Immigration and natives’ exposure to COVID-related risks in the EU | VOX, CEPR Policy Portal

2021/09/02 Leave a comment

Interesting assessment that immigrant workers in EU countries helped non-migrants avoid COVID-related risks given that immigrant workers filled the more difficult and dangerous jobs and that native workers were more able to shift to jobs that could be filled from home:

In recent years, immigration policy has been at the forefront of political debates in high-income destination countries. The UK completed its withdrawal from the EU on 31 January 2020, due in part to the desire to have more control over its immigration policies and to limit migrant flows. Intense political debates and polarisation on immigration helped fuel the rise of right-wing parties in Europe and political controversies over the border wall and the Dream Act in the US.

Despite these high-profile examples of the popular and political backlash against immigration, the academic literature provides evidence that immigrant workers often fill difficult and dangerous jobs that locals are not willing to undertake (Orrenius and Zavodny 2009 and 2013, Sparber and Zavodny 2020).

The recent COVID-19 shock exerted unforeseen and sudden pressures on labour markets across the world. While the negative effects of the pandemic were widespread, some categories of workers were hit much harder than others due to their occupations (Adams-Prassl et al. 2020a and 2020b, Dingel and Neiman 2020, Garrote-Sanchez et al. 2020, Gottlieb et al. 2021). Migrant workers, in particular, have been more exposed to the negative impacts of COVID-19 (Basso et al. 2020, Borjas and Casidi 2020, Fasani and Mazza 2020 and 2021). Another strand of the migration literature shows that in response to immigration, native workers reallocate to different occupations in which they have a comparative advantage (Peri and Sparber 2009).

Against this backdrop, a question of interest is whether immigration contributed to reducing locals’ exposure to the COVID-19 pandemic. In a recent paper (Bossavie et al. 2020), we explore how the prevalence of immigration in a labour market affects different types of workers’ exposure to COVID-19 related risks. We provide evidence that not only were immigrant workers more exposed to the economic and health-related shocks of the pandemic; they also served as a protective shield for native workers. By selecting into higher-risk occupations prior to the pandemic, immigrants enabled native workers to move into jobs that could be undertaken from the safety of their homes or with lower face-to-face interaction with customers and co-workers during the pandemic.

To assess the exposure of immigrant and native workers to the economic and health risks posed by the pandemic, we construct various measures of vulnerability. We look at three main dimensions of occupational vulnerability in the context of COVID-19: whether an occupation can be carried out from home, whether it has been categorised as essential by governments in the context of COVID-19, and whether it is exposed to COVID-19 health risks. In general, lower-skilled occupations such as machine operators, waiters, and day laborers tend to be less amenable to work from home than professional and managerial occupations. Essential jobs are concentrated in key sectors such as healthcare or agriculture. The higher health risks are found in essential occupations that require intensive face-to-face interactions such as doctors, personal care workers, or bus drivers.

We focus on destination countries in Western Europe, including the 15 countries that were the initial members of the EU (prior to the 2004 enlargement), Norway, and Switzerland. This region is the destination for an estimated 60 million of some 272 million immigrants worldwide. The analysis is based on a harmonised labour force dataset (EU Labor Force Survey) that contains detailed information on personal characteristics (such as age, education, occupation, and sector) of native workers and labour migrants in hundreds of local labour markets in subregions within European countries.1 The distribution of occupations by type of exposure to COVID-19 and by migrant status in the EU is reported in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Relative size of telework, essential, and non-face-to-face jobs in the EU

Source: Own calculation based on EU-LFS 2018 data, following EC directive (2020) and Fasani and Mazza (2020).

We first find that immigrants are generally employed in occupations that are more vulnerable to COVID-19-related risks (Fasani and Mazza 2021 report similar findings). Our estimates show that only 27% of employed migrants in the EU15 have a job amenable to telework, compared to 41% of native workers (Figure 2). On the other hand, migrants are slightly more likely to be in essential occupations. Combining those two categorisations of job vulnerabilities, migrants are more than 10% less likely than natives to hold jobs that are shielded from negative income shocks associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, migrants are also more likely to have jobs that are exposed to health risks, though we report significant heterogeneity in exposure among immigrant groups. The higher vulnerability of migrants is common across skill levels but varies depending on country of origin, with Eastern European migrants being the most exposed to income risks while migrants from Western Europe or North America have a similar risk profile to natives. Recent Eurostat statistics show that the higher vulnerability of migrants to the COVID-19 shock in Western Europe resulted in higher employment losses in 2020 (4% drop vis-à-vis 2019, compared to 0.8% fall for natives during the same period).

Figure 2 Share of workers by region of origin and risk type

Source: Own calculation based on EU-LFS 2018 data, following EC directive (2020) and Fasani and Mazza (2020).

We then examine whether the presence of immigrants in local labour markets has a causal impact on the vulnerability of native workers in the same geographic areas. Our empirical analysis is motivated by a general equilibrium model of comparative advantages in task performance between immigrant and native workers (Peri and Sparber 2009). In the model, native workers reallocate to other occupations in response to an influx of immigrant workers. In the empirical analysis, we use an instrumental variable approach to account for the non-random location choices of migrant responses to local job opportunities, which is based on past migration presence in the same region. Because of information, networks, and preferences, there is a strong positive association between current and past immigrant presence across European regions, as immigrants tend to move to the same locations where previous immigrants from the same country already live.

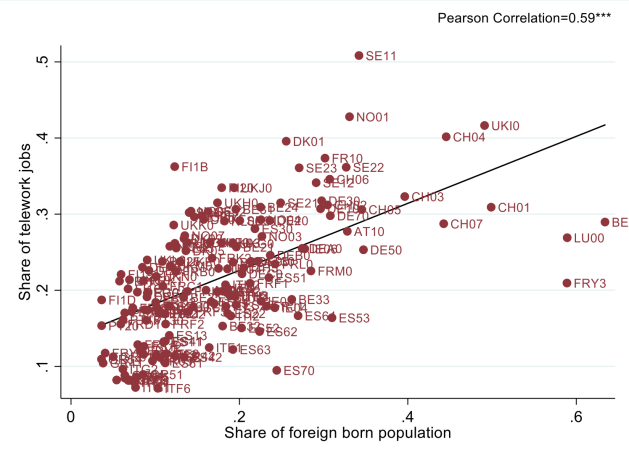

We find that native-born workers in those European subregions with a higher share of immigrants are significantly less likely to be exposed to various dimensions of occupational vulnerability associated with COVID-19. This association is especially strong when looking at the likelihood of being employed in teleworkable occupations (Figure 3), and the results get stronger once the endogeneity of immigrants’ location choices is taken into account. Immigration thus had a causal impact in reducing the exposure of native workers to some labour markets risks associated with the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 3 The relationship between share of immigrants in the working-age population and share of natives employed in jobs amenable to work from home in European regions

Source: Authors’ calculations using the EU Labor Force Survey 2018.

Note: The sample includes NUTS-2 regions from the EU-15 as well as Switzerland and Norway.We also find heterogeneous effects depending on the characteristics of native workers. The effects of immigration on job safety are stronger for highly (i.e. tertiary) educated native workers, who benefit from the presence of both high-skilled and low-skilled migrants. By contrast, the effects are smaller and statistically insignificant for less (i.e. non-tertiary) educated native workers. We also assess whether these compositional effects on employment of certain types of native workers are accompanied by overall changes in total employment and wages. We find no evidence of wage or employment impacts among native workers, suggesting that the increase in job safety among native workers is driven purely by their reallocation from vulnerable jobs to safer jobs.

In short, we find that immigration to Western Europe reduced the economic exposure of natives to COVID-19 related labour market shocks by pushing them towards occupations that are more amenable to work from home. Our paper thus provides another example of immigrant workers in effect ‘protecting’ native workers by taking on the riskiest jobs during the pandemic.

Source: Immigration and natives’ exposure to COVID-related risks in the EU | VOX, CEPR Policy Portal