‘It’s a lot of lip service’: Black federal public servants hope ‘Floyd effect’ will finally drive change as anti-racism movement grips Canada

2020/06/16 Leave a comment

Didn’t know that the Public Service Employee Survey allowed this desegregation (not on public site so assume was special request).

Useful:

Black public servants, already more likely to report being victims of racial discrimination than the rest of the federal bureaucracy, are hoping the “Floyd effect” will help drive the changes for which they’ve spent years trying to gain traction.

“In some ways, this has had a positive effect in the amount of interest that it has generated and, you know, white people being woke for a moment in time about the realities of being Black in Canada and the rest of North America,” said Richard Sharpe, founder of the Federal Black Employee Caucus (FBEC).

Mr. Sharpe and FBEC have been inundated in the last couple of weeks with calls to speak to and help departments generate ideas to address anti-Black racism in their various organizations.

The documented killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, Minn., by a police officer has affected white people and moved them to action to a scale Mr. Sharpe said he’s never seen in his lifetime. “We really feel a shift and we’re hoping to take advantage of that to make some progress on this work, maybe faster progress now that there’s some doors that have been opened for us,” he said.

Established in late 2017, FBEC’s primary objectives since its inception have been to get disaggregated employment equity data collected so that employees, employers, and policy-makers can all understand the landscape for Black federal bureaucrats, and to provide an element of support and unity for Black employees who are facing harassment and discrimination in the workplace.

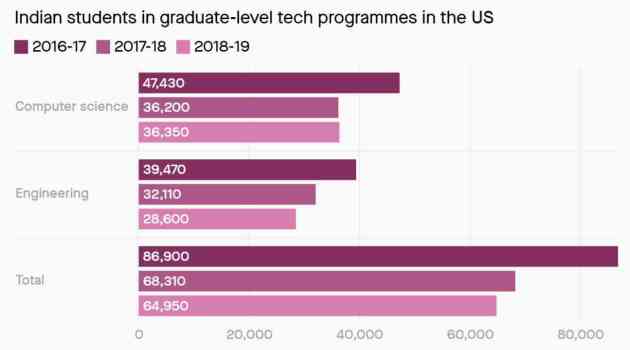

It’s an issue Black public servants have long been raising, but now they’re starting to get some data to back it up. Last year, the annual Public Service Employee Survey for the first time allowed respondents to self-identify as a specific visible minority group, instead of all being lumped in to one category.

In a February interview with The Hill Times, Mr. Sharpe said FBEC had a role to play in making that happen. In the lead-up to the 2019 survey, the group met with 25 to 30 deputy ministers across the public service, he said, as well as the Public Service Management Advisory Committee.

Fifteen per cent of Black employees indicated they had been a victim of discrimination on the job in the past 12 months, compared to 11 per cent of non-Black visible minorities, and only eight per cent of the public service, overall.

Of those who said they had experienced discrimination, 75 per cent of Black employees said it was racial, compared to 52 per cent for non-Black visible minorities, and 26 per cent for the public service overall. A little more than half of the Black respondents who said they faced discrimination (54 per cent) said it was due to colour (30 per cent for non-Black visible minorities, 16 per cent overall). Black public servants who said they experienced discrimination were less likely than non-Black visible minorities to indicate it was discrimination based on national or ethnic origin—34 per cent of Black employees compared to 43 per cent for non-Black visible minorities.

For FBEC, the results were not surprising. Mr. Sharpe pointed to the fact that there are more than 13,000 people who Statistics Canada had said identified as Black who were working with or for the public service (including contractors). A little more than 6,200 of the 182,306 PSES respondents in 86 departments self-identified as Black in the survey, which was conducted between July 22 and Sept. 6, 2019.

Treasury Board President Jean-Yves Duclos (Québec, Que.) said the statistics are “proof that more information is not only needed, but is useful.” Speaking to The Hill Times after addressing FBEC’s Feb. 24 annual general meeting, Mr. Duclos said it’s “good news” that employees are now able to self-identify in the survey. “We can therefore work better and more effectively to address the challenges that are revealed by the study.”

Mr. Duclos said the numbers themselves, however, are “absolutely unacceptable,” and that the underlying conditions will be better understood with the data.

“And not only will we understand those conditions better, but we will also have the obvious responsibility to address those challenges, to make sure that things are changing,” he said. “Things have improved over the last years, but there is a lot more work to do and we’re totally committed to do it.”

In his remarks, Mr. Duclos—who hired the Trudeau government’s first Black chief of staff, Marjorie Michel—spoke of the federal government’s “broad policy and legislative framework” to support diversity and inclusion in the public service. Asked if, based on the baseline numbers of discrimination in the public service, there needs to be not a broad policy, but a very specific one for Black employees, Mr. Duclos said that in his current and previous portfolio (he was the families, children, and social development minister in the 42nd Parliament) he frequently observed that diversity was not only a matter of justice and equity, but also one of efficiency, and led to better decision-making and better implementation those decisions.

“And the fact that Black employees tell us they are unable to be at their full potential is something of great concern to us,” he said. “I will certainly address those concerns and make sure that every federal employee, including Black employees, has the ability to make the fullest impact on our society.”

Black public servants ‘disappointed’ in lack of message from PCO

In the wake of Mr. Floyd’s death and the protests against anti-Black racism and police brutality that have exploded around the world, Mr. Sharpe said there was some disappointment that there hadn’t been any outreach or direct message of support for Black public servants from the top voices—including Privy Council Office Clerk Ian Shugart—despite an ask from FBEC.

FBEC held a general call with about 200 Black employees across the country on June 5. “A large majority of people—because we just let people talk about how they were feeling—felt quite hurt and disappointed that there was no message coming out on the part of the public service in support of them,” Mr. Sharpe said.

Mr. Sharpe said some departments and deputy ministers have taken the initiative and sent out messages, including Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada, whose associate deputy minister, Caroline Xavier, became the first Black woman to work at that level of the public service in February.

Mr. Duclos’ office did not respond directly to a question about whether the minister has reached out to Black public servants specifically in the weeks since Mr. Floyd’s death.

Another key member of the deputy minister community, Public Services and Procurement Canada’s Bill Matthews, also communicated his support to Black bureaucrats, Mr. Sharpe said.

Earlier this year, Mr. Matthews was named the Deputy Minister Ally for the UN Decade for People of African Descent within the public service. FBEC approached him for the role, which Mr. Sharpe said is necessary for the work they’re doing to be sustained at the executive level.

“I’ve been in government long enough to know that when the moment is done, and you don’t have presence around senior management tables on a regular basis, then you’re easily forgotten, and there’s another priority or another crisis that comes in and takes your place,” said Mr. Sharpe.

Though Mr. Matthews is “a white dude that doesn’t really have an equity background,” he has been supporting FBEC in a “full-throated way,” said Mr. Sharpe, and as a former comptroller general, he brings a high level of pragmatism to his engagements with the group and its quest for data.

“We’re a government that prides itself on informed decision making, but we have no data on a people that are sort of crying out for supports and addressing issues,” Mr. Sharpe said. “So, he found that to be something that needed to be addressed.”

And despite Mr. Matthews’ full plate as the coronavirus pandemic hit and the scramble to procure millions of pieces of personal protective equipment began, Mr. Sharpe said he has still been “remarkably available” for the short conversations with the group.

The need for better data prompted FBEC to also seek out its own. It launched a survey in May to dig into Black employees’ experiences with discrimination, harassment, and career progression. The 41-question study closes June 30, and is being completed in collaboration with independent researcher Gerard Etienne. Mr. Sharpe said more than 1,000 responses have already been collected, surpassing their expectations.

In a June 11 follow-up response to questions, Mr. Duclos’ office reiterated his commitment to better data collection and analysis. The Treasury Board Secretariat and Mr. Duclos “work with partners such as the Association of Professional Executives to lead shifts in mindsets and behaviours as the public service embraces diversity and inclusion,” his office said.

…Earlier this year, FBEC was among a community working with the Canadian Human Rights Commission about its high dismissal rate for race-based complaints. “We’ve since been following up with Canadian Human Rights Commission, directly with the chief commissioner and her people, around ways in which we can use disaggregated race-based data and other processes to address the fact that the system’s not working for Black and racialized people,” Mr. Sharpe said.

FBEC has also been working with the Canada School of Public Service, following up after Mr. Sharpe publicly made comments in February noting that the school has a mandate to educate, but produces white managers and staff who perpetuate anti-Black racism.

They are now developing programming that includes the Black experience, the same way that programming already includes lived experience of other equity-seeking groups—as well as having discussions with executive trainers about including education about anti-Black racism.

“That’s the institutional stuff we’re talking about that departments can do and put in place that would help, we think, over the long term that would make us … more visible and put us in a position where we’re actually a legitimate part of the public service,” Mr. Sharpe said.