Warsaw Ghetto Prisoners of today.” Its website proudly displays a section on “Anti-racism work” yet it has been publicly admonished for its own alleged anti-black racism.

Meanwhile, as I have demonstrated through my investigation, the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal appears unprepared to deal with the influx of complaints about online hate speech for which it will be responsible if the Online Harms Act passes.

Based on my research, I draw three main conclusions. First, the tribunal simply does not issue many decisions. It only issued 63 decisions over the last five-and-a-half years, 10 of which did not involve a formal evaluation of discrimination or harassment. The fact that the tribunal also issued 260 procedural rulings during the same period further suggests its existing hearings are often slowed down by procedural issues.

Second, the few decisions the tribunal does render are fundamentally different than what it would decide under the Online Harms Act. More than one in five decisions (12 of 53) involved truck drivers or trucking companies. The same number(12 of 53) involved allegations of discriminatory conduct by First Nations, such as when a non-Indigenous woman alleged discrimination for being fired from a First Nation-owned bowling alley (she lost). Cases of discrimination involving religion, gender identity, and sexual orientation are virtually nonexistent. The term “hate speech” occurred precisely once in a single decision over the last five-plus years. Not a single decision involved a Jewish complainant and only one involved a Muslim. This is not an organization prepared to adjudicate hateful content over the entire internet.

Third, it appears the Online Harms Act is yet another example of the Trudeau government asserting federal authority where provinces are likely better suited to govern. Because they deal with most forms of employment discrimination, provincial human rights commissions and tribunals have a far wider scope of jurisdiction than the federal tribunal does. Provincial human rights codes already deal with discriminatory speech, and the B.C. Human Rights Commission has even recently argued that the B.C. tribunal has jurisdiction over online speech as well. There is no inherent reason that the responsibility for determining online hate should be done by an entirely new and costlylayer of federal bureaucracy, particularly given the existing institutional capacity at provincial commissions and tribunals.

To be clear, I am not suggesting that provincial human rights tribunals ought to be given the sweeping powers contemplated by the Online Harms Act. Others have convincingly shown that the bill likely violatesCharter rights, and will chill “legitimate expression by the mere spectre of a complaint.” I am simply arguing that there are additional procedural reasons to be concerned about the institutional venues through which that chilling will occur.

Adjudicating online hate speech under the Online Harms Act will require deft sensitivity to competing rights claims and societal interests, a tall order for any organization. Instead, the federal government is placing its hopes in the hands of institutions that lack both the moral authority and institutional capacity to do the job.